For the Love of Our Landscapes

Manicured Gardens and Lawns

For so long, most western societies have valued groomed lawns and manicured gardens; those considered beautiful for their lack of weeds, crisp edges and often symmetrical landscaping. Having lived in urban areas most of my life, it wasn’t until moving to the Bruce Peninsula that I felt a sense of belonging, being surrounded by many other wild and weedy places. However, as our climate continues to change, more and more people are in search of ways to change course from the predicted direction we are headed for.

Depending on where you live, some of these impacts may be more noticeable, and in other places, less so. However, on a global scale, many parts of the world are experiencing the effects of rising sea levels, extreme temperatures and warming oceans. Our climate here in Canada is warming twice as fast as the global average. Biodiversity and habitat loss may also be observed, as the conditions of our own health continue to change, while the landscapes around us do too.

Though there are many clever and remarkable ways conservationists are trying to slow the pace of climate change (including the implementation of nature-based solutions and other effective area-based conservation measures), recognizing that many individuals and organizations are implementing strategies to reduce waste and emissions, I would argue that now is time for a change of narrative and for redefining the admirable qualities of the lands that surround us. Whether it be our backyards, community gardens or city parks, these are all opportunities to work together in support of a regenerative way forward, paying respect to every element of life that can help us fight climate change.

Of course, allowing for a wilder landscape is only one of the many actions we can take, it is one that has a cascade of positive outcomes. By creating these naturalized spaces, more land is being added to wildlife corridors (which can exist in different scales and ways), where all forms of life — mammals, birds, fish, amphibians and reptiles — can migrate, feed and drink, and we are connecting more habitats for them to move through as they continue through their different stages of life. Corridors may not have to be continuous, large or perfect to still help.

A part of my lawn where only a walking path is mowed and other tall grasses, asters, black-eyed Susans, and more are allowed to flourish

The Impact on Our Own Land

Living in a household surrounded by a naturalized lawn on the Bruce Peninsula of southwestern Ontario, I’ve witnessed these words that I share come to life. Since mowing only enough space for walking paths, planting a vegetable garden and a firepit, my family and I have been able to give back just under half a hectare of land to nature in hopes of creating a small, but thriving, ecosystem. The birdsong, combining melodies of meadowlarks, buntings, blue and blackbirds, sparrows and robins, cheers us along, as we continue to tend to the abundance of new-to-us species — black-eyed Susan, common yarrow, gray goldenrod, and a colourful variety of asters (to name but a few). Though this requires some work, these efforts promote a yard that is, in many ways, self-sufficient.

Another approach to consider is creating a food forest, or planting a diverse array of edible species, in an attempt to mimic the ecosystems and patterns found in nature. This will typically include canopy layers of fruit and nut trees, berry bushes and shrubs, herbaceous plants valuable for food and medicine, ground covers, and, at the root layer, fungi and harvestable root vegetables (this is also a great opportunity to learn what’s native to your area, and to incorporate habitat for species at risk). This concept considers the many necessary layers for maintaining symbiotic relationships, from the tallest tree to the ground below while also creating food for those doing the planting and the species passing through.

In some cases, municipalities have bylaws about what you can do with your outside areas, ensuring you meet a standard or level of care throughout your subdivision or community. Finding out what policies exist can be a great way to spark change.

Other Ways to Contribute

All this said, more and more people today are taking up residence in urban areas, including suburban neighbourhoods with little to no backyard, condos and apartments, group and community housing. This doesn’t mean you can’t make a difference, though! Along with starting conversations and sparking change, community gardens are another great addition to wildlife corridors, and they usually start thanks to the efforts of one or few people. This can be a great way to build community in an effort toward a viable and more biodiverse future, which will further awareness of the importance of maintaining our greenspaces.

Change doesn’t happen overnight. I encourage you to take a look around you. See the landscapes, both large and small, as opportunities to create food, habitats and pathways for those we share our world with, and remember that we are only as resilient as our ecosystems.

