An Interview with Pat Crocker

This interview was conducted as part of Everything Herbal’s ‘Herbal Elders’ series. This series seeks to honour and explore the unique contributions of longstanding members of the herbal medicine community in Canada, as well as abroad.

This interview was conducted with Nick Faunus, Penelope Beaudrow and Victor Cirone.

Everything Herbal: Tell us about yourself, and how you first became interested in working with healing foods and herbs.

Pat: I have been fascinated with food since I was young. We didn’t have Cola or candy of any kind in our house, so I learned at a very early age that if I wanted to feed my sweet tooth I had to learn to bake. So I baked everything! That is where my fascination with food started. I got focused on food when I went to university and knew that I was going to teach food and nutrition. After graduating, I taught high school students how to cook and then I segued into business, taking a leave of absence from teaching, to which I never went back. I freelanced for a variety of food companies, tested new products, wrote their copy, provided recipes. I then became interested in the area of food photography, and studied styling for food photography. Eventually I met up with another home economist who was freelancing and we realized that there was a better way than what the existing advertising agencies had going on, so we formed a public relations agency that focused specifically on food. We launched new products for companies like Heinz and Campbell’s soup; the conglomeration of Kraft foods didn’t exist at the time. Now there are only really one or two major food companies, but this is when they were all rather small.

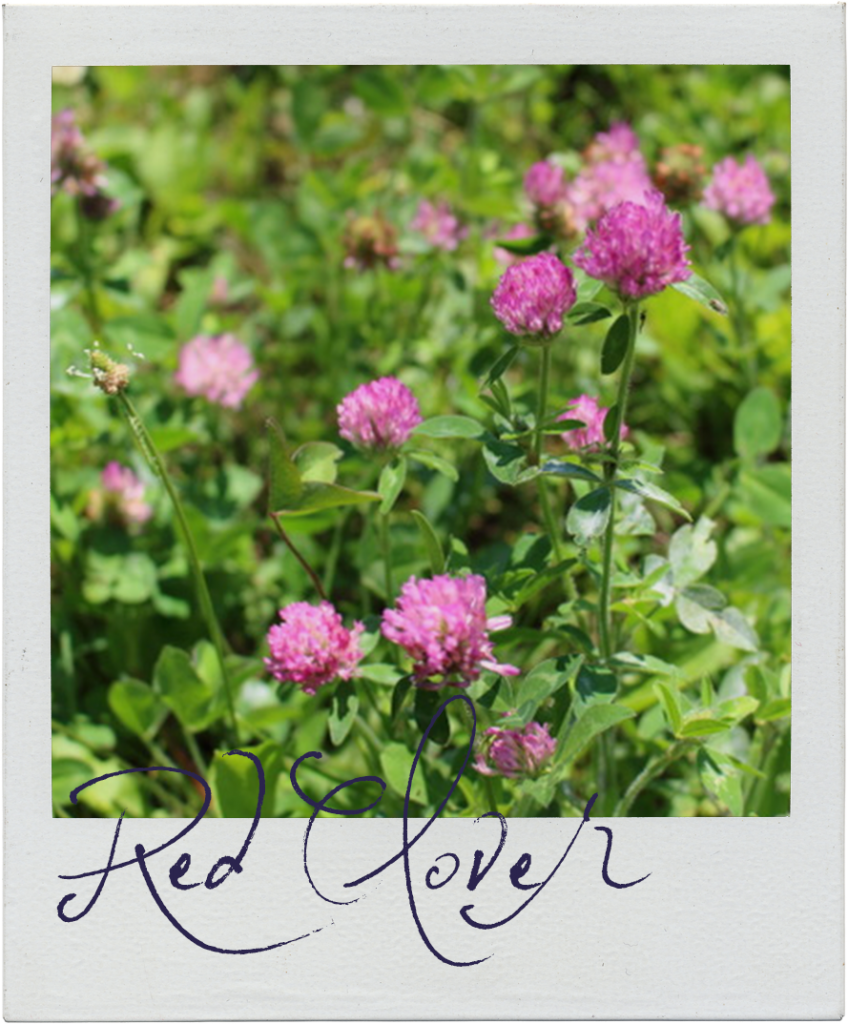

When I met my husband and had a child, we moved to the country and I got focused and even more passionate about herbs and how herbs and food can affect healing. I took herbal medicine courses with a lot of great Canadian herbalists and started a little herb garden. We were living in a log cabin at the time, where I planted a herbal teaching garden, to which I invited many teachers. For 5 years we ran herb walks, going into the wild, down to the river. I was just down there the other day and I can’t believe all of the wild herbs that are thriving. Food and healing was always woven into whatever I was doing. Now I am introducing spirituality into my teachings and my writing because it is all coming together in a whole as mind/body/spirit.

Pictured: Pat Crocker harvesting Sweet Grass

“It was and is so important for me to give back and be part of that herb and food community in whatever ways I can.”

Everything Herbal: Can you tell us about your involvement with the Ontario Herbalists Association?

Pat: When we moved to the country I still had a lot of strong bonds and ties to Toronto. I had been a member of the OHA for a long time, when Keith Stelling was putting out ‘The Canadian Journal of Herbalism’. I would provide material pertaining to herbs and food, practical application recipes for the journal. I also worked with John Redden when we were doing the Herb Fair. They were very heady days; when we were down at Ontario Place we would get what would seem like tens of thousands of people coming in. It was huge. Eventually I became the president of the OHA for a couple of years. When I was living in Toronto I was also president of the Ontario Home Economics Association. It was and is so important for me to give back and be part of that herb and food community in whatever ways I can.

Everything Herbal: Those of us who were working in the herbal industry shifted away from the herbal associations because they didn’t really focus on our needs. And today we don’t have a lot of power; we don’t have a lobby of any kind. We have dealings with the government all of the time but there isn’t really a voice to speak for us. Many of the associations relating to industry are there for seemingly cosmetic reasons. There were attempts to develop the professional side of the herbal associations but it never really took off. It all feels like a missed opportunity. How do you feel about these issues?

Pat: Greed got in the way; many people are oriented around the thought: ‘what’s in it for me’ rather than: ‘how can I meaningfully contribute to the industry?’ It is a missed opportunity, but the time might be coming back. We need younger people with energy. It is really a full time job to run an active association of any kind, and it requires money and resources, and a dedicated network of people.

Everything Herbal: What was the long term vision that you and others had when you were involved with the OHA? Are we there now?

Pat: It was so long ago and we weren’t really politicized at that time, except for Conrad Richter who was actively going to Ottawa. When things started to become political, I was in the process of pulling back and moving to the country, coming out of my term in office. When I was president we were focused on the herb fair, which helped to raise the profile of herbal medicine in Ontario. We had vendors coming from all over. I think it is time for herbalists to start thinking about launching similar public outreach efforts, to help raise the awareness of herbal medicine amongst the general population.

“That’s the advice I can give to anybody: dedicated, quality time for your work. Use your evenings for dreaming and scheming.”

Everything Herbal: You are the author of some 24 books. How have you been able to maintain your productive/creative life over all of these years? What sort of boundaries do you set for yourself so that you don’t become burnt out? Can you talk to us about the importance of self care practices?

Pat: You have to start with clarifying your intentions. What is it that I need? And how can I help others? These are the two intentions I always start with. Self-care has to include a spiritual component. I started out with a meditation practice but didn’t hit my stride with it. For the last 6 months, every single day, I do two hours of spiritual work with Caroline Myss. She started out as a medical intuitive, and her offerings have been deeply transformative for me. You need to find what works for you. Routine and dedication are important: I have a structure when I am writing, I get up at 6AM and work for two hours, then have breakfast and come back to work at 9. There are no interruptions; my email and phone are off, and I work for 4 more hours, and then I’m done. If you can get 4 hours of dedicated quality time that is all the time you really need to work, to get some good writing done. My energy is high in the mornings and it wanes throughout the day, so I work with it rather than against it. I can leave all of the shopping and cooking and the telephone calls for the afternoon. That’s the advice I can give to anybody: dedicated, quality time for your work. Use your evenings for dreaming and scheming.

