Fenugreek: Materia Medica

Trigonella foenum-graecum

Fenugreek is an herb with a long and esteemed history both in medicine and the culinary arts. Some authors suggest that fenugreek originated in India and North Africa, while others suggest that it is indigenous to the eastern Mediterranean region. One of the earliest recorded uses of Fenugreek comes to us by way of Egypt, where it was used in incense making as well as in the process of embalming mummies. Fenugreek, as the name suggests, was widely utilized by the ancient Greeks, for whom it was a staple food. The name foenum-graecum, which literally translates as ‘Greek hay’, refers to the practice of mixing fenugreek with inferior quality hay in order to increase and enhance its scent.

Nutritional and Medicinal Value

As part of its nutritional profile, fenugreek contains considerable amounts of vitamin B and phosphorous compounds (e.g. lecithin), making it a culinary herb with a special affinity for the nervous system (lecithin is a mixture of neutral lipids and phospholipids, which are important constituents of the central nervous system and play a role in promoting and maintaining the health of the brain’s functional pathways). Fenugreek is often added to curries, where it serves to aid and promote healthy digestive function but also helps to prevent gas, bloating, cramping, indigestion, heartburn, and acid reflux in susceptible individuals. Fenugreek contains considerable amounts of iron, and may be well employed in some cases of iron-deficiency anemia: fenugreek helps the body in the process of blood formation. Continuing with the nutritional properties of the herb, Dorothy Hall remarks: “As it also manufactures in its growth vitamin A and a vegetable-form of vitamin D, it is supportive of liver function too, and protective of all mucous-lined body organs. There is much sulphur present; and also choline, and support for cholesterol metabolism” (Hall: 1988, 159). Fenugreek is an herb to consider when dealing with a hypo-functioning liver. In Ayurvedic medicine, fenugreek is recognized as “a good herbal food for convalescence and debility, particularly that of the nervous, respiratory and reproductive systems” (Frawley & Lad: 2001, 190)

Concerning the use of fenugreek as a medicinal herb, Hall provides us with the following overview:

“Its properties may best be summed up as supportive of liver function, protective to mucous- linings all through the body, and giving renewed nervous energy. There is a fourth benefit, however, and one which is becoming more and more necessary today: Fenugreek clears and promotes the drainage of the body by the lymphatic system. As lymphatic vessels and lymph- fluid movement are essential parts of our immune system, Fenugreek may become a valuable plant for the future.” (Hall: 1988, 159)

Fenugreek is likely the most frequently employed herbal galactagogue, meaning that it helps to promote the production of breast milk. It is also widely used in the treatment of diabetes type 1 and 2, where it helps to increase the body’s tolerance for carbohydrates, reduces blood sugar and total LDL cholesterol levels. Fenugreek can be used by men who experience seminal debility (i.e. issues with the quality and quantity of sperm), as well as for erectile dysfunction and low libido (fenugreek contains furostanolic saponins, which have been linked to increased testosterone production). Fenugreek is a lung tonic and has its place in the treatment of asthmatic complaints, as well as lung and sinus congestion. A paste made from fenugreek seeds can be used topically for ailments such as boils, ulcers, burns, and poorly healing sores (Frawley & Lad: 2001, 191). Other traditional indications include: tuberculosis, gout, and generalized body pain.

On the level of herbal energetics, fenugreek is: bitter, pungent, sweet/heating/pungent. It affects the plasma, blood, marrow, nerve and reproductive tissues and has an affinity for the digestive, respiratory, urinary, and reproductive systems (Frawley & Lad: 2001, 191). Fenugreek is a stimulant, especially for a slow-draining lymphatic system and where there are issues with edema and fluid retention. Fenugreek possesses diaphoretic and mild diuretic actions. It also possesses tonic, expectorant, rejuvenative, and aphrodisiac properties.

Works Cited:

Hall, Dorothy. Dorothy Hall’s Herbal Medicine. Melbourne: Lothian Publishing Company, 1988.

Frawley, David & Lad, Vasant. The Yoga of Herbs. Wisconsin: Lotus Press, 2001.

—-

Image Credits:

Krzysztof Ziarnek, Kenraiz: Mildly colour edited version of their original Fenugreek image.

Coffee: The Good the Bad and the Ugly

An Historic Global Enterprise

Coffee is one of the most ubiquitous and widely consumed beverages in the world, second only to water. The already extraordinary demand for coffee only seems to be increasing; global coffee production reached 175.35 million 60-kilogram bags as of 2020/2021, increasing from about 165 million 60-kilogram bags in 2019/2020.

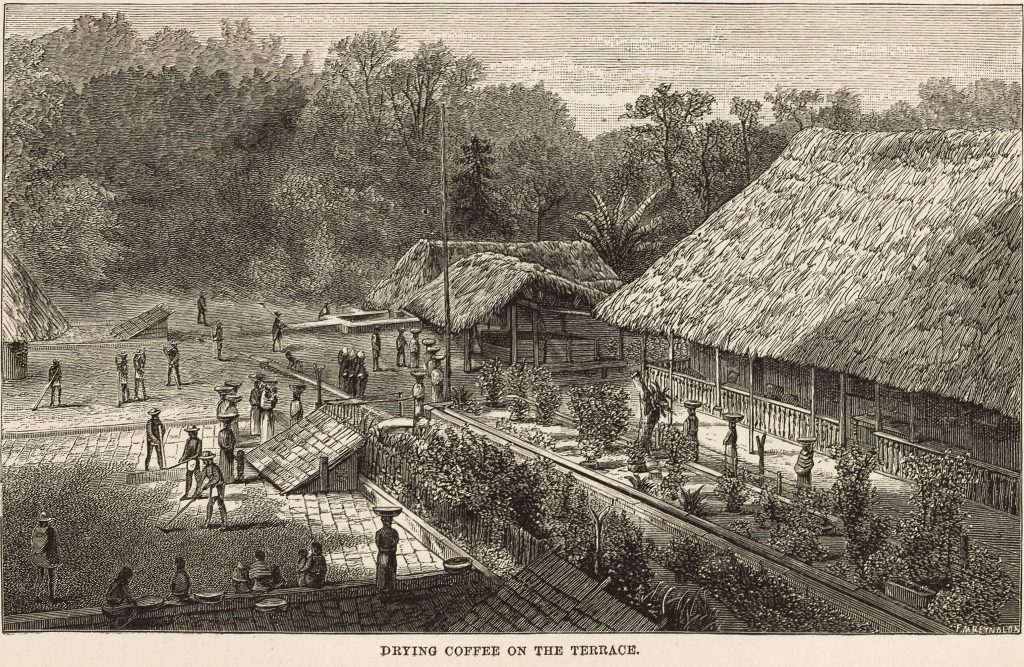

Coffee drinking, and the knowledge of the coffee tree as a medicinal substance, dates back to at least the mid 15th century, where we find our first credible historical evidence pertaining to its use in the accounts of Yemini author Ahmed al-Ghaffar. The coffee tree was most likely introduced into Yemen by way of trade routes with Ethiopia from across the Red Sea. Thus, given that the coffee tree was being traded and exported from Africa, it is highly unlikely that its medicinal, recreational, and social values were only realized in the 15th century, in a country where the tree itself was not native. The use of coffee almost certainly reaches back much further than the 15th century, though specifics concerning its initial discovery by the peoples of the African continent and its use in their traditional systems of medicine and culture remain obscure.

When it comes to the earliest detailed historical records concerning the use of coffee, we can look to the work of Harvard historian Cemal Kafadar, where it is revealed that the social significance of coffee in Islamic society was established by way of its use in Sufi religious rituals:

“To turn to the early history of coffee and coffeehouses, more specifically, there must have been many instances when coffee was consumed as a plant found in the natural environment of Ethiopia and Yemen, but the earliest users who regularized its consumption as a social beverage, to the best of our knowledge, were Sufis in Yemen at the turn of the fifteenth century. Evidently, they discovered that coffee gave them a certain nimbleness of the mind, which they were keen on cultivating during their night-time vigils and symposia. Thus started the long history of the appreciation of coffee as a companion to mental exercise and conviviality, particularly when one wished to stretch or manipulate the biological and social clock.”1

The Start of The Coffee House Phenomenon

It is from this point onward that coffee houses started to appear across Arabia and gradually, over the next three centuries, throughout the rest of the world. The historical significance of the coffee house is inextricably bound up with the historical significance of coffee itself; the coffee house has always served as a kind of public institution and cultural hub through which all manner of information – from the common and mundane to the revolutionary and political – was shared and disseminated amongst the population. Even today, in a world increasingly characterized by digital identities and disembodied forms of social engagement, the coffee house still serves as a place of respite, where people can turn for a semblance of embodied interpersonal interaction and exchange in an evermore alienating and depersonalizing world.