Photos Provided by Chelsea Vieira

Coffee: The Good the Bad and the Ugly

An Historic Global Enterprise

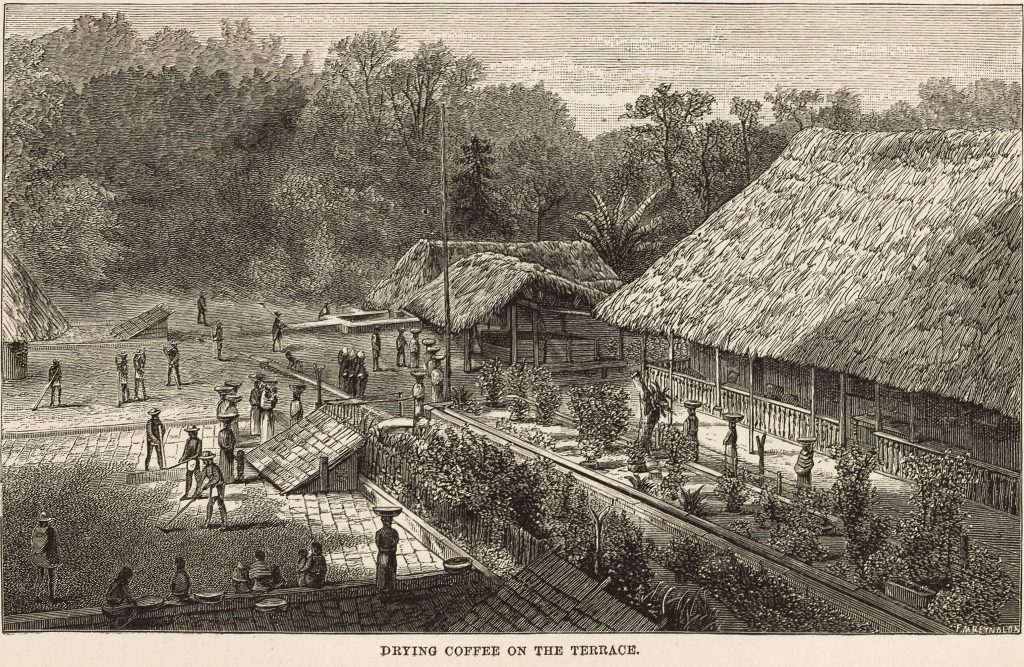

Coffee is one of the most ubiquitous and widely consumed beverages in the world, second only to water. The already extraordinary demand for coffee only seems to be increasing; global coffee production reached 175.35 million 60-kilogram bags as of 2020/2021, increasing from about 165 million 60-kilogram bags in 2019/2020.

Coffee drinking, and the knowledge of the coffee tree as a medicinal substance, dates back to at least the mid 15th century, where we find our first credible historical evidence pertaining to its use in the accounts of Yemini author Ahmed al-Ghaffar. The coffee tree was most likely introduced into Yemen by way of trade routes with Ethiopia from across the Red Sea. Thus, given that the coffee tree was being traded and exported from Africa, it is highly unlikely that its medicinal, recreational, and social values were only realized in the 15th century, in a country where the tree itself was not native. The use of coffee almost certainly reaches back much further than the 15th century, though specifics concerning its initial discovery by the peoples of the African continent and its use in their traditional systems of medicine and culture remain obscure.

When it comes to the earliest detailed historical records concerning the use of coffee, we can look to the work of Harvard historian Cemal Kafadar, where it is revealed that the social significance of coffee in Islamic society was established by way of its use in Sufi religious rituals:

“To turn to the early history of coffee and coffeehouses, more specifically, there must have been many instances when coffee was consumed as a plant found in the natural environment of Ethiopia and Yemen, but the earliest users who regularized its consumption as a social beverage, to the best of our knowledge, were Sufis in Yemen at the turn of the fifteenth century. Evidently, they discovered that coffee gave them a certain nimbleness of the mind, which they were keen on cultivating during their night-time vigils and symposia. Thus started the long history of the appreciation of coffee as a companion to mental exercise and conviviality, particularly when one wished to stretch or manipulate the biological and social clock.”1

The Start of The Coffee House Phenomenon

It is from this point onward that coffee houses started to appear across Arabia and gradually, over the next three centuries, throughout the rest of the world. The historical significance of the coffee house is inextricably bound up with the historical significance of coffee itself; the coffee house has always served as a kind of public institution and cultural hub through which all manner of information – from the common and mundane to the revolutionary and political – was shared and disseminated amongst the population. Even today, in a world increasingly characterized by digital identities and disembodied forms of social engagement, the coffee house still serves as a place of respite, where people can turn for a semblance of embodied interpersonal interaction and exchange in an evermore alienating and depersonalizing world.

Coffee’s appearance in Europe (especially England and Germany) in the late 17th century coincided with the discovery that clocks could be controlled by harmonic oscillators. This was followed in the 18th century by a series of technological discoveries and breakthrough inventions that lead to increasingly precise clocks, and hence to a heretofore unimaginable regimentation of time itself. Is it a mere coincidence that coffee – utilized by so many for the purposes of maintaining attention and increasing stamina – came to Europe just as machine production and the Industrial Revolution, with the inhuman demands it placed on workers, led to a decline in hand production and the artisanal trades of the past? From the perspective of cultural history, coffee has a dual identity; as a tool for social conviviality and the free flow and exchange of ideas (exemplified by the institution of the coffee house), as well as a crucial ingredient in the engineering of the industrial worker, allowing for the kind of over-stimulation that is required to meet the demands of the fast paced, mechanized world of industrial society. The hegemony of standardized clock time, and the counting of seconds, minutes and hours as measures of productivity and profitability, violated the natural diurnal rhythms that human beings had always used to orient their lives. The question remains as to the extent to which coffee played a role in one of the biggest cultural shifts in recorded history.