Everything Herbal: Tell us about the content of your books for those who are unfamiliar with them. What are you working on now, and how has your writing evolved over the years?

Pat: ‘Riversong’ is the book that came out of my time in the cabin, where all of the herb walks took place. That was the first book, which was a product of serendipity. My husband is an illustrator and he was called down to a meeting in Toronto. There was a new publisher who was just starting out and who had asked my husband to illustrate a children’s book. As chance had it, this publisher was also looking for cookbook authors, and so the door was opened for me. This first book was called ‘Riversong’ because the Saugeen River runs through the 18 acres where our cabin was situated. ‘The Healing Herbs Cookbook’ was my second title, which presented the recipes that I had developed from the herb walks. The concept I had was to actually talk about each herb at the beginning of the book in some detail. That quickly became the format for most of my books: I talk about the herb or the food, give a useful description, talk about the taste and flavour profile, the parts used, and the healing properties. ‘The Herbalist’s Kitchen’ came out in 2020, and it has even more of a focus on herbs than any of my previous books do. There I go into a lot of information on each herb. By the time I wrote ‘The Herbalist’s Kitchen’ I had been travelling and visiting many gardens, photographing herbs and herb gardens, and these photos made their way into the book. Now what I would like to do is focus in on the spiritual aspect of eating, and how discipline in eating can help you with discipline in your spiritual practice, or vice versa. The two go together. This is the area that I would like to serve now.

Pictured: Riversong Suites’ Waterfall

Let your food be your medicine…

Everything Herbal: We always come back to Hippocrates: let your food be your medicine. Life, food and spirit are inextricably connected, and there are so many traditions globally which emphasize the importance that our dietary choices have to our spiritual development, both individually and collectively. Fasting also has major spiritual significance for many. Fasting is a cleansing process, physical and emotions toxins can come to the surface during a fast, and having to face what has been buried is, in a way, a kind of shamanic practice.

Pat: The book that I am working on now starts by describing a 42 day way of eating that acts as a fast that serves to break old habits. My husband and I did it last year and it took me off thyroid drugs and high blood pressure drugs. My husband had a kind of itchy rash that looked like rosacea, it was starting to cover his whole body, and that is now gone too. I’ve also seen this fast help greatly with arthritis. This book will describe this fasting process in detail, which is basically no meat, dairy, no added oils in cooking, basically just fruit, vegetables, nuts and seeds. When it is done properly it is amazing. The discipline you get from doing that strengthens the discipline you need for spiritual practice, whether it is meditation or whatever form your practice takes. The two strengthen each other.

Everything Herbal: Food and lifestyle considerations have always been a part of spirituality. We can look to the intersection of Yoga and Ayurveda as a very clear example. Many people who are involved in yoga today have forgotten about this, as yoga has become a glorified fitness system. But the fact that Yoga and Ayurveda are sister sciences is starting to come into focus, as many people who have been engaged in yoga as an athletic practice are starting to realize that something is missing from what they are doing. Many ancient traditions respect and embody what you are describing, but the intricacies have been lost because of how things have been marketed and sold to people.

Pat: There is a lot of discussion about epigenetics in today’s food and nutrition world, concerning how our genes are affected by our thoughts, and how this controls our form. The connection between bad food and our negative thought forms is becoming clear to many. Sugars and additives, artificial chemicals and fillers in particular, actually block us from being able to discern truth, from being able to discern right from wrong. The toxins in our foods lock us into a viscous circle, and generate strong desires, cravings, and even a need for more and more bad food. When we are trapped in this way, it becomes difficult if not impossible for us to realize and become clear with our intentions, to learn to think for ourselves and step into our own power. What and how we eat has so much to do with this.

“Science is now catching up to what many of our spiritual traditions have been saying for thousands of years now.”

Everything Herbal: As we now know, the human body has an enteric nervous system, a network of nerves, neurons and neurotransmitters which extends along the entire digestive tract; basically, a second brain housed in the gut.

Pat: This is why people have always said ‘I just feel it in my gut.’ Intuitively, we’ve known this for countless generations. Science is now catching up to what many of our spiritual traditions have been saying for thousands of years now.

Everything Herbal: What are some important lessons that you think herbal elders should convey to the current generation of herbalists that are doing their training and just starting to practice?

Pat: We know where we have been, we need to look forward to where we are going. We are moving towards community, towards global cooperation. We are just now as a species understanding that what we do to one we do to the whole. We all breathe together. My advice to younger herbalists is to think about how they fit in to the emerging pattern of the global community, and what their role is when it comes to serving that larger sense of a cooperative and sustainable future. Herbalists are uniquely poised to understand this concept, it is inherent in the work that we do. We get this message of interdependence because we are so connected to nature. The herbalists who are coming up into the world now need to carry this torch a little further.

Pictured: Pat putting together a wildcrafted salad with assorted flowers and herbs.

“Much of the work that I do involves stepping into the Wise Woman archetype…”

Everything Herbal: Can you tell us more about your vision of how herbal medicine fits into planetary ecology?

Pat: If we look at the world today from an archetypal perspective, one thing that clearly stands out is that we are experiencing global pandemic. It is not a coincidence that this pandemic affects our respiratory system. What are we doing as human beings? We are cutting down the lungs of the planet. We are slashing and burning the lungs of the Earth. To me, it is as blatant as the noses on our faces that we are now having to face our collective karma. What we do now is going to affect us and our collective future in so many profound ways. We really don’t have a lot of time to get things sorted. My vision is that we are moving from Homo sapiens to Homo luminous. To get there we’ve got to raise our consciousness from the physical, nuclear weaponry level to the level of regenerative archetypes, which we must learn how to step into and embody. Much of the work that I do involves stepping into the Wise Woman archetype, in an effort to help raise the consciousness of those around me. Herbalists can lead the charge in this direction, towards really making the connection between what we do in our own households, in our neighbourhoods, in our towns and cities – and how this affects the whole.

Everything Herbal: We need to address longstanding patterns of human behaviour, and this pandemic is a vital turning point. There are no coincidences. The pandemic is a portal.

Pat: The pandemic gave many of us in the Western world the time and space to reflect, we were forced to stop what we were doing. We were given time to devote to our spiritual practices, to reflect on what we were doing personally, it was time to disrupt and call into question our old and outdated habits and modes of thinking.

Everything Herbal: There are so many young people today who are plagued with crippling anxiety, and the pandemic has served to shine a light on this too.

Pat: Many people have been anxious their whole lives and they didn’t know it. Anxiety can manifest as weird behaviour and unusual decision making patterns. I am starting to realize that millennials, people born 20 – 40 years ago, were born with an open, intuitive energy system. They absorbed all of the energy that their parents were carrying. I never did that, I was in my own little world. What my parents were doing didn’t so greatly affect me. But every little nuance in my life affected my daughter, for example. We need to recalibrate and figure out how to move from being 5 sensory to multi sensory human beings. That is where we are going, and it is an uphill learning curve. Younger generations have come into the world with their energy systems open, and this is one of the main reasons behind the epidemic of anxiety that many young people are living out from today. The younger generation need more tools to recognize this situation, and have to learn to navigate it in such a way that leads to a regenerative future.

“We have to find a way to live in harmony”

Everything Herbal: Anxiety is often rooted in uncertainty and fear. And we live in an environment where everything is uncertain. The toxic environment poisoned food that we were discussing earlier is the prefect breeding ground for an epidemic of anxiety.

Pat: When we entered the nuclear age, that changed absolutely everything. Civilization has now come to a point where we can destroy ourselves. We can’t run away from that. We can’t get away. There is nothing we can create that will change this fact. We have to find a way to live in harmony and restore the planet before we blow ourselves up.

Everything Herbal: We need to be better people, don’t we.

Pat: Yes we do.

Everything Herbal: Coming back to the Wise Woman archetype, one of the things that we are seeing a lot of today in the herbal medicine world is the hyper-sexualization of women’s bodies as a means of generating attention and selling products and services. What are your thoughts on this phenomenon?