Coffee’s appearance in Europe (especially England and Germany) in the late 17th century coincided with the discovery that clocks could be controlled by harmonic oscillators. This was followed in the 18th century by a series of technological discoveries and breakthrough inventions that lead to increasingly precise clocks, and hence to a heretofore unimaginable regimentation of time itself. Is it a mere coincidence that coffee – utilized by so many for the purposes of maintaining attention and increasing stamina – came to Europe just as machine production and the Industrial Revolution, with the inhuman demands it placed on workers, led to a decline in hand production and the artisanal trades of the past? From the perspective of cultural history, coffee has a dual identity; as a tool for social conviviality and the free flow and exchange of ideas (exemplified by the institution of the coffee house), as well as a crucial ingredient in the engineering of the industrial worker, allowing for the kind of over-stimulation that is required to meet the demands of the fast paced, mechanized world of industrial society. The hegemony of standardized clock time, and the counting of seconds, minutes and hours as measures of productivity and profitability, violated the natural diurnal rhythms that human beings had always used to orient their lives. The question remains as to the extent to which coffee played a role in one of the biggest cultural shifts in recorded history.

Historical Religion and Politics

The opinion of the medical profession with respect to coffee has been divided throughout history. Coffee is exemplary when it comes to demonstrating the degree to which medical opinion can be deeply influenced and shaped by cultural and political trends and assumptions. Indeed, the medical, socio-political and religious views of coffee were at times inextricably bound up with each other, making it next to impossible to disentangle one from the other. Where does religious belief end and medical “fact” begin? We can explore this issue by taking a closer at the early history of coffee in the Islamic world, and the changing tide of opinion with respect to the most influential and powerful drink in the world, next to water itself.

In contrast to the view that the introduction of coffee into liturgical practice was a great blessing in that it allowed worshipers to better execute their devotions to God, other religious scholars argued that coffee should be outlawed insofar as it had never been mentioned in the Quran. Many of these scholars were also concerned about what they perceived to be the deleterious health consequences of coffee consumption. But this controversy is even further muddied when we stop to consider the political climate of the time. While some commentators argue that the various attempts to outlaw coffee in the Islamic world were a consequence of religious and medical opinion, the truth is more likely that coffee (and the social revolution spurred by the birth of the coffee house) was perceived as a political threat.

“Between the early 16th and late 18th centuries, a host of religious influencers and secular leaders, many but hardly all in the Ottoman Empire, took a crack at suppressing the black brew. Few of them did so because they thought coffee’s mild mind-altering effects meant it was an objectionable narcotic (a common assumption). Instead most, including Murad IV [the Ottoman sultan who issued a ban on coffee in 1633], seemed to believe that coffee shops could erode social norms, encourage dangerous thoughts or speech, and even directly foment seditious plots.”2

In what is perhaps an unexpected twist, our brief survey of the cultural and political history of coffee has revealed the extent to which many of our deeply held assumptions, sometimes taken as objective fact, in actuality rest upon a socio-political and theological underpinning of opinion and currents of dogmatic belief which colour our perception, of which we may be mostly or even totally oblivious.

PART II: Coffee as Medicine, Coffee as Poison

What is the difference between a food and a medicine? In his essay from 1803 titled ‘On the Effects of Coffee’, Samuel Hahnemann (the founder of homeopathy) set out to clarify this distinction and to warn of the deleterious effects of the unchecked consumption of medicinal substances, taking coffee as a paradigmatic example. Hahnemann writes:

“Medicinal things are substances that do not nourish, but alter the healthy condition of the body; any alteration, however, in the healthy state of the body constitutes a kind of abnormal, morbid condition. Coffee is a purely medicinal substance. All medicines have, in strong doses, a noxious action on the sensations of the healthy individual. No one ever smoked tobacco for the first time in his life without disgust; no healthy person ever drank unsugared black coffee for the first time in his life with gusto — a hint given by nature to shun the first occasion for transgressing the laws of health, and not to trample so frivolously under our feet the warning instinct implanted in us for the preservation of our life.”3

A medicine is a substance that serves to alter the state of health, whereas a food is a substance that serves to provide nourishment. When medicines are taken in excess, or when they are not properly indicated for an individual person, they can produce an abnormal or even pathological condition. Medicines can preserve life and maintain health, though they can also derange the state of health and take life away when they are given without the requisite attention or care. Food substances can likewise produce states of disease if they are eaten to excess, though the deleterious effects of foods generally take a much longer time to manifest when compared to the stronger power of medicinal substances to affect deep seated changes on the level of constitutional vitality.

While in 1803 Hahnemann condemned the use of coffee, going to so far as to argue that its unchecked consumption was the origin of many of the chronic diseases that plagued humanity, he later toned down his opinion, having developed a much more sophisticated theory of the origins of chronic diseases by way of the concept of the miasms (the 18th century precursor to our contemporary theories of epigenetics, and one of the philosophical foundations of homeopathic medical practice to this day). Nevertheless, Hahnemann was right to emphasize the extent to which medicinal substances, when treated as foods and consumed injudiciously, can exert profound effects on the state of health. This is especially true if conditions of heightened susceptibility to a given substance are at play in an individual’s constitution (think here of the example of severe allergic reactions to substances that to most people are extremely benign). Human response to coffee and to caffeine varies widely, and like any assessment of a medicinal substance, individual response patterns must always be given a higher regard than overly generalized, universal theories and pronouncements. The difference between a medicine and a poison is ultimately in the dose, and the effect of the dose is always weighed in relation to the individual to whom it is administered.

The Hahnemann of 1803 represents one extreme when it comes to thinking about coffee as medicine. A look at the medical literature on coffee, from from the 15th century to the present day, is full of contradictory and opposing points of view. Coffee was for centuries listed in the pharmacological and medical literature that herbal and Eclectic physicians relied upon, such as the Codex Medicus. Coffee remained classified as a medicinal substance in materia medica and pharmacopoeias until the twentieth century, when the use of natural medicinal substances was largely supplanted by the products of the petrochemical drug industry. Maria Letícia Galluzzi Bizzo et al. recount some of the claims made about coffee in the medical traditions of the West, emphasizing and siding with the view of coffee as a universal elixir of health (the poplar opposite of Hahnemann’s position):

“As a panacea, coffee has been prescribed as infusions, capsules, potions, or injections against a vast spectrum of diseases— from hernias to rheumatism, from colds to bronchitis. In the first half of the nineteenth century, medical controversies underlined the therapeutic use of caffeine in chronic conditions such as heart and circulation problems because of difficulties establishing the proper doses and the risk of toxicity to the heart. Nevertheless, the notion that such use would be safe prevailed. Recent research has opened new horizons regarding the use of coffee as a medicine, with discoveries of possible distinct preventive and curative applications of coffee’s substances.”4

The Coffee of Today

The medical opinions of the past are in many ways inadequate when it comes to judging the effects of coffee today. The coffee of the 1800s is not the coffee of the 21st century. Consider, for example, the question of pesticides. Only about 3% of the world’s coffee supply today is produced using organic methods, and we now know that the residues of pesticides found on coffee beans, one of the most pesticide ridden agricultural products in the world, are for the most part not destroyed by the roasting process. Many countries that produce coffee use pesticides that have been banned in North America and Europe over health and safety concerns, and a significant number of the countries which import this coffee do not have maximum residue limits (MRLs) when it comes to the pesticides that are used and can be detected on the harvested coffee beans.

Mold is yet another issue. When not stored in a temperature controlled storage facility, coffee beans are also highly susceptible to developing mold, which comes with its own host of long term adverse health effects. Even roasting techniques have a great bearing on coffee’s potential effects on one’s state of health. One study carried out by the International Association for Food Protection, for example, comes to the following ambiguous conclusion concerning the question of the carcinogenicity of coffee and how this is affected by the roasting process:

“Roasting coffee results in not only the creation of carcinogens such as acrylamide, furan, and poly-cyclic aromatic hydrocarbons but also the elimination of carcinogens in raw coffee beans, such as endotoxins, preservatives, or pesticides, by burning off. However, it has not been determined whether the concentrations of these carcinogens are sufficient to make either light or dark roast coffee more carcinogenic in a living organism.”5

There are a whole host of other socio-economic and political considerations that should be borne in mind with respect to the global coffee industry of the 21st century. Health is not a purely individual consideration; the health of your body and mind are indissociably bound up with the functioning of the larger natural and artificial systems in which you exist. We are unwitting participants in a global system of capitalist exploitation which, through the untiring impulses of profitability and expansion, inevitably leads towards the total degeneration of the natural world and the complete immiseration of its inhabitants. A sober and careful look at coffee and its economic, political, and agricultural ramifications, inevitably alerts us to a confrontation with this reality.