Historical Religion and Politics

The opinion of the medical profession with respect to coffee has been divided throughout history. Coffee is exemplary when it comes to demonstrating the degree to which medical opinion can be deeply influenced and shaped by cultural and political trends and assumptions. Indeed, the medical, socio-political and religious views of coffee were at times inextricably bound up with each other, making it next to impossible to disentangle one from the other. Where does religious belief end and medical “fact” begin? We can explore this issue by taking a closer at the early history of coffee in the Islamic world, and the changing tide of opinion with respect to the most influential and powerful drink in the world, next to water itself.

In contrast to the view that the introduction of coffee into liturgical practice was a great blessing in that it allowed worshipers to better execute their devotions to God, other religious scholars argued that coffee should be outlawed insofar as it had never been mentioned in the Quran. Many of these scholars were also concerned about what they perceived to be the deleterious health consequences of coffee consumption. But this controversy is even further muddied when we stop to consider the political climate of the time. While some commentators argue that the various attempts to outlaw coffee in the Islamic world were a consequence of religious and medical opinion, the truth is more likely that coffee (and the social revolution spurred by the birth of the coffee house) was perceived as a political threat.

“Between the early 16th and late 18th centuries, a host of religious influencers and secular leaders, many but hardly all in the Ottoman Empire, took a crack at suppressing the black brew. Few of them did so because they thought coffee’s mild mind-altering effects meant it was an objectionable narcotic (a common assumption). Instead most, including Murad IV [the Ottoman sultan who issued a ban on coffee in 1633], seemed to believe that coffee shops could erode social norms, encourage dangerous thoughts or speech, and even directly foment seditious plots.”2

In what is perhaps an unexpected twist, our brief survey of the cultural and political history of coffee has revealed the extent to which many of our deeply held assumptions, sometimes taken as objective fact, in actuality rest upon a socio-political and theological underpinning of opinion and currents of dogmatic belief which colour our perception, of which we may be mostly or even totally oblivious.

PART II: Coffee as Medicine, Coffee as Poison

What is the difference between a food and a medicine? In his essay from 1803 titled ‘On the Effects of Coffee’, Samuel Hahnemann (the founder of homeopathy) set out to clarify this distinction and to warn of the deleterious effects of the unchecked consumption of medicinal substances, taking coffee as a paradigmatic example. Hahnemann writes:

“Medicinal things are substances that do not nourish, but alter the healthy condition of the body; any alteration, however, in the healthy state of the body constitutes a kind of abnormal, morbid condition. Coffee is a purely medicinal substance. All medicines have, in strong doses, a noxious action on the sensations of the healthy individual. No one ever smoked tobacco for the first time in his life without disgust; no healthy person ever drank unsugared black coffee for the first time in his life with gusto — a hint given by nature to shun the first occasion for transgressing the laws of health, and not to trample so frivolously under our feet the warning instinct implanted in us for the preservation of our life.”3

A medicine is a substance that serves to alter the state of health, whereas a food is a substance that serves to provide nourishment. When medicines are taken in excess, or when they are not properly indicated for an individual person, they can produce an abnormal or even pathological condition. Medicines can preserve life and maintain health, though they can also derange the state of health and take life away when they are given without the requisite attention or care. Food substances can likewise produce states of disease if they are eaten to excess, though the deleterious effects of foods generally take a much longer time to manifest when compared to the stronger power of medicinal substances to affect deep seated changes on the level of constitutional vitality.

While in 1803 Hahnemann condemned the use of coffee, going to so far as to argue that its unchecked consumption was the origin of many of the chronic diseases that plagued humanity, he later toned down his opinion, having developed a much more sophisticated theory of the origins of chronic diseases by way of the concept of the miasms (the 18th century precursor to our contemporary theories of epigenetics, and one of the philosophical foundations of homeopathic medical practice to this day). Nevertheless, Hahnemann was right to emphasize the extent to which medicinal substances, when treated as foods and consumed injudiciously, can exert profound effects on the state of health. This is especially true if conditions of heightened susceptibility to a given substance are at play in an individual’s constitution (think here of the example of severe allergic reactions to substances that to most people are extremely benign). Human response to coffee and to caffeine varies widely, and like any assessment of a medicinal substance, individual response patterns must always be given a higher regard than overly generalized, universal theories and pronouncements. The difference between a medicine and a poison is ultimately in the dose, and the effect of the dose is always weighed in relation to the individual to whom it is administered.

The Hahnemann of 1803 represents one extreme when it comes to thinking about coffee as medicine. A look at the medical literature on coffee, from from the 15th century to the present day, is full of contradictory and opposing points of view. Coffee was for centuries listed in the pharmacological and medical literature that herbal and Eclectic physicians relied upon, such as the Codex Medicus. Coffee remained classified as a medicinal substance in materia medica and pharmacopoeias until the twentieth century, when the use of natural medicinal substances was largely supplanted by the products of the petrochemical drug industry. Maria Letícia Galluzzi Bizzo et al. recount some of the claims made about coffee in the medical traditions of the West, emphasizing and siding with the view of coffee as a universal elixir of health (the poplar opposite of Hahnemann’s position):