Pat: There is a deep incongruence that comes through in the situation you’ve just described. Culturally we are still teaching that women are sexual objects, advertising and cultural production is still stuck in that paradigm. There are many generations of accumulated religious and cultural guilt that we have been brought up in and that we are still holding on to. We exist in a legacy of the oppression of women and women’s sexuality, and this legacy goes back thousands of years. Until those images, until this whole cultural messaging system changes, it is likely that we are still going to have young women growing up thinking that the only way that they can hold any kind of power is to sexualize themselves.

Everything Herbal: It is important to emphasize the notion of the image; images have deep unconscious resonance patterns that they inflict upon us when we are exposed to them. The digital imaginary has only deepened our collective repressed fantasy life; collective repression is now being orchestrated on a massive scale through a regime of unwholesome, unlawful images. People are searching for meaning in a seemingly nihilistic world, and outwardly projected, programmed images are what is immediately available to them. But true meaning comes from inner pictures, from images that have their source in the soul.

Pat: That is one of our primary tasks going forward, learning to understand and harness our true power, which comes from within.

To learn more about Pat and her work, visit her online at: www.patcrocker.com

–

Photos provided by Serena Mor

Cannabis: Medicine or Poison?

An Exploration from the Perspectives of Traditional Systems of Healing

With the legalization of cannabis in Canada, we are seeing a growing public acceptance of this herb, an enormously expanding “cannabis industry”, and a variety of claims being made about its medical efficacy and utility. There are many well-documented traditional medical uses of cannabis, going back many hundreds of years, along with a growing body of contemporary scientific evidence supporting its various medicinal virtues. Yet many of the contemporary claims made about cannabis – branded as a miracle drug – are driven by the desire to sell products or simply as means of justifying one’s indulgences and addictions. In what follows, we will explore cannabis from the perspective of traditional systems of healing and consider some of the less acknowledged and discussed adverse reactions and disturbances that result particularly from its chronic use.

Sola dosis facit venenum; “All things are poison, and nothing is without poison; the dosage alone makes it so a thing is not a poison.” All medical practitioners, irrespective of their methodology or tradition, should carefully consider this phrase, attributed to the alchemist Paracelsus (1493 – 1541). In our era of one-size fits all medicine, Paracelsus’ insight into the difference between a medicinal and poisonous action of a substance being in the dose is not so widely understood. It is however quite germane to our discussion of cannabis, and rife with implications for understanding the nature of the substance. Paracelsus’ dictum leads us to the primary realization that the benefits or dangers of any substance – be it a food, herbal supplement, pharmaceutical drug, etc. – are entirely dependent upon the level and degree of an individual’s susceptibility to that substance. This phrase also asks us to question the range of effects that a particular substance can have, leading us to explore the nature and definition of a poison effect. Poisoning is not equivalent to a lethal dose, though it can lead there. Poisoning, we can say, is when an individual’s capacity for feeling and function has been disturbed.

Every Day Use

It is with chronic, daily cannabis use that we can often observe a very clear disturbance of an individual’s capacity for feeling and function, though the user may not always be able to perceive such an alteration. Many cannabis users have become convinced that their daily habit is what allows them to function, to be more creative, more emotionally balanced, more spiritual, less anxious, better able to relax and to sleep, etc. More often than not, those who make these emphatic claims have fallen under the spell of cannabis, and are no longer able to see beyond its alluring veil.1 As homeopath Colin Griffith explains: “what these users fail to see is that whatever effects their bodies manifest do not belong to them but to the drug. They are instruments on which the chemical drug is playing tunes. The effects are no more theirs than they would be if they took antibiotics for a tooth abscess.”2

In response to a patient’s inability to live her life without the use of cannabis, the natural medicine practitioner should ask: why is it that you are not able to function optimally in the first place? What are the underlying maintaining causes of your emotional imbalances and disturbances? Why do you have such difficulty relaxing and falling asleep? In such cases cannabis use may only be serving to suppress or cover over an underlying constitutional issue that needs to be properly addressed. And when we suppress a problem, rather than working to resolve or cure it, this may result in its temporary disappearance, but it certainly has not gone away. Suppression takes a surface manifestation of a disease and drives it to a deeper, more vital region of the organism, where it can create more chronic, intractable and debilitating illness.

An Ancient Medicine

Cannabis has a long history of use as a medicine. The Persian physician Avicenna (980 – 1037), who no doubt was familiar with cannabis strains much different than those that are available today, wrote of the use of cannabis for the alleviation of severe headache as well as treatment for degenerative bone and joint diseases, inflammation of the eyes, general edema, infectious wounds, gout, and uterine pain. However, he also pointed out that cannabis produces dryness that is “desiccating” (disrupting and deranging the vital fluids/fluid metabolism of the body). There are many clear signs that cannabis is warming, including increased appetite, red eyes, dry mouth and tongue, rapid heart rate and elevated blood pressure. As cannabis is excessively warming, it can result in a disturbance of the warmth activity of the organism, especially with regards to the metabolism. Chilly, sluggish and deficient digestive processes can often be observed in chronic cannabis users. The above mentioned symptoms are especially pronounced when it comes to the intensely psychoactive strains of cannabis that are grown today.

From the perspective of Traditional Chinese Medicine, it can be said that chronic use of cannabis can result in injuries to the Yin, damage to the Jing, and disturbance of the Shen. The primary constituent that causes such disturbances is THC. This is because, as herbalist Paul Bergner has remarked, “THC binds to the encocannabinoid receptors (CBD does not), and because it is many times more powerful than the endocannibinoids, the receptors drop in number and also become less responsive to maintain homeostasis.”3 Daily cannabis consumption often leads to gradually increasing dosage and frequency of use, clearly suggesting that tolerance and adaptation can develop quickly and easily.

Herbalist Todd Caldecott provides us with a useful explanation of cannabis from the perspective of the Ayurvedic tradition:

“Cannabis displays some of the properties of a poison, in that it spreads very quickly (vyavahi) and loosens (vikashi) the tissues. Through its subtle (sukhma) and penetrating (tikshna) qualities, it actually expands the space between all the cells of the body, opening up the channels (srotamasi). This is the reason for feeling high, and why it is consumed by sadhus and babas [who, unlike the average person, have been trained to focus their mind through contemplative practices]. It creates a subtle feeling experience that connects our experience to akasha (ether), the element of pervasiveness. So it opens and elevates consciousness, but not in an evolutionary way – just as a transient and limited experience of infinite space.”4

It is because cannabis serves to create space and allows for movement in the body that it can exhibit pain-relieving properties. It is for the same reason that cannabis can be utilized in some cancer treatment protocols (cancer is an uncontrolled proliferation of cells, when the tissue of our body can no longer maintain or identify its own boundaries. Hence, cancer is a disease that is very much related to ‘space’).

Recreational Use

While the chronic use of cannabis presents more pronounced dangers than occasional use does, infrequent or recreational consumption can still cause deep-seated disturbances on the level of body, mind and spirit – again, if that degree of individual susceptibility is there in a person. The use of cannabis “to relax”, for example, can easily become an addiction in the same way that others become addicted to drugs like diazepam to go to sleep at night or to “manage” (suppress) their anxiety symptoms. Such addiction is an often unconsciously motivated attempt to circumvent having to develop strategies and lifestyle changes that can lead to true understanding of the root causes of one’s issues. Without such an understanding, true resolution or cure is not possible.

The Physical Effects

Cannabis regularly results in a disturbance of the bladder, prostate, and sexual functioning in men. Cannabis can act as a potent aphrodisiac in the short term, but will usually lead to a lessening of erotic desire and even to impotence in some. Habitual use of cannabis results in a lowered white blood cell count, suggesting its negative affects on immune function. The homeopathic materia medica and provings of cannabis reveal that the adverse immune response that cannabis precipitates increases an individual’s susceptibility to bacterial respiratory infections as well as non-specific urethral infections, gonorrhoea, and chlamydia (homeopathic cannabis is an especially well known remedy in the treatment of gonorrhoea, and is indicated for genital discharges with burning pains and discomfort more generally).