Capitalism, Globalization, and the Politics of Coffee Production:

The pesticide residues found in your average bag of coffee are inconsequential in comparison to the toxicity that third world coffee farmers are exposed to on a daily basis. These farmers, in addition to the dire health consequences of chronic chemical exposure that are an unavoidable part of their work, lead lives that are dictated by the brutal conditions of strenuous labour, physical exploitation and the inter-generational cycles of inescapable poverty, child labour and indentured servitude. Alice Nguyen, in an article written for The Borgen Project (a non-profit organization dedicated to addressing the global issues of poverty and hunger), unflinchingly encapsulates these issues:

“Growing coffee requires intensive manual work such as picking, sorting, pruning, weeding, spraying, fertilizing and transporting products. Plantation workers often toil under intense heat for up to 10 hours a day, and many face debt bondage and serious health risks due to exposure to dangerous agrochemicals. In Guatemala, coffee pickers often receive a daily quota of 45 kilograms just to earn the minimum wage: $3 a day. To meet this minimum demand, parents often pull their children out of school to work with them. This pattern of behavior jeopardizes children’s health and education in underdeveloped rural areas, where they already experience significant barriers and setbacks.”6

Facts like these seem to underlie the importance of Fairtrade and Organic Certification for coffee and related products, which in principle strive to ensure sustainable development, equitable trading conditions, and giving autonomy back to marginalized farmers and agricultural workers. However, consumers in the Western world must not fall into the self-congratulatory trap of thinking themselves morally superior because they are able to afford the often vastly more expensive Organic and Fairtrade Certified products that are simply outside of the economic reach of many. The reality is that, in many instances, the increased profits from organically grown coffee products do not reach the farmers and laborers themselves, but end up lining the pockets of the distributors, who in many regions of the world function in similar ways as do drug cartels.

What is more, there are the significant and rarely discussed pitfalls of introducing organic agricultural techniques to farmers who work on lands that have been treated with chemical pesticides for decades. Such agricultural land will require significant time and effort in order to be rehabilitated such that organic farming can be sustained there. This means that farmers who are already struggling to maintain their operations run the risk of falling even further into economic enslavement if they are coerced into adopting the organic methods that righteous and ecologically minded politicians, consumers, academics and other self proclaimed “experts” in the Western world preach about with moral fervour.

Consider the following story, told by the son of a soybean farmer working in El Toledo, Costa Rica. He recalls a childhood memory of the year his father was convinced by Penn State University professors to adopt organic agricultural techniques, under the promise of increased profitability and the ecological restoration of their farmland:

“The professors convinced my dad to make a wholesale change from conventional soybean farming to organic. They warned him that he might lose up to 15% of his yield, but that this would be offset by a number of factors: He could sell his soybeans for more, as they were organic. His soil would be healthier. He would spend less on chemical inputs, and thus save money. The reality was very different. Instead of losing 15% of our yield, we lost 50%. Instead of spending less money, he spent more: the gas he spent to tractor over the weeds alone outstripped his usual chemical spending.

He ended up taking a job in a factory to avoid bankruptcy. All I remember is that when I was eight, I never saw my dad: he was either weeding the soybeans or at the factory. As soon as that season ended, we went back to chemical farming.”7

Many such stories, pertaining to all manner of farming from all parts of the world, can be found if one cares to look beyond the ‘Certified Organic’ and ‘Fairtrade’ labels that one sees plastered on one’s favourite products lining the local supermarket shelves. From coffee and soybeans to chocolate and Brazil nuts and beyond, the exploitation of labourers and the degeneration of the world’s ecosystems are part and parcel of our contemporary agricultural systems of production, whether conventional or organic. Any consideration of “sustainability” must always be understood within the framework of the global capitalist economic system in which we exist. As the political and cultural theorist Mark Fisher so poignantly put it in his book Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?:

“The relationship between capitalism and eco-disaster is neither coincidental nor accidental: capital’s ‘need of a constantly expanding market’, its ‘growth fetish’, mean that capitalism is by its very nature opposed to any notion of sustainability.”8

The preceding section of this article is not intended to inculcate feelings of guilt, a sentiment which only leads to a place of demoralization and further defeat. Rather, it was written out of an honest assessment of the situation in which we all find ourselves as consumers in a system which, in its vast complexity, far transcends the individual decisions that you and I make on a daily basis. It is only from a place of sober awareness that a genuine desire for a better world can be nurtured and allowed to bear fruit.

And now, with these economic, cultural and political factors in mind, let us turn to consider the detailed effects of coffee from a more purely medical perspective. A well rounded discussion of coffee requires that we adopt a multi-perspective view. Single vision is, after all, what the capitalist system of exploitation itself is based on.

PART III: Coffee’s Medicinal Effects: What Can Reliably Be Said?

Coffee is a nervine stimulant, i.e. an herb that causes excitation and stimulation of the nervous system, specifically by engaging or heightening the activity of the sympathetic nervous system. The most widely known and discussed function of the sympathetic nervous system is the mediation of the neuronal and hormonal stress response pattern known as the fight-or-flight response. The sympathetic nervous system is what allows the body to quickly react and respond to situations of threat and danger, to situations that threaten survival. But the sympathetic nervous system cannot be adequately understood if we look at it as an isolated regulatory or physiological function. The sympathetic nervous system works in concert with the parasympathetic nervous system and together make up what is called the autonomic nervous system. The autonomic nervous system regulates and controls many of the functions of the body’s internal organs. When we consider the interdependence and co-functioning of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, then we can begin to understand that the stress response typically associated with the sympathetic nervous system is one pole or extreme of a greater homeostatic controlling mechanism which oversees the feeling and function of the human organism on many levels.

However, excessive stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system can and does result in undue consequences. Herbalist David Hoffmann explains the action of nervine stimulant herbs, and relates their functions to the excessively heightened states of excitation that characterize the frantic and overwrought patterns of 21st century existence:

“Direct stimulation of nervous tissue is not often needed in our hyperactive modern lives. In most cases, it is more appropriate to stimulate the body’s innate vitality with the help of nervine or bitter tonics. These herbs work to augment bodily harmony, and thus have a much deeper and longer-lasting effect than nervine stimulants. In the 19th century, herbalists placed much more emphasis upon stimulant herbs. It is, perhaps, a sign of our times that the world now supplies us with more than enough stimulation. When direct nervine stimulation is indicated, the best herb to use is Cola acuminata, although Paidlinia cupana, Coffea arahica, Ilex paraguayensis, and Camellia sinensis may also be used. One problem with these commonly used stimulants is their side effects; they are themselves implicated in the development of certain minor psychological problems, such as anxiety and tension. Some of the volatile oil-rich herbs are also valuable stimulants. Some of the best and most common are Rosmarinus officinalis and Mentha piperita.”9

Caffeine is the most widely recognized and studied active ingredient in coffee as well as many other stimulant herbs (such as those listed in the above quotation). But coffee also contains a wide array of other important constituents such as tannins, fixed oils, carbohydrates, and proteins, which should not be forgotten, as coffee, just like all herbs, are irreducible to their component parts. It is through the roasting process that caffeine is liberated from the raw coffee bean. Caffeine produces diuretic and stimulant effects, specifically on the respiratory, cardiovascular and central nervous systems.10 Caffeine is also an analgesic adjuvant, and hence is incorporated into a wide number of proprietary aspirin and acetaminophen preparations.11 Coffee also contains phytoestrogens, which have been subject of a great deal of scientific debate. Phytoestrogens can play a role in addressing symptoms and conditions caused by estrogen deficiency, which may be especially pronounced in premenopausal and post-menopausal women. They are also implicated in memory and learning processes and have been shown to possess anxiolytic effects. The research into the effects of phytoestrogens on human health is still ongoing, and is a fruitful and fascinating area of research. For example, consider the fact that the consumption of beer, bourbon, mescaline, cannabis, and coffee all produce phytoestrogenic effects – the relationship between psychoactivity and phytoestrogenic compounds certainly needs to be more deeply explored!

When it comes to consider possible contraindications and adverse reactions from coffee consumption, we should note that coffee, along with fried and fatty foods, chocolate and alcoholic beverages, can lead to or serve to aggravate LES dysfunction (the lower esophageal sphincter, which links the esophagus and the stomach). Obesity, pregnancy, cigarette smoking, and a structural weakness of the diaphragm known as hiatus hernia can also contribute to a weakening of the LES. If the LES fails to properly close, stomach acid can easily splash up from the stomach into the esophagus, leading to severe acid reflux and heartburn. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (commonly known by the acronym GERD) is associated with a leaking of stomach contents back into the esophagus. When there is a prolonged period of LES dysfunction, this can lead to acid and chemical damage of the esophagus, that is, to GERD.