“As a panacea, coffee has been prescribed as infusions, capsules, potions, or injections against a vast spectrum of diseases— from hernias to rheumatism, from colds to bronchitis. In the first half of the nineteenth century, medical controversies underlined the therapeutic use of caffeine in chronic conditions such as heart and circulation problems because of difficulties establishing the proper doses and the risk of toxicity to the heart. Nevertheless, the notion that such use would be safe prevailed. Recent research has opened new horizons regarding the use of coffee as a medicine, with discoveries of possible distinct preventive and curative applications of coffee’s substances.”4

The Coffee of Today

The medical opinions of the past are in many ways inadequate when it comes to judging the effects of coffee today. The coffee of the 1800s is not the coffee of the 21st century. Consider, for example, the question of pesticides. Only about 3% of the world’s coffee supply today is produced using organic methods, and we now know that the residues of pesticides found on coffee beans, one of the most pesticide ridden agricultural products in the world, are for the most part not destroyed by the roasting process. Many countries that produce coffee use pesticides that have been banned in North America and Europe over health and safety concerns, and a significant number of the countries which import this coffee do not have maximum residue limits (MRLs) when it comes to the pesticides that are used and can be detected on the harvested coffee beans.

Mold is yet another issue. When not stored in a temperature controlled storage facility, coffee beans are also highly susceptible to developing mold, which comes with its own host of long term adverse health effects. Even roasting techniques have a great bearing on coffee’s potential effects on one’s state of health. One study carried out by the International Association for Food Protection, for example, comes to the following ambiguous conclusion concerning the question of the carcinogenicity of coffee and how this is affected by the roasting process:

“Roasting coffee results in not only the creation of carcinogens such as acrylamide, furan, and poly-cyclic aromatic hydrocarbons but also the elimination of carcinogens in raw coffee beans, such as endotoxins, preservatives, or pesticides, by burning off. However, it has not been determined whether the concentrations of these carcinogens are sufficient to make either light or dark roast coffee more carcinogenic in a living organism.”5

There are a whole host of other socio-economic and political considerations that should be borne in mind with respect to the global coffee industry of the 21st century. Health is not a purely individual consideration; the health of your body and mind are indissociably bound up with the functioning of the larger natural and artificial systems in which you exist. We are unwitting participants in a global system of capitalist exploitation which, through the untiring impulses of profitability and expansion, inevitably leads towards the total degeneration of the natural world and the complete immiseration of its inhabitants. A sober and careful look at coffee and its economic, political, and agricultural ramifications, inevitably alerts us to a confrontation with this reality.

Capitalism, Globalization, and the Politics of Coffee Production:

The pesticide residues found in your average bag of coffee are inconsequential in comparison to the toxicity that third world coffee farmers are exposed to on a daily basis. These farmers, in addition to the dire health consequences of chronic chemical exposure that are an unavoidable part of their work, lead lives that are dictated by the brutal conditions of strenuous labour, physical exploitation and the inter-generational cycles of inescapable poverty, child labour and indentured servitude. Alice Nguyen, in an article written for The Borgen Project (a non-profit organization dedicated to addressing the global issues of poverty and hunger), unflinchingly encapsulates these issues:

“Growing coffee requires intensive manual work such as picking, sorting, pruning, weeding, spraying, fertilizing and transporting products. Plantation workers often toil under intense heat for up to 10 hours a day, and many face debt bondage and serious health risks due to exposure to dangerous agrochemicals. In Guatemala, coffee pickers often receive a daily quota of 45 kilograms just to earn the minimum wage: $3 a day. To meet this minimum demand, parents often pull their children out of school to work with them. This pattern of behavior jeopardizes children’s health and education in underdeveloped rural areas, where they already experience significant barriers and setbacks.”6

Facts like these seem to underlie the importance of Fairtrade and Organic Certification for coffee and related products, which in principle strive to ensure sustainable development, equitable trading conditions, and giving autonomy back to marginalized farmers and agricultural workers. However, consumers in the Western world must not fall into the self-congratulatory trap of thinking themselves morally superior because they are able to afford the often vastly more expensive Organic and Fairtrade Certified products that are simply outside of the economic reach of many. The reality is that, in many instances, the increased profits from organically grown coffee products do not reach the farmers and laborers themselves, but end up lining the pockets of the distributors, who in many regions of the world function in similar ways as do drug cartels.

What is more, there are the significant and rarely discussed pitfalls of introducing organic agricultural techniques to farmers who work on lands that have been treated with chemical pesticides for decades. Such agricultural land will require significant time and effort in order to be rehabilitated such that organic farming can be sustained there. This means that farmers who are already struggling to maintain their operations run the risk of falling even further into economic enslavement if they are coerced into adopting the organic methods that righteous and ecologically minded politicians, consumers, academics and other self proclaimed “experts” in the Western world preach about with moral fervour.