The homeopathic materia medica of cannabis also reveals a strong affinity for disturbances of the thinking processes, with pronounced disorientation and a sense of disconnection accompanied by a free floating anxiety. The patient requiring homeopathic cannabis may often make mistakes in reading and writing and may generally have poor comprehension, tend to be forgetful and can become easily confused. While there can be difficulty concentrating, there can also be rapid thoughts and a pronounced tendency to theorize and draw far-fetched connections. Patients requiring homoeopathically potentized cannabis may report a sensation of the head being separated from the rest of the body (a symptom that says much about the state of being too much in one’s head, which cannabis in its crude form easily leads to. When this state progresses to severe pathology we can see, for example, paranoia and depersonalization. While cannabis users may give the appearance of being mellow and laid back, this appearance is often a symptom, as Colin Griffith notes, “of the distance that the cannabis has fostered between the smoker and reality”5). Other notable cannabis symptoms from the homeopathic literature include: sensations of being ungrounded, spaced out, unable to physically support oneself, of the limbs or the whole body feeling so light that it could float away; panic attacks, many fears including the fear of being alone in the dark, of entities, and of insanity. Rajan Sankaran notes that cannabis patients tend to exhibit oversensitivity and the need to “cover up for a feeling of inadequacy…The perceived weakness is actually an inadequacy in facing the threats, dangers and risks of the outside world. The Cannabis person feels unequipped to face them directly and hence observes the world from within the safe confines of a “glass cage.””6

Many of the above mentioned symptoms of chronic cannabis use are further understood when we consider the effects that cannabis has on our neurology. With prolonged use, cannabis disrupts the balance between the thalamus and hypothalamus and the pineal and pituitary glands. The anterior pituitary gland is responsible for the secretion of thyroid stimulating hormone, adrenocorticotrophic hormone, growth hormone, follicle stimulating hormone, luteinising hormone, and prolactin. We have a growing body of evidence suggesting that cannabis use results in significantly lowered levels of thyroid stimulating hormone. The hormones released by the thalamus and hypothalamus serve to regulate our flight and fight response, our appetite, thirst, and eliminatory processes. Negative modifications to these bodily functions are typically present after long-term use – at which point cannabis addiction tends to have already set in.

Ongoing pharmacological research on THC strongly suggests that it has marked affects on neuronal signaling and development, and researchers are beginning to explore how THC exposures during pregnancy could lead to adverse long-term changes in the neuronal development of babies and infants.7 Other research has drawn links between mother’s who smoke cannabis during pregnancy and an increase in the risk of their children developing leukemia and a variety of other serious birth defects. There have been further studies suggesting an increased risk of cancer of the esophagus and stomach with chronic cannabis use.

In Conclusion…

Cannabis is a complex herb, and one that should be carefully understood by those who use it. While public perception presents us with a marketable (and hugely profitable) image of cannabis, the reality of cannabis is more nuanced, multifaceted and complex than we are led to believe.

Footnotes:

1 From the perspective of the doctrine of signatures, the usually 5-leaved cannabis plant closely resembles a hand. This hand, it can be said, reaches for and makes an effort to grab hold of the cannabis user, who is rendered incapable of extricating herself from cannabis’ intoxicating embrace.

2 Colin Griffith, ‘The Companion to Homeopathy’ pg. 169.

3 Paul Bergner, unpublished writing.

4 Todd Caldecott, unpublished writing.

5 Griffith, ibid, pg. 168.

6 Rajan Sankaran, ‘The Soul of Remedies’, pg. 39.

7 See, for example, Kimberly S. Grant et al. ‘Cannabis Use during Pregnancy: Pharmacokinetics and Effects on Child Development.’

Photos provided by Serena Mor

A Herbal Apprentice's Journey: Season's Turn

December, 2021.

“Look at this one.” My mother says to me, extending her arms toward me to display her treasure. A bouquet of gemstones, iridescent and gleaming even in the scant light of the overcast day.

“Look at THIS one!” I respond, placing another treasure into her bouquet.

“Wow.”

We stood under the layers of clouds, rotating fresh corn in our hands and marveled at each new pattern and colour. One by one, revealing a story beneath the husks. I wasn’t certain of the kind of corn we had planted. It was an unmarked seed package that bestowed upon us what seemed like a million colours. A million gemstones. Rich in the palette of autumn.

We sunk digging forks into the soil in search of our next treasure; potatoes. This summer was my first time growing them. The relationship I gained while doing so was surprising. Witnessing their blooming was utterly charming. Witnessing their decay was similar. Trusting that they would continue to grow under their little mounds, out of sight.

We ate lots of early potatoes as the summer waned. I watched my partner one morning from the window as he stepped out to the garden in the fragile light. Barefoot and squatting in the greenery, choosing one plant that may be willing to offer our breakfast. Clearing away a little mulch and soil to retrieve just enough for our meal. Stopping for a moment of thanks before bringing them in to clean in the sink.

Now I stood in an empty garden bed, a bucket of potatoes unearthed. Autumn feels like that to me; an abundance and an emptiness. A direct example of reciprocity. An opportunity to recognize how we collaborate with the earth in such a clear and tangible way. Where once there was soil, now has returned to soil, and, miraculously, I carry this bucket of potatoes.

It was spring when I began my apprenticeship work with Penelope. While we spent time in the sanctuary, our conversations would whirl with personal anecdotes and philosophy. For some time, death was our muse. For days, nearly everything we did seemed to shine with the beauty of death and, in effect, start a passionate conversation. How death is a portal, a ceremony, an honour. If we can imagine that Winter may represent death, Autumn would be our chariot to take us there. There’s something mournful about the slowness of the Autumn months.

Come Winter, a season of inward incubation. Maybe a return to the womb, to emerge in spring reincarnated. That’s how I like to see winter, though it may be daunting. I always know that after months of a dark, deep freeze, I begin to daydream longingly of touching plants, swimming in water, feeling the sun. And yet I trust, as I trusted the potatoes to grow out of sight, that come spring the world would transform into lushness again. Truly a miracle, for the earth itself to be resurrected.

Socrates said “death itself may be the greatest of all human blessings”. While his friends wept for him in his dying he asked them to not cry, for he was at last meeting the greatest mystery of all.

What mystery are you meeting this winter?

I read a wonderful passage written by Italo Calvino in his book The Complete Cosmicomics. I’d like to leave you with it and hope that you may savour it. I do think that winter is our time of implosion.

“To explode or to implode -- said Qfwfq -- that is the question: whether 'tis nobler in the mind to expand one's energies in space without restraint, or to crush them into a dense inner concentration and, by ingesting, cherish them. To steal away, to vanish; no more; to hold within oneself every gleam, every ray, deny oneself every vent, suffocating in the depths of the soul the conflicts that so idly trouble it, give them their quietus; to hide oneself, to obliterate oneself: perchance to reawaken elsewhere, changed.

Changed... In what way changed? And the question, to explode or to implode: would one have to face it again? Absorbed by the vortex of this galaxy, does one pop up again in other times and other firmaments? Here sink away in cold silence, there express oneself in fiery shrieks of another tongue? Here soak up good and evil like a sponge in the shadow, there gush forth like a dazzling jet, to spray and spend and lose oneself. To what end then would the cycle repeat itself? I really don't know, I don't want to know, I don't want to think about it: here, now, my choice is made: I shall implode, as if this centripetal plunge might forever save me from doubt and error, from the time of ephemeral change, from the slippery descent of before and after, bring me to a time of stability, still and smooth, enable me to achieve the one condition that is homogeneous and compact and definitive. You explode, if that's more to your taste, shoot yourselves all around in endless darts, be prodigal, spendthrift, reckless: I shall implode, collapse inside the abyss of myself, towards my buried centre, infinitely. “

Photos provided by Serena Mor

A Herbal Apprentice's Journey: Discovering Self Trust

November, 2021.

There are a few notable reasons why I first began studying herbal healing, and alternative healing modalities. The first, unsurprisingly, would be my interest in the natural world. I was raised in rural Ontario, and for half of that time, my family was off-grid. As a child in that time, I would have nothing but moss, loon calls and rare wolf sightings to delight my dreams. My brother would build zip-lines from tree to tree. I have a cherished photo from a disposable camera of myself proudly displaying a bow and arrow I’d fashioned for myself out of a branch, some twine, and a bit of time with a pocket knife. The world was full, and so alive in those days. I would spend an entire afternoon squatting on the Canadian shield, in the middle of a quiet lake, studying the language of the moss formations that had dried in the sun. Each molecule of water, sky and earth sang to me.