The consumption of coffee and other caffeine containing substances can also result in headaches. The headaches that are associated with coffee consumption are often related to caffeine dependence, which can lead to significant withdrawal symptoms in some individuals. As Hoffmann writes:

“Caffeine can cause headaches by increasing the body’s expectation for it. When blood levels of caffeine drop, symptoms of withdrawal, including headache, may set in. That’s why some heavy coffee drinkers experience “morning headache” until they have that first cup of coffee. Caffeine headaches are usually experienced as a dull, throbbing pain on both sides of the head. Once the body rids itself of caffeine, the headaches disappear on their own. Such headache sufferers, however, are often unaware that their problem is due to caffeine and will continue to drink coffee, ensuring that the problem will recur.”12

We can look to the homeopathic literature to round out our consideration of the spectrum of effects that coffee can have. In homeopathy, the medicinal effects of a given substance are elaborated through clinical experience as well as through provings. A proving entails rigorous and detailed observation of the effects of a substance when administered at a sufficient dosage in its crude form and/or as a dynamic or potentized medicine (having been subjected to serial dilution and succussion or vigorous shaking), such that it produces modifications to the state of a person’s health and disposition. The fundamental principle of homeopathic prescribing is that like treats like. In other words, if a substance can cause a certain symptom on the physical, mental/emotional, or dispositional level in a relatively healthy person, then it can in like manner work to treat those same symptoms when they are expressed by a patient who comes seeking care.

Dutch Homeopath Jan Scholten describes the essence of the patient needing potentized coffee (Coffea Arabica) in the following way:

“Coffea is the ideal intellectual worker. They feel stable, focused and self-confident in their mind… They are independent and responsible, following their own plans.”13

The coffea patient often possess a great deal of stability, they are responsible, hard working, persevering, and their actions are well organized and carefully planned. Coffee in its crude form can serve to promote these qualities in people, so it is no wonder that many rely upon it in a culture which emphasizes work, productivity, and efficiency. Scholten explains that the mind of the coffea patient can be active and full of ideas. They can have clear, active, and lucid thoughts, are fast and easy learners with great comprehension skills. They can experience a rush of thoughts, a heightened sense of judgment and sharp and acute states attention. They tend to be quite ambitious people, with a strong and even overpowering need to achieve. They can feel that they must work as hard as possible to fulfill their own expectations, as well as the expectations of their parents (especially the father). Given the great demands that they place upon themselves, and the seriousness with which they approach their assigned tasks and responsibilities, the coffea patient can experience states of pronounced nervous agitation, excitement, exaltation, hilarity, restlessness and irritability – think of the states associated with and over-excitation of the nervous system.

Oversensitiveness is a keynote of this remedy, and all of the senses – sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch – can be greatly heightened. Eating and drinking are things that they do quickly and in a hurried way, as befits their general tendency towards restlessness, hurry, and hyperactivity. The coffea patient may also be the type of person who feels that they cannot live up to the pronounced and unrelenting demands and expectations that they are faced with, and hence suffer from a lack of self confidence, which is improved through the use of stimulants. They feel things intensely, and can have a tendency to exaggerate their emotions and be highly susceptible to the impressions to which they are exposed. Emotional excesses, from extraordinary states of pleasure, optimism, and joy (coffea is a remedy for ailments from excessive joy) to the polar opposite of pronounced despair and despondency, with sharp anger and rudeness. When in this latter state, they can throw everything away, disposing of all that they have been given – in contrast, they can also be excessively clingy, and want to desperately hold on to people and their possessions. They feel pain intensely, and their anguish can run deep. Coffea can have the following delusions: “paradise, magnificent grandeur, beautiful world, heavenly scenes.” They experience states of benevolence and idealism, with a desire to perform good deeds, and veneration for the Supreme Being. Coffea may be prescribed for “ailments from vexation, mortification, frustration; discords between relatives, friends; hurry; anticipation; sudden emotions, pleasurable surprises.” The treatment of a variety of headaches, neuralgic pains and spasmodic afflictions, heart palpitations, digestive disturbances, and states of insomnia may also be addressed with coffea.

In Conclusion…

From our explorations into all things coffee, we may conclude that it is, perhaps more than any other substance in existence, paradigmatic of the culture of modernity. From controversies regarding altered states of consciousness to the regimentation of life brought about through the reign of clock time, from the exploitation of agricultural workers in the 3rd world to meet the needs of the Western consumer to controversies in the medical profession concerning the difference between medicinal and poisonous substances, coffee is both practically and symbolically encoded with many of the most pressing concerns of the culture of modernity. Our investigations into coffee have served to reveal the myriad ways in which everyday substances are always already embedded within and serve to reflect the complex cultural, economic, and political realities in which we exist. The tremendous extent to which plants play a role in shaping human culture through modification of the patterns of human thought and behaviour has also become clear. We have long ago reached the point that our world would be unrecognizable without coffee.

Footnotes:

1 Cemal Kafadar. ‘How Dark is the History of the Night, How Black the Story of Coffee, How Bitter the Tale of Love: The Changing Measure of Leisure and Pleasure in Early Modern Istanbul’ in Medieval and Early Modern Performance in the Eastern Mediterranean, ed. by Arzu Öztürkmenand Evelyn Birge Vitz, lmems 20 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2014).

2Mark Hay. ‘In Istanbul, Drinking Coffee in Public Was Once Punishable by Death.’Atlas Obscura, May 22, 2018. https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/was-coffee-ever-illegal

3 Samuel Hahnemann, The Lesser Writings Of Samuel Hahnemann, ed. and trans. R.E. Dudgeon. New York: William Radde, 1852. Pg. 392.

4 Maria Letícia Galluzzi Bizzo et al. ‘Highlights in the History of Coffee Science Related to Health.’ Science Direct, 7 November 2014. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780124095175000024

5 Joseph Kim et al. ‘Safest Roasting Times of Coffee To Reduce Carcinogenicity.’ PubMed, 1 June 2022. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35226750/#:~:text=Abstract,or%20pesticides%2C%20by%20burning%20off.

6 Alice Nguyen. ‘Bitter Origins: Labor Exploitation in Coffee Production.’ Borgen Project, 24 September, 2020. https://borgenproject.org/labor-exploitation-in-coffee-production/

7 Brian Stoffel. ‘Urban Elites, Organic Farming & The Hypocrisy of No Skin-In-The-Game’. 14 June, 2017.

https://medium.com/@stoffel.brian/urban-elites-organic-farming-the-hypocrisy-of-no-skin-in-the-game-b9f95b655686

8 Mark Fisher. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Oregon: Zero Books,2009. Pg. 18-19.

9 David Hoffmann. Medical Herbalism. Vermont: Healing Art Press, 2003. Pg. 519.

10 Ibid, pg. 124.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid, pg. 365.

13 Jan Scholten. ‘Coffea Arabica.’ QJURE (undated publication). https://qjure.com/remedy/coffea-arabica-2/

Illustrations/Images:

- Illustration: Novel “Coffee: From Plantation to Cup. A Brief History of Coffee Production and Consumption” 1881 [x]

- Photos provided by Serena Mor

Arnica: Materia Medica

Arnica and its Application

Arnica is an herb with a “strange history”, as herbalist Rudolf Weiss comments,

“It used to be very popular, being used internally as well as externally. It is said that the German writer, poet and scientist Goethe would ask for Arnica tea when in his old age he experienced anginal pain due to coronary arteriosclerosis” (Weiss: 1994, 169).

In fact, Goethe claimed that Arnica had saved his life. He sang the praises of Arnica, holding it up as an archetypal healing herb with associations to Helios (the all-knowing God of the sun, of prophecy, and of healing) and Asclepias (son of Helios, the caduceus wielding God of medicine, healing, and rejuvenation who oversees physicians and the practice of the healing arts amongst human beings). Goethe writes:

“Thus I assign Arnica to Helios among the gods. And among men? To the follower of Asclepias who wanders among the lonely heights. Here we have a plant of rapid healing, of firm decision. If you suffer violence and injury, from fist, cudgel or blade, wondrous healing is nigh in this herb. The vital energies are flowing, the pulse grows stronger, the heart takes courage; if the blood has lost its way in a bruise or an effusion, arnica will remind it of its proper courses. Muscles and sinews grow firm; the body form, having suffered insult and injury, is restored, and so is the nervous system where it is so difficult to achieve healing. The organic revolt at injury sustained — we call it pain — lessens and passes.”1

Topical Verses Internal Use

Despite Goethe’s praises, most contemporary authors and practitioners of herbal medicine warn of the dangers of the internal use of Arnica, though it is still widely used topically. The chief indications for the topical use of Arnica include bruises which have resulted from a fall, a blow, or other accidents, as well as poorly healing wounds and leg ulcers.