Consider the following story, told by the son of a soybean farmer working in El Toledo, Costa Rica. He recalls a childhood memory of the year his father was convinced by Penn State University professors to adopt organic agricultural techniques, under the promise of increased profitability and the ecological restoration of their farmland:

“The professors convinced my dad to make a wholesale change from conventional soybean farming to organic. They warned him that he might lose up to 15% of his yield, but that this would be offset by a number of factors: He could sell his soybeans for more, as they were organic. His soil would be healthier. He would spend less on chemical inputs, and thus save money. The reality was very different. Instead of losing 15% of our yield, we lost 50%. Instead of spending less money, he spent more: the gas he spent to tractor over the weeds alone outstripped his usual chemical spending.

He ended up taking a job in a factory to avoid bankruptcy. All I remember is that when I was eight, I never saw my dad: he was either weeding the soybeans or at the factory. As soon as that season ended, we went back to chemical farming.”7

Many such stories, pertaining to all manner of farming from all parts of the world, can be found if one cares to look beyond the ‘Certified Organic’ and ‘Fairtrade’ labels that one sees plastered on one’s favourite products lining the local supermarket shelves. From coffee and soybeans to chocolate and Brazil nuts and beyond, the exploitation of labourers and the degeneration of the world’s ecosystems are part and parcel of our contemporary agricultural systems of production, whether conventional or organic. Any consideration of “sustainability” must always be understood within the framework of the global capitalist economic system in which we exist. As the political and cultural theorist Mark Fisher so poignantly put it in his book Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?:

“The relationship between capitalism and eco-disaster is neither coincidental nor accidental: capital’s ‘need of a constantly expanding market’, its ‘growth fetish’, mean that capitalism is by its very nature opposed to any notion of sustainability.”8

The preceding section of this article is not intended to inculcate feelings of guilt, a sentiment which only leads to a place of demoralization and further defeat. Rather, it was written out of an honest assessment of the situation in which we all find ourselves as consumers in a system which, in its vast complexity, far transcends the individual decisions that you and I make on a daily basis. It is only from a place of sober awareness that a genuine desire for a better world can be nurtured and allowed to bear fruit.

And now, with these economic, cultural and political factors in mind, let us turn to consider the detailed effects of coffee from a more purely medical perspective. A well rounded discussion of coffee requires that we adopt a multi-perspective view. Single vision is, after all, what the capitalist system of exploitation itself is based on.

PART III: Coffee’s Medicinal Effects: What Can Reliably Be Said?

Coffee is a nervine stimulant, i.e. an herb that causes excitation and stimulation of the nervous system, specifically by engaging or heightening the activity of the sympathetic nervous system. The most widely known and discussed function of the sympathetic nervous system is the mediation of the neuronal and hormonal stress response pattern known as the fight-or-flight response. The sympathetic nervous system is what allows the body to quickly react and respond to situations of threat and danger, to situations that threaten survival. But the sympathetic nervous system cannot be adequately understood if we look at it as an isolated regulatory or physiological function. The sympathetic nervous system works in concert with the parasympathetic nervous system and together make up what is called the autonomic nervous system. The autonomic nervous system regulates and controls many of the functions of the body’s internal organs. When we consider the interdependence and co-functioning of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, then we can begin to understand that the stress response typically associated with the sympathetic nervous system is one pole or extreme of a greater homeostatic controlling mechanism which oversees the feeling and function of the human organism on many levels.

However, excessive stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system can and does result in undue consequences. Herbalist David Hoffmann explains the action of nervine stimulant herbs, and relates their functions to the excessively heightened states of excitation that characterize the frantic and overwrought patterns of 21st century existence:

“Direct stimulation of nervous tissue is not often needed in our hyperactive modern lives. In most cases, it is more appropriate to stimulate the body’s innate vitality with the help of nervine or bitter tonics. These herbs work to augment bodily harmony, and thus have a much deeper and longer-lasting effect than nervine stimulants. In the 19th century, herbalists placed much more emphasis upon stimulant herbs. It is, perhaps, a sign of our times that the world now supplies us with more than enough stimulation. When direct nervine stimulation is indicated, the best herb to use is Cola acuminata, although Paidlinia cupana, Coffea arahica, Ilex paraguayensis, and Camellia sinensis may also be used. One problem with these commonly used stimulants is their side effects; they are themselves implicated in the development of certain minor psychological problems, such as anxiety and tension. Some of the volatile oil-rich herbs are also valuable stimulants. Some of the best and most common are Rosmarinus officinalis and Mentha piperita.”9

Caffeine is the most widely recognized and studied active ingredient in coffee as well as many other stimulant herbs (such as those listed in the above quotation). But coffee also contains a wide array of other important constituents such as tannins, fixed oils, carbohydrates, and proteins, which should not be forgotten, as coffee, just like all herbs, are irreducible to their component parts. It is through the roasting process that caffeine is liberated from the raw coffee bean. Caffeine produces diuretic and stimulant effects, specifically on the respiratory, cardiovascular and central nervous systems.10 Caffeine is also an analgesic adjuvant, and hence is incorporated into a wide number of proprietary aspirin and acetaminophen preparations.11 Coffee also contains phytoestrogens, which have been subject of a great deal of scientific debate. Phytoestrogens can play a role in addressing symptoms and conditions caused by estrogen deficiency, which may be especially pronounced in premenopausal and post-menopausal women. They are also implicated in memory and learning processes and have been shown to possess anxiolytic effects. The research into the effects of phytoestrogens on human health is still ongoing, and is a fruitful and fascinating area of research. For example, consider the fact that the consumption of beer, bourbon, mescaline, cannabis, and coffee all produce phytoestrogenic effects – the relationship between psychoactivity and phytoestrogenic compounds certainly needs to be more deeply explored!