As I grew older, my fascination with moss and water and dreaming about what the fish and the birds had to say began to dwindle. Elders and peers of mine had fascinations with other material things. Such things were framed as more important. I still longed for deep conversations with the soil and rocks. I still longed to play among them, while they held me up and I called out for the fairies to reveal themselves, wielding my wooden dagger and a pocket full of stones.

I was a sort of weird kid in a small town. I struggled to find a community that truly resonated with me. In my adolescence, I found yoga. I listened to The Grateful Dead and wrote songs about the earth that I didn't yet understand. These were practices that felt grounding to me. A way to connect with that inner child that found wonder in all. I took psychedelics and marveled at the magnificence of trees. One evening, I lay in the soil and told my friends that I knew deep in my soul, that I was a stone. Part of the Canadian Shield.

I often find lots of humour in the revelations I’ve had while sitting with psychedelics. I think the most amusing part is how simple the lessons are. How it sometimes takes a great journey to understand that we are one, that you were correct all along in your childhood wonder, that magic exists and that god is nature and nature is everything. The simplicity of knowing.

I am a seeker of knowledge. You may have guessed by now. All of my life I have attempted to outfit myself with a metaphorical tool belt, equipped with things to allow me to understand the great mysteries of life. One of the most pivotal moments for me - with the guidance of psychedelics - was realizing how much I needed to trust myself.

Trusting myself began my journey in herbal medicine. It was what I turned to when I realized that I had given so much of my autonomy to doctors. I do trust doctors and I believe that they are deserving of trust - what made me uncomfortable was realizing that I had never trusted myself, or my intuition, when it came to my health. I had given doctors complete authority over my body and health. I would often go to a doctor, tell them my symptoms, and I would be met with an answer similar to, “it’s all in your head”, or leave with a prescription for something that I would know nothing about. It was frustrating, yet I felt as though there was no way out of that system.

It feels like it has taken me a long time to arrive here. Knowing that my body is always healing, perpetually. When we treat the body for something, we are simply encouraging the body to heal. Whether it is traditional plant medicine, or modern allopathic medicine, the sentiment remains the same.

Your body is healing every moment of the day. Your body wants to be healthy, to exist in the world with ease and in harmony. Our greatest tool in health is to trust this fact: the body knows how to heal itself. From this perspective, it isn’t exactly plants that are healing us. It is our own selves doing the work of healing. The herbs become a supporting role, a reminder, a tool to help with the work.. But the actual “ work” is done by the body. Herbalists don’t heal you, herbs don’t heal you, it is your own body that is in collaboration with all of these things.

I’ve heard allopathic medicine described aptly as “Heroic Medicine”, which makes a lot of sense when we learn the history of its development in war. In herbal medicine, there is not one hero. Herbal medicine is “Wholing Medicine”, in which one works in collaboration with plants, spirit, knowledge and an understanding and trust in the complexities of healing. May our healing be as dynamic as this life and this world. May our healing be a collaboration with the healing of all, and for all generations of the past and future.

Photos provided by Serena Mor

From Biophilia to Biophobia

The Love and Distrust of Herbal Medicine

The process of modernization can be described as the transformation of biophilia (the love of and communion with nature) into biophobia (the fear and distrust of nature). Industrialization and the commoditization of everyday life are only some of the more recent forces that cemented this change, which in reality reaches much further back into Ancient Greece and Rome, as can be see in the hegemonic Christianization of Pagan culture, or the decline of Greco-Roman polytheism.

The transformation from biophilia into biophobia should be of interest and concern for herbalists and practitioners of natural medicine generally, as it is the underpinning of the ideological foundation of the ideas that many today harbor towards non-pharmaceutical based healing traditions and practices. These contemporary attitudes which espouse, for example, the notion that plant based healing is dangerous, untrustworthy, ineffective, unscientific, etc., are part of a much larger fear of the wild that stems from a generations long process of alienation from nature. Herbalist and ethnobotanist Wolf-Dieter Storl discusses how the forest, once held to be a magical and paradisiacal realm of great mystery and grace, gradually became a place of fear and trepidation. Wild plants that once provided sustenance in the form of food and medicine to one’s ancestors came to be regarded as potential poisons that should not even be touched, let alone ingested. This distrust and abhorrence of nature is the essence of biophobia. Biophobia is a treacherous trap for the body, mind, soul and spirit that has been laid down alongside and in lock step with the deployment of the global machinery of industrial society and the shifts in human perception and spiritual life that lead to it.

Speaking to the legacy of biophobia in the Western world, Dieter Storl writes:

“Western people are scared of rabid foxes, and they are afraid to eat wild raspberries or blueberries – after all, they might be contaminated with fox tapeworm eggs. And there are ticks, which can cause Lyme disease and encephalitis if they bite you. The best solution is never to go into the forest! (Or you can do what many do when they go hiking, and march through the forest as if through enemy territory). When considered soberly, however, the fear of the forest reveals itself to be mere hysteria. The likelihood of catching rabies or tapeworm in the woods is less than the chance of being hit by a truck. The fear of the forest is the fear of one’s own soul, of the “evil witch,” of the shadows of one’s own personality.1”

The fear of the soul is often tied up with the repression of bodily feeling and somatization (any unconscious and nonvolitional process where physical symptoms are produced as a consequence of one’s ill-founded psycho-emotional attitudes and disposition). It is through the soul that we are capable of producing bonds of intimacy between self and world. The last century in particular has seen massive increases in the technical proficiency of machine technologies, but this has come at the cost of understanding the importance of nurturing the capacity to sense, feel into, and thereby be transformed by the natural world. When this capacity is diminished or lost, nature then becomes something that exists outside the boundaries of the self, something that indeed is thought to threaten the stable foundation and identity of the self. The felt sense of immediate experience, the communion with other-than-human life, is substituted for an abstract realm of thought governed by the separation and division of subject and object, self and other, inner experience and outer nature… When the awareness of “external” nature is repressed, then so too is our own bodily awareness.

Of Repression

There are few places where the legacy of this repression is reflected more strongly than in the transformation of agricultural work and attitudes towards the land. The great Goddess guided early farmers and agriculturalists through her gifts of vision, inspiration and dreams.2 It was understood by our ancestors not only that the Goddess stands as our protectress, but also that she sees, hears, feels, and mourns, that she is part and parcel of every aspect of our experience as living, breathing beings on planet Earth. The benevolence of the Goddess is what makes the soil fertile, and her guidance is what allowed agricultural societies to emerge and prosper. As Dieter Storl continues:

“Agriculture progressed in a continuous dialogue with her [Goddess Nature]. Plowing and tilling the soil were considered an act of love; impregnating Mother Earth was the religion, and those who impregnated her were the worshippers. In fact, the word cultivate originally meant nothing more than service to the gods, honor, sacrifice, and nurturing.”3

A far cry from the Round Up drenched, monocropped fields of contemporary agricultural production.

Of Forgetting

The forgetting of the benevolence of the Goddess should be thought of in relation to the demonization of the Pagan Gods, Ancient Greece and Rome more generally. This was a development that, as noted above, was ushered into being through the proliferation and enforcement of domineering strains of Christianity. We can see this quite clearly in the gradually shifting attitudes and attributes bestowed upon Greek and Roman tutelary deities (i.e. guardian, patron, and protector spirits). Faunus, to take but one example, was the ancient Roman God of the forest, plains and fields, the guide and protector of shepherds, huntsmen and all inhabitants of the countryside. He was a great companion of the nymphs, the feminine nature deities who populated and cared for the myriad creatures of the Earth and presided over the diverse phenomena of nature, from springs and waterfalls to clouds, trees, caverns and meadows. Faunus played a great role in the fertility cults of the ancients, and was honored as an important overseer of both agricultural production and the health of the forest, as well as (in his form or aspect as the God Innus) the primal embodiment of human sexuality and procreative powers.