Weiss notes a traditional use of Arnica tea or tincture (5-10 drops per cup of water) as a gargle to treat sore throat and pharyngitis. “This was found to be most effective with chronic conditions where the circulation was poor in the pharyngeal region, particularly chronic granular pharyngitis, and for chronic smoker’s cough, giving symptomatic relief” (Weiss: 1994, 170).

Arnica provides some of its greatest curative effects in patients who suffer from poor circulation, given its special affinity for the vascular system. In this respect, Arnica covers some of the same clinical indications as does Hawthorn, specifically “senile hearts and coronary artery disease with or without angina” (ibid). Both Arnica and Hawthorn serve to improve the blood supply through the vessels of the coronary artery, though Arnica exerts a pronounced stimulating action in this region and as such is indicated in acute conditions, such as acute weakness of the heart, whereas Hawthorn is better suited for long-term use in chronic cardiovascular conditions such as coronary artery disease, atherosclerosis, and congestive heart failure.

In this author’s opinion, Arnica can and should be used internally by clinical herbalists who have been carefully instructed with respect to its specific indications and proper posology. The risks of the internal use of Arnica include gastric irritation, intoxication with dizziness, tremor, tachycardia, arrhythmia, and collapse (ibid). This is to emphasize the importance of working with a well-trained herbalist, especially when it comes to herbs that carry the potential for adverse events.

Arnica in Homeopathy

To further understand the healing actions of Arnica, let us turn now to homeopathy. Arnica is a very well-known and widely utilized remedy in homeopathic medicine. As in herbal medicine, Arnica is recognized in homeopathy as a remedy that has strong associations with physical trauma and is widely used in the treatment of acute injuries as well as chronic conditions that have resulted as a consequence of a blow, a fall, or some other significant affliction. Examples of such chronic conditions resulting from a significant injury can include: post-traumatic arthritis, neurological damage (e.g. post concussive syndrome), or even a variety of psycho-emotional and cognitive disturbances, such as depression, irritability, uneasiness, and nervous sensitivity. Arnica treats the effects of shock and trauma that have become impressed on the central nervous system.

Arnica, as noted in the above herbal indications, has a strong association with bruising, and is often called upon to help with the reabsorption of blood after surgery. It is always important to treat bruises: bruises create a condition that we can describe as ‘bad blood’, ‘stagnant blood’, or ‘congealed blood.’ This can, in turn, lead to cancerous conditions in the distant future. Put otherwise, where there are bruises on the body, the oxygen supply in the bloodstream to the affected area is compromised. Limited oxygen supply promotes the development and growth of tumours.

Homeopathic medicines are prescribed on the basis of the totality of a patient’s symptomatology, including the mental-emotional and even spiritual levels. The mental-emotional picture of the Arnica patient is someone who feels “bruised by life.” There can be a long history of emotional trauma and a life path that is characterized by difficult knocks and hard falls. This in turn results in a melancholic, morose, and withdrawn disposition. The Arnica patient can come off as standoffish and distant, as someone who dwells on their suffering and wants to be left alone with their pain. They may also be very obstinate and headstrong, unwilling to listen to the opinions and feelings of others. Arnica patients can feel at odds with the world, convinced that it is their fate to always be facing seemingly insurmountable obstacles. Such a patient may have a fear of being touched, and a fear of others approaching, lest she be touched. There may be a fear of death, especially as a consequence of heart disease or a sudden heart attack (this fear may be especially amped up during the night). There can be frightful dreams of being buried alive, of black cats, and of death, nightmares that can startlingly wake the patient from sleep, and which may have commenced after an accident or injury. The Arnica patient can be easily startled as a consequence of prior shocks that have become deeply set in the nervous system. This history of being beaten down and emotionally battered can give rise to chronic rheumatic and arthritic complaints, as well as a variety of skin eruptions and other painful conditions of the skin.

Footnotes:

1 Johann Peter Eckermann, a close associate of Goethe’s towards the end of his life, recorded a detailed account of Goethe’s profound healing experience with arnica in his book ‘Conversations Of Goethe’ (Eckerman: 1998).

References and Recommended Titles:

-

Eckermann, Johann Peter. Conversations of Goethe. Massachusetts: Da Capo Press, 1998.

-

Morrison, Roger. Desktop Guide to Keynotes and Confirmatory Symptoms. Grass Valley: Hahnemann Clinic Publishing, 1993.

-

Sharma, Yubraj. Spiritual Bioenergetics of Homeopathic Materia Medica. London: Academy of Light Ltd., 2019.

-

Weiss, Rudolf. Herbal Medicine. Gothenberg: Ab Arcanum, 1994.

Photos Provided by Serena Mor

Medicinal Mushrooms

An Ancient Medicine

The use of mushrooms as food and medicine stretches back thousands of years, and can be observed in every culture of the world. Recently, a growing body of scientific and clinical evidence has amassed which supports many facets of the traditional use of mushrooms as medicine. Mycotherapy – the science of healing with mushrooms – is fully incorporated into traditional Western herbalism, as well as Traditional Chinese and Japanese medical systems, where mushrooms have always been highly revered as powerful healing agents for a wide variety of ailments and illnesses ranging from acute to chronic. Dr. Walter Ardigò, physician and researcher specializing in mycotherapy, suggests that mushrooms have such a strong affinity for so many diverse disease conditions in the human organism because of their biological similarities to human beings:

“Medicinal mushrooms are more similar to human beings than to plants. Like human beings, they need oxygen to live, eliminate carbondioxide and have no absolute need for light. The two also have similar biological mechanisms, such as immunity, cleansing and elimination of excess fluids” (Ardigò: 2017, 20).

Fungi play innumerable essential roles in maintaining the health and functionality of the world’s diverse ecosystems. It may surprise you, but the largest living being on earth has been declared to be a 2,384 acre large mycelial network (of the species Armillaria ostoyae, also known as honey mushrooms) located in the Blue Mountains of the state of Oregon. Fungi are responsible for processes involving the transmission of information amongst living organisms; they do this by way of electrical impulses that are sent underground through long, thread-like structures called hyphae, which expand to form mycelial networks. Many plants rely on mycorrhizal networks, which facilitate symbiotic associations between plants and fungi. Mycorrhizal networks serve to connect plants together and transfer essentials such as water, carbon, nitrogen, and a host of other nutrients and minerals.

Fungi also play an absolutely pivotal role when it comes to natural processes involving breakdown, decay and regeneration (e.g. by way of returning nutrients to the air and soil). Fungi do no simply decompose, but more accurately work to recompose elements of the environment. Fungi thereby make possible many of the processes of natural evolution. Fungi can be said to occupy a middle ground between the living and the dead; they are what allow for the continuum of coming into being and passing away to exist in the first place. As mycologist Peter McCoy expresses:

“Along the border of living and dying, mycelia sense and digest, interpret and destroy. More visibly than the bacteria with which they work, the fungi walk between worlds, acting as custodians of the darkness. Some species are so intimately tied to decay that they primarily live and fruit from dead animal parts” (McCoy: 2016, 76).

The Power of Mushrooms

That fungi are “custodians of the darkness” is suggestive of the fact that, when used as medicine, mushrooms can be helpful in a wide variety of psycho-emotional disorders, including many varieties of anxiety and depression, trauma and grief. As we will see, mushrooms such as Reishi can help to bring our unconscious defense patterns to light, making the darkness conscious through the metabolization of emotional experience. Additionally, when we understand the role that fungi play in decomposition and regeneration, we can also begin to understand how and why medicinal mushrooms prove so useful in diseases such as cancer and opportunistic infections such as might be associated with HIV. Both of these conditions involve uncontrolled, proliferative growth that the body is unable to keep in check. Medicinal mushrooms act in such a way as to regulate the functioning of the immune system, keeping such pathological conditions in check or preventing their onset in the first place.

Many of our medicinal mushrooms act as adaptogens. In general, adaptogens serve to strengthen the natural defenses of the body, and help the body adapt to non-specific stressors (including physical performance and endurance, as well as psychological and emotional stress). Adaptogens have a normalizing or balancing effect on the whole organism, helping to promote equilibrium amongst different body systems and processes. Many adaptogens have a direct strengthening and rehabilitative effect on the adrenal glands, are known to help to regulate blood sugar levels, and to balance and stabilize hormone levels. Used in moderation, adaptogens are generally very well tolerated by most people and help to promote an overall harmonizing and tonifying effect on the body and mind.