When it comes to consider possible contraindications and adverse reactions from coffee consumption, we should note that coffee, along with fried and fatty foods, chocolate and alcoholic beverages, can lead to or serve to aggravate LES dysfunction (the lower esophageal sphincter, which links the esophagus and the stomach). Obesity, pregnancy, cigarette smoking, and a structural weakness of the diaphragm known as hiatus hernia can also contribute to a weakening of the LES. If the LES fails to properly close, stomach acid can easily splash up from the stomach into the esophagus, leading to severe acid reflux and heartburn. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (commonly known by the acronym GERD) is associated with a leaking of stomach contents back into the esophagus. When there is a prolonged period of LES dysfunction, this can lead to acid and chemical damage of the esophagus, that is, to GERD.

The consumption of coffee and other caffeine containing substances can also result in headaches. The headaches that are associated with coffee consumption are often related to caffeine dependence, which can lead to significant withdrawal symptoms in some individuals. As Hoffmann writes:

“Caffeine can cause headaches by increasing the body’s expectation for it. When blood levels of caffeine drop, symptoms of withdrawal, including headache, may set in. That’s why some heavy coffee drinkers experience “morning headache” until they have that first cup of coffee. Caffeine headaches are usually experienced as a dull, throbbing pain on both sides of the head. Once the body rids itself of caffeine, the headaches disappear on their own. Such headache sufferers, however, are often unaware that their problem is due to caffeine and will continue to drink coffee, ensuring that the problem will recur.”12

We can look to the homeopathic literature to round out our consideration of the spectrum of effects that coffee can have. In homeopathy, the medicinal effects of a given substance are elaborated through clinical experience as well as through provings. A proving entails rigorous and detailed observation of the effects of a substance when administered at a sufficient dosage in its crude form and/or as a dynamic or potentized medicine (having been subjected to serial dilution and succussion or vigorous shaking), such that it produces modifications to the state of a person’s health and disposition. The fundamental principle of homeopathic prescribing is that like treats like. In other words, if a substance can cause a certain symptom on the physical, mental/emotional, or dispositional level in a relatively healthy person, then it can in like manner work to treat those same symptoms when they are expressed by a patient who comes seeking care.

Dutch Homeopath Jan Scholten describes the essence of the patient needing potentized coffee (Coffea Arabica) in the following way:

“Coffea is the ideal intellectual worker. They feel stable, focused and self-confident in their mind… They are independent and responsible, following their own plans.”13

The coffea patient often possess a great deal of stability, they are responsible, hard working, persevering, and their actions are well organized and carefully planned. Coffee in its crude form can serve to promote these qualities in people, so it is no wonder that many rely upon it in a culture which emphasizes work, productivity, and efficiency. Scholten explains that the mind of the coffea patient can be active and full of ideas. They can have clear, active, and lucid thoughts, are fast and easy learners with great comprehension skills. They can experience a rush of thoughts, a heightened sense of judgment and sharp and acute states attention. They tend to be quite ambitious people, with a strong and even overpowering need to achieve. They can feel that they must work as hard as possible to fulfill their own expectations, as well as the expectations of their parents (especially the father). Given the great demands that they place upon themselves, and the seriousness with which they approach their assigned tasks and responsibilities, the coffea patient can experience states of pronounced nervous agitation, excitement, exaltation, hilarity, restlessness and irritability – think of the states associated with and over-excitation of the nervous system.

Oversensitiveness is a keynote of this remedy, and all of the senses – sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch – can be greatly heightened. Eating and drinking are things that they do quickly and in a hurried way, as befits their general tendency towards restlessness, hurry, and hyperactivity. The coffea patient may also be the type of person who feels that they cannot live up to the pronounced and unrelenting demands and expectations that they are faced with, and hence suffer from a lack of self confidence, which is improved through the use of stimulants. They feel things intensely, and can have a tendency to exaggerate their emotions and be highly susceptible to the impressions to which they are exposed. Emotional excesses, from extraordinary states of pleasure, optimism, and joy (coffea is a remedy for ailments from excessive joy) to the polar opposite of pronounced despair and despondency, with sharp anger and rudeness. When in this latter state, they can throw everything away, disposing of all that they have been given – in contrast, they can also be excessively clingy, and want to desperately hold on to people and their possessions. They feel pain intensely, and their anguish can run deep. Coffea can have the following delusions: “paradise, magnificent grandeur, beautiful world, heavenly scenes.” They experience states of benevolence and idealism, with a desire to perform good deeds, and veneration for the Supreme Being. Coffea may be prescribed for “ailments from vexation, mortification, frustration; discords between relatives, friends; hurry; anticipation; sudden emotions, pleasurable surprises.” The treatment of a variety of headaches, neuralgic pains and spasmodic afflictions, heart palpitations, digestive disturbances, and states of insomnia may also be addressed with coffea.