Faunus was depicted as a voluptuous and sensual being and, in some traditions where he was held to be synonymous with the Greek God Pan, as the inventor of the flute, whose music charmed wild animals and appeased the spirits of nature. Faunus was one of the favourite and most honored Gods of the Romans, as Pan was for the Greeks. Innumerable shrines and monuments in honour of Faunus/Pan were placed throughout the countryside and in wild places. And it was perhaps for this very reason, that of the immense popularity of Faunus and of Pan, that Christian theologians felt it incumbent upon themselves to cast these most beloved of Gods into disrepute, striking fear in the hearts of their worshipers and devotes with the threat of the eternal damnation of the soul.4

Of Demons and Angels

In the Greek translation of the Old Testament, the Septuagint, ‘good’ spirits are described as angels (ángelos, ἄγγελος “messenger”) and ‘evil’ spirits as demons (daimónia, δαιμόνια). This dichotomy of good and evil was foreign to the Greek notion of a daimon, which simply meant “godlike”, “power” or “fate”. Daimons were originally held to be benevolent and benign deities who oversaw the rightful and just fulfillment of fate and destiny, not as less than divine or malicious spirits who corrupted human nature and condemned souls to hell.

Faunus and Pan thus became nightmare demons. Where they were once the bestower of prophetic dreams, they became the harbinger of fearful illusions and malefic hallucinations. Where they once stood as one of the principal life-givers and protectors of the forest, they became the embodiment of the ‘dark’ side of nature, of that which needed to be kept at bay. The Greeks came to see those who suffered from epilepsy, for example, as being possessed by Pan (for the Greeks and Romans alike, epilepsy and madness were very closely related; epilepsy was thought to be the precursor to madness).5 The Romans ascribed a series of afflictions to an incubus by the name of Faunus ficarius, including “emaciation, violent unrest at night, and agonizing pains.”6

Of Written Word

Textual tradition, and the power and authority that came with it, also played a great role in the transformation of medicine from an ancestral, folk tradition of healing to something that was overseen and governed by the men of letters (the state licensed Doctors). In his book The Social Transformation of American Medicine, Paul Starr describes the folk healing traditions of the early American settlers, that the Doctors were later to chastise and condemn, in the following way:

“The family, as the center of social and economic life in early American society, was the natural locus of most care of the sick. Women were expected to deal with illness in the home and to keep a stock of remedies on hand; in the fall, they put away medicinal herbs as they stored preserves. Care of the sick was part of the domestic economy for which the wife assumed responsibility. She would call on networks of kin and community for advice and assistance when illness struck, in worrisome cases perhaps bringing in an older woman who had a reputation for skill with the sick.7“

Many of these women, who carried out the traditions of their ancestors in supporting and upholding the life and health of their communities, were to be persecuted as witches. The folk medicine that they worked to maintain came to be held up as heresy.

The state licensed doctors were as ignorant of the virtues of traditional healing systems as were the Inquisitor’s of the marvelous virtues of the Pagan gods that they sought to demonize. The doctors were able to remove the popular healers with great urgency by falsely casting them as witches who perpetuated evil and misfortune, just as the Inquisitors were able to divorce the Pagans from their animistic immersion in the world through the introduction of the dichotomy of good and evil and the threat of eternal damnation.8

Of Understanding

To understand the state of traditional medicine and the folk healing arts today, and why such traditions have been cast in such a negative light, it is important to understand the conquest of nature that began far back in the ancient world. Such conquest served to gradually divorce humankind from the experience of the living world in its pure immediacy. But the repressed always returns, and the living memory of health and harmony is again today finding its rightful place in the hearts of many.

Footnotes:

1 Wolf-Dieter Storl. Witchcraft Medicine. Vermont: Inner Traditions, 2003. Pg. 2-3.

2 When one looks, for example, to one of the earliest known sculptural representations of the face, the approximately 25,000 year old figure of The Venus of Brassempouy, it becomes abundantly clear how deeply rooted in the ancient past is the worship and devotion to the Goddess as the bestower and protector of life.

3 Ibid, pg. 3.

4 Not all Christians, however, were opposed to Pagan ideals. There was in fact a tradition of associating Faunus/Pan with Christ himself. Both Faunus/Pan and Christ were shepherds. Neither were entirely divine, Jesus Christ being simultaneously divine and human and Faunus/Pan was likewise a God as well as an earthly being, in part due to his very close and intimate association with humankind. Given this fusion of human/divine characteristics in both the figures of Faunus/Pan and Jesus Christ, some later Christian poets, including most notably John Milton, described Faunus/Pan as a pagan prefiguration of Jesus Christ. Such prefigurations were generated by poets who lived mostly after the Reformation period, and not by priests, bishops, or popes, or those were behind the bloody conquests and inquisitions of the ancient world.

5 Marten Stol. Epilepsy in Babylonia. Groningen: STYX Publications, 1993. Pg. 49.

6 Wilhelm Heinrich Roscher. Pan and the Nightmare. New York: Spring Publications, 1990. Pg. 65.

7 Paul Starr. The Social Transformation of American Medicine. New York: Basic Books, 1982. Pg. 32.

8 For more on this, one can consult the work of the the American anarchist historian and activist Fredy Perlman, who describes the conquest of the doctors in the following vivid language: “The so-called witches, heiresses to the informally transmitted knowledge of herbs and illnesses, are known to be healers, whereas the Doctors, notoriously ignorant of all this lore, are intent on establishing a State-licensed monopoly over illness so as to police the sick. The Doctors will eventually appropriate some of the herbal knowledge of the exterminated witches, but the healing will always be incidental to the policing. They will persecute illnesses even if they have to turn human beings to vegetables or cut them to shreds… Leviathan’s licensed agents even move to expropriate radical visionaries of their memory of human freedom, kinship and community. State-licensed visionaries, Masters and Doctors of Letters, Philosophy and Metaphysics, send their tentacles probing among the last traces of memory’s remembered humanity. The lettered Doctors appropriate the witches’ healing arts.” Fredy Perlman. Against His-Story, Against Leviathan!. Detroit: Black and Red, 1983. Pg. 238.

Photos by Serena Mor

The Story of the Haiti Naturopathic Clinic: An Interview with Julia Graves

Emergency Medicine and Disaster Relief in Haiti

Welcome to an interview with Julia Graves! This interview was conducted by Victor Cirone with photos used with permission from Julia.

This interview was conducted on May 27th, 2021, before the assassination of Haitian president Jovenel Moïse, and before the recent, devastating earthquake of August 18th. Julia is currently coordinating fundraising efforts for the earthquake victims and to help support the vital work that is carried out by the disaster relief clinic that is the focus of this interview. To find out more about how you can help, and for updates on the current situation in Haiti, please see the clinic website and subscribe to their newsletter: haitinaturalclinic.org

Victor: What can you tell us about the trajectory of your life and work, and specifically how you got to where you are working in Haiti?

Julia: The moment of us starting the clinic in Haiti is, in a way, the culmination of my life up until that point. I was raised by an herbalist mother and an orthopedic surgeon father, so I’ve worked between the paradigms of conventional medicine and plant healing. Then I trained four years of medical school and as a psychotherapist, and I always continued to work with plants and natural healing. I had at that point, when the great earthquake struck Haiti, at least 30 years of experience of working with herbs, flower essences, aromatherapy, and homeopathy. Because it was my partner’s [Jacquelin Jinpa Guiteau] home, and his father got injured in the earthquake, it became very compelling to go and help. If you remember, it was an underwater earthquake, so the epicenter was off the coast, under the ocean, about 3km out – Jinpa’s parents’ home was exactly 3km on the shore. His father fell and injured his shoulder, but we couldn’t send him any help, and we couldn’t go there because all flights had been stopped. As soon as the first airplanes were allowed back into Haiti, he went to just see the situation and said, ‘if I go I would like to help people who are in need of medical care, could you put something together for me as a first aid kit?’ Which is what I did. 48 hours later he called me and asked if I could join him immediately (I was in France) and bring $10000 in donated cash and two suitcases more full of natural medical supplies. 24 hours later I was in New York to pick up the cash and more than 2 suitcases worth of donated supplies, and in 48 hours I was in Haiti, in the rubble. And that’s how it all started.