Shiitake

Lentinula edodes

Shiitake is a well-known culinary and medicinal mushroom that has been used in Asian cuisine for at least 2000 years, with cultivation techniques originating in Japan about 700 years ago. The name “shiitake” is derived from the Japanese words “shii” meaning oak, and “take” meaning mushroom: suggesting that shiitake is the mushroom that grows on oak trees. Shiitake is the second most consumed mushroom worldwide, second only to agaricus mushrooms. In Japanese culture, shiitake is considered to be a tonic food substance which serves to increase energy, foster the resilience of the body, reduce the susceptibility to chronic degenerative diseases, aid in convalescence, and slow the aging and deterioration process.

Many clinical studies on Shiitake focus on its production of the beta-glucan lentinan. Beta-glucans are a type of fiber that has an affinity for promoting the health of the heart, regulating the function of the immune system, and balancing cholesterol and blood sugar levels (shiitake is known to be an excellent food for diabetic patients). Lentinan is a unique beta-glucan that is found in shiitake mushrooms, which has been given increasing attention in recent years due to its utility in assisting in the treatment of cancer and HIV infection. Many of the medicinal properties of lentinan relate to its ability to stimulate macrophages (a type of white blood cell in the immune system that engulfs and digests pathogens including cancer cells, foreign substances and harmful microbes), T-cells (which target specific foreign particles in the body), B-cells (an important component of the adaptive immune system), and NK cells (essential to the functioning of the innate immune system). Researchers have also focused on shiitake’s production of the polysaccharides LEM and LAP, which possess significant antitumor activity. LEM has been shown to stimulate the proliferation of a specific type of T-cell which can help to neutralize hepatitis and slow and prevent the rapid development of HIV infection. Shiitake possesses anti-viral and antioxidant properties, in part due to the presence of the essential trace mineral selenium. Selenium plays a role in many bodily functions, especially maintaining thyroid hormone metabolism and DNA synthesis, safeguarding the body against oxidative damage and infection. Shiitake is also useful in diseases of the intestine, respiratory tract, liver, bones and teeth. It has been called on for centuries as a household remedy to help treat flu and fever, coughs and colds and allergies.

There is a growing body of research on shiitake mushroom, which was the first mushroom to receive in depth research by modern scientists. As Ardigò explains:

shiitake “became renowned in 1964, after the Japanese health authorities decided to promote a series of epidemiological studies on the prevalence and distribution of the main chronic diseases throughout the country. The results revealed a very peculiar situation: in two areas of the country, disease was almost entirely absent, and the population was very long-lived” (Ardigò: 2017, 287)

The homeopath Massimo Mangialavori relates that:

“there are many myths and customs associated with shiitake. One belief is that this mushroom grows best in the company of other nurse logs, rather than by itself. Some say the mushroom is sensitive to the attitude of those who tend the mushroom: positive people allow it to flourish; disagreeable people discourage its growth” (Mangialavori: 2017, 263).

Maitake

Grifola frondosa

The general uses of maitake mushroom include the treatment of obesity (the alpha-glucosidase inhibitor contained in maitake decreases the amount of starch that is digested into sugar), diabetes type 1 and 2 (maitake lowers blood glucose levels and enhances insulin sensitivity), a wide variety of tumors but especially those of the stomach and lungs (maitake enhances macrophage activity in the body), leukemia, allergies, and HIV. Maitake has an affinity for conditions of the heart, including hypertension and high VLDL and HDL cholesterol levels. It is also known as a hepatoprotective mushroom, serving to enhance the overall health and functionality of the liver while simultaneously protecting it from damage. It is widely used in hepatocellular cancer and other pathological and chronic conditions that affect the liver, such as hepatitis.

Herbalist Richard Bray comments on the geography and preferred growing conditions of maitake and on the origin of one of its common names, hen of the woods:

“Maitake grows primarily at the base of oak trees in eastern North America, China, and Japan. This polypore mushroom starts as a small fruiting body, about the size of a potato, and when mature reaches up to 2-7 cm across. They grow especially big in Japan, often reaching 45kg. It is known as the “king of mushrooms” there with good reason! Maitake mushrooms grow multitudes of overlapping grayish-brown fronds, which give it the appearance of a hen sitting in the woods, hence the common name” (Bray: 2020, 48).

Lion’s Mane

Hericium erinaceus

Lion’s mane is most well known for its ability to induce brain tissue regeneration and to enhance perceptual capacities. If you look at either fresh or dried lion’s mane, you’ll observe that it appears structurally similar to the human brain and its nerve fibers – a clear example of the doctrine of signatures. Lion’s mane is used in the treatment of such issues as dementia, Parkinson’s, and diabetic neuropathy. The polysaccharides and polypeptides in Lion’s mane help to enhance immune function and have proven useful in stomach, esophageal, and skin cancers. Lion’s mane can pass through the blood-brain barrier and as such is quite valuable for targeting lyme disease spirochetes that have invaded the brain. Lion’s mane directs the spirochetes into the bloodstream where there’s a chance of them being eradicated. There are a growing number of studies that suggest the utility of lion’s mane in treating a variety of types of depression and mood disorders, including hormonally related anxiety disorders.

Indications from Traditional Chinese Medicine include memory disorders, difficulty concentrating, and a general picture of deficient cognitive function and abilities. Traditional Chinese Medicine also recognizes the use of lion’s mane in promoting and maintaining the health of the kidneys, heart, liver, lungs and spleen. It is thought to enhance overall strength and vitality, and facilitate ease of digestion. Ardigò comments:

“in traditional Chinese medicine it has long been used to treat diseases of the stomach, nervous system and nerves, to improve the immune system and to restore the natural strength of the body, because it has an important action in improving energy and cognitive functions. To highlight its many benefits for physical and cognitive activities, the ancient sages have even coined the saying “Hericium nerves of steel and the memory of a lion”” (Ardigò: 2017, 280).

Reishi

Ganoderma spp.

Lingzhi, the name given to ganoderma species in Traditional Chinese Medicine, literally translates as “Supernatural Fungus.” Reishi is also known as “The Mushroom of Immortality.” The physician and scholar Li Shi Zhen (1518 – 1599) wrote that reishi is:

“biter in taste, warm in nature, not poisonous, and replenishes the life energy, or qi of the heart. It increases intellectual capacity while nurturing the body, and banishes forgetfulness; taken over a long period of time, agility of the body will not cease; it keeps the body light and youthful like a celestial being” (quoted in Mangialavori: 2017, 284).

Reishi acts as a cardiovascular, lung, immune and nervous system tonic and restorative, improves circulation and oxygen utilization, promotes deep sleep and undisturbed thought patterns, generates a heightened sense of peacefulness, helps to process stagnant emotions held in the body, and deepens one’s trust in one’s own innate capacities and potentials. As Ron Teeguarden expresses it:

Reishi “calms the mind, eases tension, strengthens the nerves, improves memory, sharpens concentration and focus, [and] and builds willpower”, thus earning it the title “the Mushroom of Spiritual Potency” (Teeguarden: 2000, 88).

Reishi is a medicine that typically is best worked with over a longer period of time, having cumulative effects that gradually build the resilience of our nervous system and transforming the ways in which we relate to and perceive life itself. Reishi is highly esteemed as a medicine in virtually all of the cultures that have access to it, as Ardigò writes:

“Ganoderma, in fact, is known more or less everywhere, not only in Asian countries. For example, research shows that the indigenous peoples of Mexico used it in a number of diseases and in particular for heart disease, both for prevention and treatment” (Ardigò: 2017, 258).

In Traditional Chinese Medicine, reishi is considered to be a supreme Shen tonic, which is to say that it has a special affinity for the spirit, mind, and emotional body. Shen is considered to be the spirit that resides in the heart, or the heart-mind connection. Hence reishi’s reputation as an adaptogen involves its ability to teach us how to develop the inner resources with which we can navigate emotional and spiritual conflicts, and to confront and effectively work through a variety of psychological blockages and obstacles. Reishi has a long reputation in Daoist spiritual traditions as a medicine that promotes wisdom, longevity, groundedness and calmness. As a long living mushroom known to grown in old and mature forests, reishi carries with it the ability to connect us to the nature’s cycles of life, death and rebirth.

Reishi is not only useful for the emotional and spiritual levels of the mind, but also for sharpening cognitive and intellectual abilities and improving concentration and focus. Ardigò comments:

“Ganoderma has also been used at a mental and psychological level, to reduce lapses in concentration, to sharpen intelligence, to improve memory, to strengthen will-power, to relax a distressed and restless mind” (Ardigò: 2017, 258)

Other uses of reishi include: coronary heart disease, heart arrhythmias, feelings of tightness and constriction in the chest, chronic asthma and bronchitis, altitude sickness, vertigo, hypertension, high cholesterol, insomnia, diabetes, hepatitis, cancer, allergies, chronic fatigue syndrome and a variety of conditions involving chronic pain (Mangialavori: 2017, 284 – 285).