In Conclusion…

From our explorations into all things coffee, we may conclude that it is, perhaps more than any other substance in existence, paradigmatic of the culture of modernity. From controversies regarding altered states of consciousness to the regimentation of life brought about through the reign of clock time, from the exploitation of agricultural workers in the 3rd world to meet the needs of the Western consumer to controversies in the medical profession concerning the difference between medicinal and poisonous substances, coffee is both practically and symbolically encoded with many of the most pressing concerns of the culture of modernity. Our investigations into coffee have served to reveal the myriad ways in which everyday substances are always already embedded within and serve to reflect the complex cultural, economic, and political realities in which we exist. The tremendous extent to which plants play a role in shaping human culture through modification of the patterns of human thought and behaviour has also become clear. We have long ago reached the point that our world would be unrecognizable without coffee.

Footnotes:

1 Cemal Kafadar. ‘How Dark is the History of the Night, How Black the Story of Coffee, How Bitter the Tale of Love: The Changing Measure of Leisure and Pleasure in Early Modern Istanbul’ in Medieval and Early Modern Performance in the Eastern Mediterranean, ed. by Arzu Öztürkmenand Evelyn Birge Vitz, lmems 20 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2014).

2Mark Hay. ‘In Istanbul, Drinking Coffee in Public Was Once Punishable by Death.’Atlas Obscura, May 22, 2018. https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/was-coffee-ever-illegal

3 Samuel Hahnemann, The Lesser Writings Of Samuel Hahnemann, ed. and trans. R.E. Dudgeon. New York: William Radde, 1852. Pg. 392.

4 Maria Letícia Galluzzi Bizzo et al. ‘Highlights in the History of Coffee Science Related to Health.’ Science Direct, 7 November 2014. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780124095175000024

5 Joseph Kim et al. ‘Safest Roasting Times of Coffee To Reduce Carcinogenicity.’ PubMed, 1 June 2022. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35226750/#:~:text=Abstract,or%20pesticides%2C%20by%20burning%20off.

6 Alice Nguyen. ‘Bitter Origins: Labor Exploitation in Coffee Production.’ Borgen Project, 24 September, 2020. https://borgenproject.org/labor-exploitation-in-coffee-production/

7 Brian Stoffel. ‘Urban Elites, Organic Farming & The Hypocrisy of No Skin-In-The-Game’. 14 June, 2017.

https://medium.com/@stoffel.brian/urban-elites-organic-farming-the-hypocrisy-of-no-skin-in-the-game-b9f95b655686

8 Mark Fisher. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Oregon: Zero Books,2009. Pg. 18-19.

9 David Hoffmann. Medical Herbalism. Vermont: Healing Art Press, 2003. Pg. 519.

10 Ibid, pg. 124.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid, pg. 365.

13 Jan Scholten. ‘Coffea Arabica.’ QJURE (undated publication). https://qjure.com/remedy/coffea-arabica-2/

Illustrations/Images:

- Illustration: Novel “Coffee: From Plantation to Cup. A Brief History of Coffee Production and Consumption” 1881 [x]