I do want to add one thing: all of my experience went into a precise concept of the clinic. I had a very clear idea that homeopathy would be great: it’s tiny, it’s light, you can give one pellet per person, and so with a tiny amount you can treat the masses. If need be, you can succuss more, you can dilute and potentize more. Similarly with essential oils, you can do a lot with very little. Although I’m very much an herbalist, I was very clear that trying to stuff dried herbs into your suitcase, or bottles and bottles of tinctures is just not ideal for an emergency situation. So, based on my background, I clearly favored homeopathics and essential oils and that was the bulk of what I brought initially.

V: Most of the audience who will be reading this interview will have more of a background in herbal medicine than they will in homeopathy. At least in North America, there is still a fairly strong divide between herbal medicine and homeopathy. There are some herbalists that I’ve encountered who have even expressed suspicion or outright disdain for homeopathy, claiming that there’s no way it has any real efficacy, that it lacks scientific legitimacy, etc. Can you tell us more about the protocols that are used in the clinic and why homeopathy is so important to the work you do there, beyond how easy it is to transport homeopathic remedies and how cost effective they are?

J: Let me first talk a little about why I brought essential oils. First of all, we as herbalists quite rightfully assume that we can use the essential oil of chamomile in a similar way to chamomile tea or tincture. It is very easy to make that transition when you are faced with an emergency situation where you can’t put a lot into your suitcase, and so, take a variety of essential oils. The other thing is that essential oils are highly antiseptic – they kill everything, as it were: antibacterial, antiviral, antifungal, antiparasitic. Most essential oils are the first three, and some also end up being antiparasitic. When we reached Haiti, the streets were so cracked open, everything had fallen to pieces, and the stench in the air of the rotting bodies was just unfathomable. In such a situation, you want something that is very, very ‘anti-everything.’ On top of that, to purify the air from germs, you want to use essential oils. You can spritz them, you can leave them out, and you can literally disinfect the air around you in that way. It was very good for us as healers to be in a situation like that where we could handle substances that served to protect us from disease. We still got horrific diarrhea, but there wasn’t even anything close to clean water available at that point.

For me, I can understand that most herbalists cannot understand homeopathy. There’s an element of mystery to it. You can’t understand how it can possibly work. I trained very young in homeopathy, when I was 19. By the time I went to Haiti I had tons of experience using homeopathy in emergency situations. I had lived in India for 3 years where I trained at the Tibetan monastery that is next to the Dalai Lama’s palace in Dharamshala, and there is no medical care for the little boy monks there. So I was treating a lot of these boy monks and people in India who were in very desperate situations, including lots of animals and lots of babies, so I knew for sure that you don’t have to believe in homeopathy for it to work. I had treated people who can’t speak because they are babies, I treated animals, people who can’t speak the same language as me, who have no understanding of what I’m putting into their mouths, and I had seen incredible results in very poor hygiene type of environments. I had complete confidence, I had my baptism by fire, what the horse rider experiences when they fall off the horse for the first time – I had already been through that. At the point I came to Haiti nobody could have talked me into the idea that homeopathy is not effective. And I was already very experienced treating myself and others, so for me it was just a no brainer, especially when it comes to vulneraries, injury remedies, or things for acute and superficial issues such as disease from dirty water – diarrhea and vomiting – I had tons of experience treating that in India.

To take another common scenario we encountered in Haiti: being sick as a consequence of sleeping outside in the cold. When we got to Haiti it was March, the earthquake was in January, so everybody had been sleeping in the streets in February when it is quite cold, and we have this wonderful remedy in homeopathy called Aconite, which is also used in Chinese medicine to warm people up, for diseases from cold. There are wonderful homeopathic remedies from the Artemesia genus of plants, which are also used in herbalism, for the treatment of worms and parasites. In underdeveloped countries virtually all children have worms. We could discuss many other common scenarios and the relevance of homeopathic medicine in dealing with them. Based on my previous experience, I already knew what I was going to need and want. We had anticipated injuries, coughs and colds and the usual stuff such as malaria and yellow fever; but we hadn’t anticipated the mind-blowing amount of vaginal infections, which had nothing to do with the earthquake per se, but with poor hygiene and dirty water. And for that we then had to work out a treatment protocol.

Lastly, just to add one more reason explaining why the homeopathic approach was so great in this context, especially in the initial years, was to treat street children: You cannot give a homeless three year old who lives in the street anything herbal – a bottle will be lost almost immediately, they have zero access to potable water, let alone a fire or tea kettle so herbal teas are out, etc. I was incredibly grateful to have a reliable and powerful method where I could give the child one single dose right into their mouth and know it could cure whatever ill was at hand (worms, influenza, head trauma), with the higher potencies’ action lasting for weeks and months.1

V: I remember that in one of your previous newsletters, you talked about a traditional Haitian practitioner, a herbalist and bonesetter, and I remember that you said in that piece that the Haitian people were somewhat skeptical of working with him, that they didn’t believe that he had the healing abilities that he did. Can you talk about the attitude of the Haitian people when it comes to disease and healing generally, and about traditional Haitian healing practices in particular?

J: We literally had to start the clinic by putting a table and four chairs out. There was Jinpa on one side being one of the doctors, me on the other side being the other doctor, with a second chair for each of the patients. We immediately had 300 or more people a day, between 300 and 500. The most we could treat on a given day was 500. There was a lot of skepticism. People were desperate because there was no medical help at all available to them; you have to understand that the medical system in Haiti is such that when people can’t pay, there are zero medical services available to them. We were in the city of Port-au-Prince because the epicenter hit there. There are no wild plants there. In the Haitian countryside there is still traditional herbal medicine available. People were very skeptical of us because first of all they had very bad experiences with large organizations such as the Red Cross. There are two main things we heard over and over again: the first was that people didn’t want to stand in line and wait to be treated because, as they said very suspiciously, ‘are you going to force vaccinate us?’ and we explained that we don’t even have syringes here, everything is natural, we use plants. And the reaction then was ‘oh, then I’ll stay in line.’ So there was tremendous skepticism towards being forced vaccinated, which is part of the International Red Cross’ way of doing things, apparently.

Then they were very surprised that we actually spoke their language rather than them not being able to communicate with us at all. They liked that. The second thing that made them very gun shy, quite literally at first, was that the other organizations, even Doctors Without Boarders, usually have a building that is guarded by soldiers with machine guns. People are reluctant. They were literally looking around and scoping out the place, wondering ‘where are the soldiers with machine guns? Oh they don’t even have protection, now I feel safer waiting in line.’ The third thing that made them gun shy was that there was a practice, a very widespread practice, of dumping expired pharmaceuticals into Haiti which has been stopped since then. The government made this practice illegal and now checks expiration dates on pharmaceutical drugs coming into the country. There has also been a kind of undercover testing of non-licensed drugs in Haiti. People who were coming to the clinic kept saying ‘we get things that are expired, we go to the hospital, they give us an injection, and we get so sick.’ We heard that over and over again. So all of that was overcome the moment we said ‘no, no we only use plants and we don’t have injections’ and whatever we gave them also looked nothing like a pharmaceutical drug. That was one kind of very strong caution and mistrust we had to overcome.

And then there was the caution and mistrust that they harbored in regards to their own tradition. Of course because they have been brainwashed by modern media, education, and all of that, the herbs grandma uses are not good. We tried to role model to them that healing with plants is okay. We knew that the husband of one of the women known to Jinpa’s family was a traditional herbalist, midwife and bonesetter, all wrapped into one. We asked him to come in and do his work. We checked it out and he was really quite knowledgeable and had a lot of very helpful things that he was able to do that we couldn’t. For example, he knew exactly what kind of a poultice to use on children no older than 2 years old in order to heal inguinal hernias. We didn’t have anything like that, where you could just take a few drops of a medicine and the hernia is gone. And he was able to touch a pregnant woman’s belly and could check if she was carrying one or two babies, if they were in the right position, if everything was generally okay with the baby, the position of the placenta, if the woman needed pelvic adjustment – he could do those things that we weren’t trained for from within the traditional context and it helped people have confidence in their own traditions again. They really liked the treatment and we often overheard them when they were leaving saying ‘oh yeah I have a person like that in my neighborhood, maybe I could go see them.’ We tried to really not be like the Red Cross, which has come in from the outside totally detached from the local culture, from traditional Haitian medical thinking and understanding, from their language use and using products that come from elsewhere and were threatening. It was very important that we create an interface with the people, their culture, their language, their healing traditions. That was very much our aim.