Looking into the Future

The future is bright when it comes to medicinal mushrooms. Every year, a greater number of people are becoming involved with the powerful medicine from the kingdom of fungi. From mushroom cultivation to mycoremediation (the use of fungi to help repair and restore damaged and polluted ecosystems), from the treatment of cancer and diabetes to complex emotional and psychological conditions, mushroom medicine can no longer be ignored. More than a passing trend, mushroom medicine is being shown, both by practitioners of natural healing and research scientists from around the world, to offer sustainable and lasting solutions to a wide variety of personal and social health problems. A great deal more will be revealed to us in the years to come as clinical and scientific exploration moves forward and continues to expand in novel and exciting directions.

References and Recommended Titles:

- Ardigò, Walter. Healing With Medicinal Mushrooms: A Practical Handbook. Self published: 2017.

- Bray, Richard. Medicinal Mushrooms: A Practical Guide to Healing Mushrooms. Hamburg: Monkey Publishing, 2020.

- Mangialavori, Massimo. Materia Medica Clinica vol. 2: Fungi. South Carolina: CreateSpace, 2017.

- McCoy, Peter. Radical Mycology: A Treatise On Seeing And Working With Fungi. Portland: Chthaeus Press, 2016.

- Rogers, Robert. The Fungal Pharmacy: The Complete Guide to Medicinal Mushrooms and Lichens of North America. Berkley: North Atlantic Books, 2011.

- Sheldrake, Merlin. Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds & Shape Our Futures. New York: Random House, 2021.

- Stamets, Paul. Mycelium Running: How Mushrooms Can Help Save the World. Berkeley: Ten Speed Press, 2005.

- Teeguarden, Ron. The Ancient Wisdom of the Chinese Tonic Herbs. New York: Grand Central Publishing, 2000.

Photos Provided by Serena Mor

Magic, Healing & Ritual: Herbal Tradition in the Italian Renaissance

Angels, Demons, Herbs and Magic

The ancient, and now largely lost and forgotten, tradition of illuminated herbal manuscripts can tell us much about the practice of herbal medicine throughout antiquity. It was not uncommon for such manuscripts to contain drawings of angels and demons, mythological figures and beings of the celestial hierarchies. Witchcraft and magic were taken to be very serious matters, not only when it came to cultural and religious belief systems, but also when considering the proper training of a physician. As one author writing on traditional Italian healing systems in antiquity has commented:

“Physicians were educated with the notion that drugs had occult powers to affect the body in special ways. It was common belief that demons invaded the soul, and that certain herbs had the property of chasing away devils and demons” (Silberman: 1996).

Expert Italian Renaissance physicians were required to be competent in astronomy and astrology “since the position of the celestial bodies contributed to the occult qualities of a medicinal herb” (Silberman: 1996). The Renaissance, as reflected in the writings of prominent philosophers of the time such as Giordano Bruno and Marsilio Ficino, saw a resurgence of pagan sensibilities. Renaissance thought and imagination embraced an animistic worldview that threatened the established, conservative branches of Christianity and their associated medieval superstitions. As the archetypal psychologist James Hillman writes:

“Renaissance animism led to pluralism, which threatened Christian universal harmony. For when inner soul and outer world reflect each other as enlivened souls and substances, and when the images of these souls and substances are pagan, then the familiar figures of Christianity diminish to only one relative set among many alternatives.”

This co-reflection or mirroring of the inner soul and the outer world are the life-stream of the ancient pagan and Renaissance herbal medical traditions of Italy and surrounding regions. This conception of a pluralistic world and of the enlivened human soul seen as a microcosmic reflection of the greater soul of nature helps us to understand the associations and correspondences that were made between particular herbs, supernatural, celestial, and divine beings, and the actions of the planetary bodies in the medicine of the time.

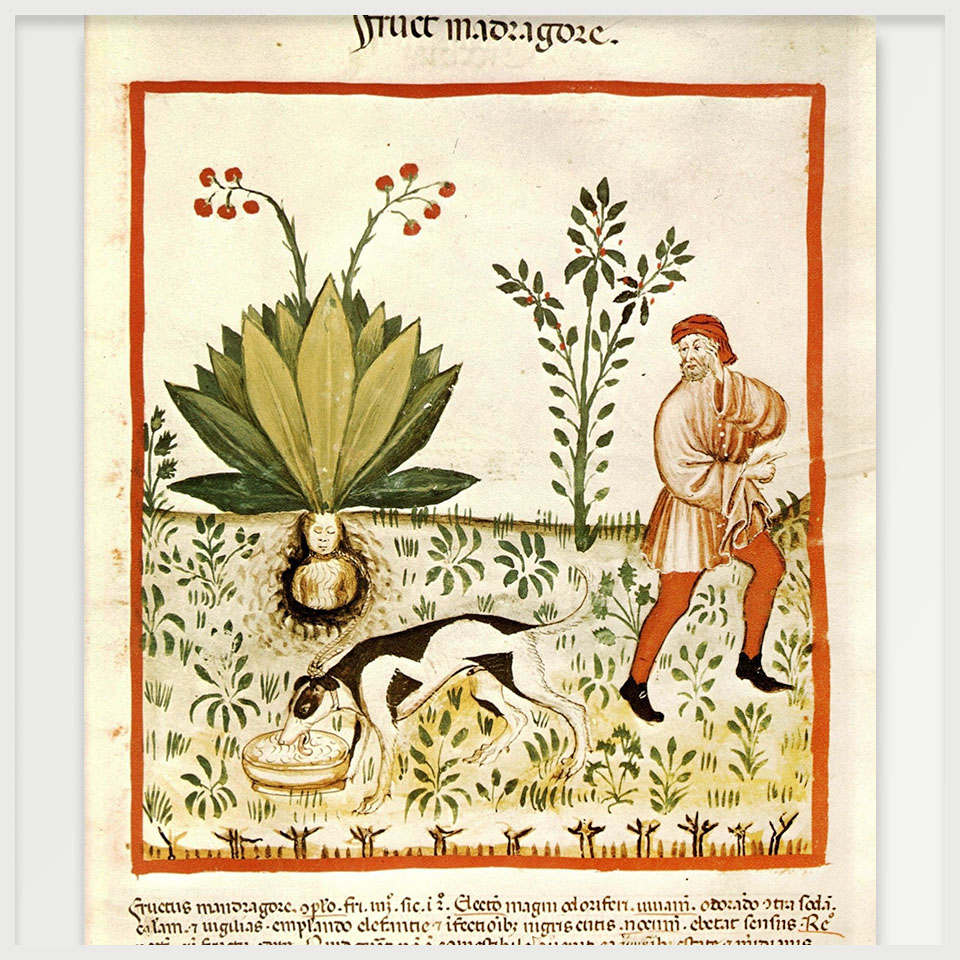

Medicina Antiqua Illustration depicting mandrake harvesting

Christianity and Paganism

In the Middle Ages there was much scorn for the Pagan worship of Goddess nature (who is synonymous with Venus or Aphrodite). This too is reflected in the medical manuscripts of the day. Consider, for example, the “editing” or erasure of an invocation to Gaia found in an early 13th century Viennese manuscript, Medicina Antiqua, by an unknown monk living sometime later in the Medieval period. The erasure in question was found on the back of an image depicting the invocation of the divine mother.

“She stands in classical clothing on the banks of a river in which the river god Neptune can be seen sitting with his trident on a snake. Mother Earth holds a cornucopia in her arms and is surrounded by stylized palms and fantasy plants.” (Müller-Ebeling: 2003, 184).

The fifty-one line invocation on the back of the image originally began “Sacred Goddess Earth, bringer of natural things…” but was changed to “To the Sacred God…” by the monk in question. In the 15th century, much of Northern Europe “fought hard for a reformation of the religious and moral foundations of spiritual life” but in sunny Renaissance Italy there was to be found an opening and renewal of the senses, a “rediscovery of classical sculptures of the gods as well as to texts that were bought from the cloisters by…Cosimo de’Medici” (Müller-Ebeling: 2003, 180).

Italian philosophers and artists of the time were concerned with understanding and exploring nature’s beauty and “the congenial side of the human character [was given much greater attention than was] the sinful” (ibid). A comparison of Germanic and Italian art of this period can be quite revealing; the former tradition is full of images of infernal hells (e.g. Hieronymus Bosch), the latter dedicated to an exploration of anatomy and perspective rooted in a renewed pagan grace (e.g. Leonardo, Raphael, Michelangelo). For confirmation of this claim, one can for example study the encoded pagan symbolism present in Michelangelo’s anatomical drawings.