V: Do you have cases that stand out that you’d like to share?

J: One of our cases that I love to talk about is that of a 2-month-old baby boy who was brought in to us who had been declared to be dying of yellow fever. He had been born to a 15 year old teenage mother and the bonesetter explained to us that girls like that will not bond with their baby if they see that the baby is sick, as a protection mechanism they then drop the baby, they emotionally disengage, because they want to save themselves the heartbreak from having their firstborn die. The mother had literally wandered off doing other things and left the baby in the tent camp and the warden of the camp, Marie-Lucie who is now working for the clinic, brought in the baby for treatment. She explained that the baby is dying, that the family had scraped together their last bit of money to bring him to the hospital, that the doctor diagnosed yellow fever and explained that it would cost a million so to speak for medical treatment, which they didn’t have. What happens in Haiti in such a situation is that the doctors will say ‘go on, take the baby home it will die.’

The baby was brought to us at that point and he seemed to be in a very dire condition, hanging limbs, the eyeballs turned up, and I was there with this very difficult situation, in a screaming environment with hundreds of people standing in line, tasked with being given 5 minutes to diagnose and heal a dying newborn. One of the things we use very much in the clinic as a diagnostic tool is Chinese pulse diagnosis because then you don’t need language. One of our questions for people coming to work at the clinic is: what do you know to diagnose without needing language, because you won’t be able to speak Creole or French, most likely. So, anyone doing Chinese medicine will know how hard it is to take a good pulse with a newborn. I used a technique where I took his pulse – you take the pulse with the fingertip of just one finger and it was extremely wiry, a very typical high fever/heat pulse, and I had by that time noticed that I could get really good pulse readings on newborn babies, because there were so many, by just putting the vial with the homeopathic remedy in their other hand. Because they have this reflex of holding onto everything, they just grab the vial. When I put the Aconite in his hand the pulse went down, the heat pulse signs were seriously going down. I gave him one dose of Aconite 200C, which is a very, very classical high fever remedy and within a very short time, something like a minute or two, his flapping hands came back up, the whole tonus came back to his body and – bing! – he opened his eyes. I gave the lady who had brought him a tiny bottle containing a few drops of lemon essential oil and asked that she do some sponge baths to help open his pores and to help cool his body.

We had also asked the bonesetter to come and see what he would say and he had a completely different approach. He felt the baby’s skull bones and he diagnosed his skull bones of being stuck from hard labour and he did something that we would consider a craniosacral adjustment of the skull and then he said the baby needed a paste of castor oil and ground nutmeg applied to the central fontanella, which is what we did. Marie-Lucie brought him back the next day and he was well on his way to recovery. I like to give that story because it is a wonderful example when it comes to situations of extreme healing, how we use the modalities and co-treat with our Western way and the Haitian way.

V: What is it like to see so many patients in a day? In the context that most herbalists are familiar with and work in we have this idea that when you see someone you need 2 hours, that there must be detailed case taking and analysis, and so on. What is it like when you don’t have nearly close to that amount of time and may not even be able to communicate with your patients through language?

J: First of all I want to put this into context. We figured out very fast that anybody who was too intellectual couldn’t function in such an environment as a healer. If you ask yourself too many questions you won’t be able to function there and you have to make a lot of tough decisions before you even begin. Such as: there are things you are not going to treat, we didn’t do shortsightedness, diabetes, caries, and advanced chronic disease – which is not so prevalent in the first place because the population we were working with, the poor people in the ghettos, is what I like to consider a virgin population by and large. They had never had pharmaceutical drugs, vaccinations, operations, or anything else – they were just people who had never been medically treated, and they respond marvelously. They have what I would just call for now more superficial acute diseases and they respond very, very well. We are here to do emergency medicine. That was our focus going in; it was simply not possible for us to focus on treating chronic diseases.

That’s already the shift you have to decide on when you go into a disaster situation, to say we are doing emergency medicine. Since then the clinic has evolved because we have been there for a long time now and we do work on things such as very big difficulties in pregnancy, handicapped children, diabetes, breast cancer and other things like that. But at that time we were doing emergency medicine exclusively. We individualize, but you can’t individualize too much. There is something that I knew from Chinese medicine, which is the art of getting to the point in 3 questions. I told everybody you have to perfect that. You have to very quickly have the three questions that eliminate everything down to 2 or 3 remedies – then differentiate between them and you’re there so that you can on average treat a person in 5 to 10 minutes. I had to see 150 people a day, I was so exhausted that I couldn’t function anymore and we had not by any estimation seen everyone in line. The line looked to be the same length at 7AM as it did late in the afternoon when we finished, because we couldn’t go on. The other thing is the environmental context, with this brutal, damp, tropical heat and you’re being eaten by mosquitos top to bottom the entire time you’re sitting there. So for Jinpa and me, what we did was we just allowed ourselves to be in some kind of a trance or autopilot state using intuition. This is not the kind of intuition where I’m intuiting something that I have never heard about or have no experience with. I’m talking about intuition that comes out of a lot of knowledge and experience. For me, it was actually a really nice experience to be in a situation where I can’t intellectually think; I don’t have the time, everyone around me is screaming, I’m scratching so much I’m close to fainting, we were very hungry, we couldn’t eat, it was very dirty, it was extremely unsafe to eat, we couldn’t eat until the whole work day was over, there was no water… It was beautiful to see that when you have to, you can operate like that as a healer; I believe you have to be trained though. I don’t know if that could work if you had no prior knowledge of working in such an environment.

(Robinson takes Marie Lucie to treat a person struggling to breathe)

(Robinson takes Marie Lucie to treat a person struggling to breathe)

V: What can you tell us about the COVID situation in Haiti? You mentioned in the last newsletter that it doesn’t seem to be affecting the population very much at all. (As of May 27th, 2021)

J: COVID has done very little in Haiti up to now; they’ve started a large clinical trial to find out why that is the case. There are a lot of ideas that have not been verified, such as that there are very few enclosed spaces – the vast majority of the population essentially lives outdoors, the houses don’t have glass enclosing the windows and the doors are always open and wind is always blowing through the houses. Also, it has been discussed that half of the population is younger than 18, as well as other factors relating to Haiti being an underdeveloped country. From my own point of view, it is very well worth considering that they are so unspoiled by civilization in many ways, that the population tends not to suffer from deep chronic diseases. The kind of conditions that we are always pointing to as making a person vulnerable to COVID, don’t exist for the vast majority of people living in Haiti. This is a sugar producing country, even the poor kids do eat sugar, but they are so hungry so often in between that they do not have diabetes. No chance.

In the pre-COVID era, it was established basic epidemiology that you do not start to vaccinate while an epidemic is ongoing, because you’re essentially going to create mutation pressure on the virus. In this case, it is remarkable and frightening to me that now that vaccination has started in Haiti, although most people don’t want to get vaccinated as they are very suspicious against vaccinations, that now suddenly COVID is becoming a problem. There are rumors that now that the Brazilian variant has arrived it mostly hits the gut, so people get diarrhea like symptoms for 2 or 3 days and then are dead. I think it’s way too early to say much about it, so we are also right now quickly looking at how to adapt our protocol. Up to now we’ve had really amazing results [treating symptoms] just using essential oils of peppermint and eucalyptus, which are antiviral, antifebrile and bronchodilating, so I think peppermint is still a good idea for a virus affecting the gut, but we may have to rethink things. I’m just waiting to get past the rumor stage, so we can differentiate between what we are hearing about the symptom picture and what is actually going on. We need to get things substantiated, because the political situation is completely corrupt and malfunctioning at this point. People are not even sure that what is now being said about COVID in Haiti is not just a series of rumors that the government has put out in order to manipulate people in some way – the political situation has deteriorated to such an extent.