Pictured: 17th Century Bible

Given the church’s disdain for nature worship and resurgent pagan sensibilities, it is no wonder that Giordano Bruno, the Renaissance magi who considered medicine to be a branch of natural magic, was eventually burned at the stake for heresy (in particular, he was put to death for his belief in an infinite number of worlds). In his treatise De Magia Bruno provides a list of ten definitions of the words magic and magician. The one that especially interests us reads as follows: “Magician: someone who does wondrous things merely by manipulating active and passive powers, as occurs in chemistry, medicine and such fields; this is commonly called ‘natural magic’” (Bruno: 1998). For Bruno, the natural world and the divine world reflected and interpenetrated each other. To use and to understand herbs was to know, in the sense of gnosis, the action of divinity in nature; it was also to realize that through the work of learning to read the book of nature that one in turn serves to illuminate the divine:

“… for as the divinity descends in a certain manner inasmuch as it communicates itself to nature, so there is an ascent made to the divinity by nature, and so through the light which shines in natural things one mounts upward to the life which presides over them” (Bruno quoted in Yates: 1940, 183).

Bruno also gives us an insight into the common practice of using incantations and physical traces left behind by or belonging to a person to affect a cure or to set a curse in motion:

“Wicked or poisonous magic: incantations are associated with a person’s physical parts in any sense; garments, excrement, remnants, footprints and anything which is believed to have made some contact with the person. In that case, and if they are used to untie, fasten, or weaken, then this constitutes the type of magic called ‘wicked’, if it leads to evil. If it leads to good, it is to be counted among the medicines belonging to a certain method and type of medical practice. If it leads to final destruction and death, then it is called ‘poisonous magic’ (Bruno: 1998).”

Hellebore and Mandrake

Not all figures of the Italian renaissance shared the magical and animistic views of Bruno, and the more “rational” voices of the time thought that Bruno and his ilk were quite mad. But even among the more conservative authors, herbal medicine was still widely referenced and bound up with mythological associations. The famous poet Torquato Tasso took issue with Bruno’s worldview and in discussing his work quoted Erasmus’ phrase “Anticyram navigat”, literally ‘set sail for Anticyra’. Anticyra was a place that was known to contain an abundance of the herb hellebore (Veratrum album), then used as a cure for madness (Yates: 1940, 191)). Let us turn to consider this herb, and the related mandrake (Mandragora officinarum), both of which can serve to give us some insights into the practices and belief systems that existed in the Italian herbal tradition, especially the tradition maintained by the rhizotomes, or root diggers, the magician-herbalists of the ancient world.

Hellebore (Veratrum album, white hellebore, veratro bianco in Italian); Helleborus niger, black hellebore) was a very important herb not only in ancient and renaissance Italy but also in Greece, France, and Egypt, among other places. Theophrastus maintained that the two types of hellebore were the most important medicinal plants that were used in ancient Greece and Rome. Contemporary ethnobotanist Christian Rätsch says of the hellebores: “they were the central medicines of the rhizotomes, diggers who nourished the magical plants with shamanic rituals. Hellebore was a sacred plant of the gods” (Rätsch: 2005, 525). Rätsch speculates that name helleboros is derived from hella-bora, which means “food of Helle.” The Hellespont is named after Helle who fell into this body of water after narrowly escaping death. Helle’s stepmother Ino resentfully roasted all of the seeds in the region of Boeotia so that a massive famine would result; this famine she blamed on Helle and her brother Phrixus, the stepchildren she so hated, in a ploy to have them killed. However, a flying golden ram sent by their birth mother Nephele saved these two. Helle fell from the ram into the Hellespont, where she was saved by Poseidon and metamorphosed into a goddess of the sea (in some less interesting accounts of the myth Helle simply drowned).

Rätsch argues that the most important documented use of this herb involved turning the root into a snuff. This is because “the artificially induced sneezing (the German name nieswurz means “sneezing root”) was believed to cause the demons of sickness to leave the body” (ibid). The Greeks and the Romans used the white hellebore1, which was ritually harvested in a way similar to the mandrake (Mandragora officinarum). Pliny gives a detailed account of the uses of white hellebore, which also gives us insight into the nature of medical treatment in the Rome of his time:

The body must be prepared beforehand for seven days by spiced food and abstention from wine, on the fourth and third day through vomiting, on the day preceding through fasting. White hellebore is also given in something sweet but is best in lentils or in a mush… The emptying begins after about four hours; the entire treatment is over in seven hours. In this manner, white hellebore heals epilepsy, …dizziness, melancholy, insanity, possession, white elephantiasis, leprosy, tetanus, tremors, foot gout, dropsy, incipient tympanic water, stomach weakness, charley horse, hip pains, four-day fever, if this will not disappear in any other way, persistent coughing, flatulence, and recurrent stomachaches (Pliny quoted in Rätsch: 2005, 527).

Consideration of the harvesting rituals common to hellebore and mandrake can give us interesting insights into the practices and beliefs of the rhizotomes as they engaged their art in Greek and Italian herbal traditions. The harvesting of these two plants involved many preliminaries and precautions. “Naturally a weird story of perils incurred in obtaining a plant strengthened belief in its magic powers and added to its commercial value” (Randolph, 489). Theophrastus describes the practices of the root diggers in his History of Plants, with specific reference to the mandrake: “Around the mandragora one must make three circles with a sword, and dig looking toward the west. Another person must dance about in a circle and pronounce a great many aphrodisiac formulas” (Theophrastus quoted in Randolph: 1905, 489). He also mentions the necessity of standing with one’s back to the wind so as not to be exposed to strong odours that some plants may emit, and anointing any skin not covered by clothing as a means of protection and defense. Other practices involved the “digging of certain plants only by night, [and] avoiding the sight of certain birds” (Randolph: 1905, 489). There were variations on these practices that depended on the plant being harvested and the uses for which it was intended. While the mandrake was to be dug up with one’s back facing west, hellebore was to be dug with one’s back facing east. Theophrastus notes that the practice of repeating aphrodisiac formulas as part of the harvesting of mandragora shows great similarities to the practice of repeating curses when sowing cumin seeds (Randolph: 1905, 490).

Mandrake Harvesting Illustrated in the Tacuinum Sanitatis manuscript, 1390

Pliny borrowed a great deal from Theophrastus and the account found in his Natural History of the practices of the root diggers and the harvesting of the mandrake in particular is one indication of this: “Those who are about to dig mandragora avoid a wind blowing in their faces; first they make three circles with a sword, and then dig looking toward the west” (Pliny quoted in Randolph: 1905, 490). We can notice however that Pliny says nothing of the “great many aphrodisiac formulas” that Theophrastus mentions in his account of the practices of the rhizotomes. Randolph suggests that “the omission by Pliny of any reference to aphrodisiac formulas is easily explained by his declaration that he will say nothing in his work about aphrodisiacs or magic spells except what may be necessary to refute belief in their efficacy” (Randolph: 1905, 490). This stance again speaks to the differences that existed in the ancient world between those who subscribed to the views and practices of natural magic and those who saw such a worldview as a breed of madness that must be rejected and defeated.

Aphrodisiacs were highly valued in Mediterranean herbal traditions, and one of the greatest of all of the aphrodisiacs was the mandrake. Rätsch comments that “in ancient times, the primary ritual significance of the mandrake was in erotic cults” (Rätsch: 2005, 348). However, only poor quality source material describing this usage remains and so detailed information about these practices is not available to us. Apart from its uses as an aphrodisiac, the mandrake was also widely used in medicine. Dioscorides:

A juice is prepared from the cortex of the bark by crushing this while fresh and pressing this; it must then be placed in the sun and stored in an earthen vessel after it has thickened. The juice of the apples is prepared in a similar manner, but this yields a less potent juice. The cortex of the root that is pulled off all the way around is put on a string and hung up to store. Some boil the roots with wine until only a third part remains, clarify this and then put it away, so that they may use a cup of this for sleeplessness and immoderate pain, and also to induce lack of sensation in those who need to be cut or burned themselves. The juice, drunk in a weight of two obols with honey mead, brings up the mucus and the black bile like hellebore; the consumption of more will take life away (Dioscorides quoted in Rätsch: 2005, 348).

The root diggers would only dig up the mandrake on the “day of Venus”, Venus of course being the Goddess of Love, which further suggests that one of the greatest virtues attributed to the mandrake in the ancient world was as an aphrodisiac, an agent in love magic/erotic rites (Randolph: 1905, 494). The mandrake is well known for its anthropomorphic appearance, and it is common in herbal traditions from around the world to attribute special healing powers to plants that resemble the human form (one can also think of the enormous sums that are paid in China even today for ginseng roots which look like human beings). Dioscorides and Pliny both make reference to a “male” and a “female” species of the mandrake but as Randolph clarifies “these terms, which the ancients applied to many plants, have nothing to do with sex, but signify more robust species (i.e., those having larger leaves, roots, etc., and attaining a greater height) and their opposites” (ibid).

The Goddess Circe