- Photos provided by Serena Mor

Old Fence Rows and Buckthorn

Spring is Ever Drawing Nearer

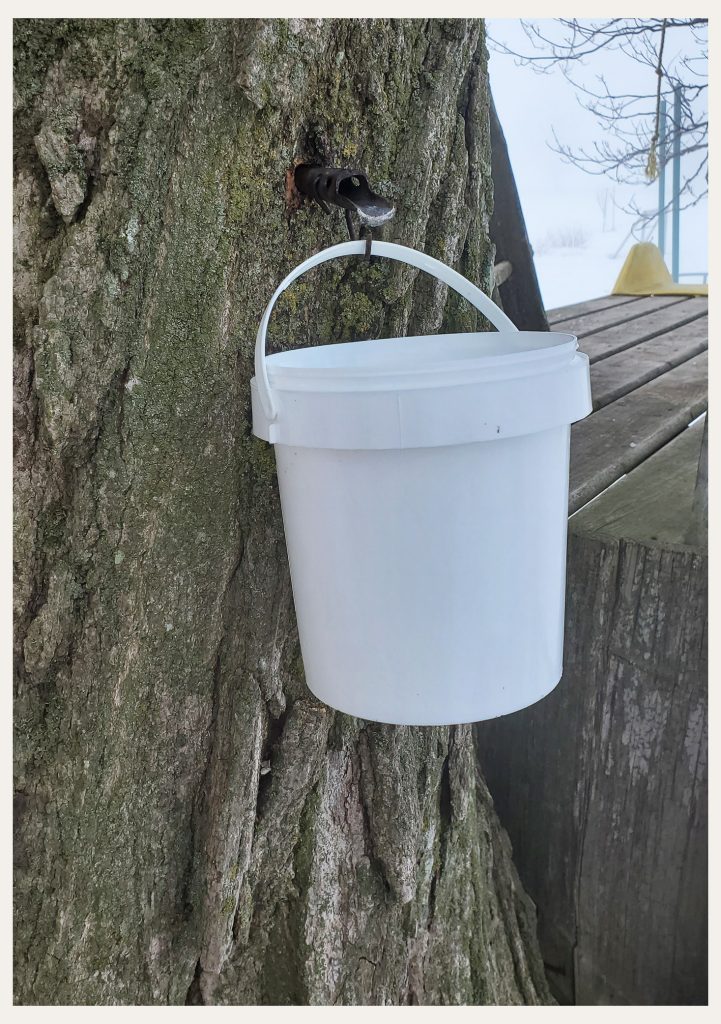

My fingers are itching to be in the earth once more – to sow and plant — bringing me into a deeper connection with the Earth once more. Our seeds have all been delivered and our trees ordered, and we are already busy here on the farm. The sugar shack is getting a new wind break and the chainsaw is sharpened and ready to go. With the snows melted and frost still in the ground it is the perfect time of year to work away at controlling the invasive Buckthorn.

As many of you know, besides being a clinical herbalist, educator and tea blender extraordinaire (a tea nut to some), we are a botanical sanctuary member of United Plant Savers. Gifting back to the Earth, thankful for all she has gifted us, especially plant medicine. So, we have been busy planting and rewilding for over thirty years now. Our goal is to plant as many endangered and native medicinal plants and trees as we can each spring and fall.

Over the years, we have had a few comments about the non-native species growing and thriving on the farm, people encouraging me to consider digging them all out, eradicate the invasive species from the land.

(Invasive species: “An organism that is not indigenous, or native, to a particular area.”)

This is easy to say for a person who is not doing the ‘work’ or not possessing a strong love for all who grow and live on these one hundred acres of land. Do we cut down non-native trees, who’s limbs hold nests of baby birds? Do I pluck every Plantain plant from the land? Do we dig up the lilacs brought with the pioneers, that still grace this farmstead — reminders of days gone by? What about her fragrant blossoms that the pollinators seek out each spring? Think about the connection they have already formed to this land.

What about the invasive species that take over an area and swallow up what was there before? These I am trying my best to keep in check and harvest freely for medicine — Phragmites and Garlic Mustard, recently appearing. But Buckthorn is a different story – she has literally kept me awake at night – how do I handle this undesirable invasive small tree?

Description of Buckthorn:

Buckthorn’s main stem is erect, with bark smooth, of a blackish-brown colour, on the twigs ash-coloured. The smaller branches generally terminate in a stout thorn, giving it the name Buckthorn. There are many older names by which this shrub has been known: Waythorn and Highwaythorn. The leaves grow in small bunches, mostly opposite. They are egg-shaped and toothed on the edges, small greenish-yellow flowers are produced, which are followed by globular berries about the size of a pea, black and shining when ripe, and each containing four hard, dark-brown seeds.

Medicinal Action and Uses of Buckthorn

Laxative and cathartic.

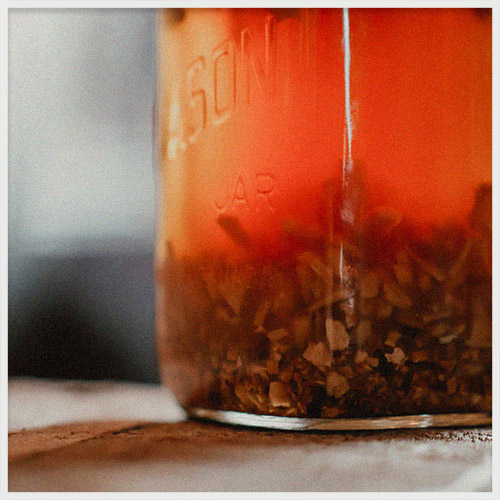

The berries are used medicinally, collected when ripe and made into a syrup of Buckthorn, which was used as an aperient drink.

Until late in the nineteenth century, syrup of Buckthorn was a most favourite remedy, used as a children’s laxative, but its action was so severe that, as time went on, the medicine was discarded. It is now used almost exclusively in veterinary practice only, being commonly prescribed for dogs, with equal parts of castor oil as an occasional purgative.

Nature’s Wildlife Highway

Buckthorn was brought here with the European settlers as an ornamental bush and to line fencerows. Keeping livestock in and to serve as much needed windbreaks for the newly cleared land. Some people may only see Buckthorn when they look at these old hedgerows, but there, amongst their midst, if you look much deeper you will see the Birch, Wild Apple trees, Maples, Mountain Ash, Basswood, Aspen, Puff balls, Morels and blankets of our beloved woodland flower, the Trout Lily – which takes over seven years to receive her first bloom!

The hedgerows on our farm are over one hundred and twenty-five years old, deep within the bushes and trees are the remains of old rotting cedar zig zag rail fences, that once marked the property boundaries. These rails now offering homes for small critters and insects, slowly decomposing and feeding the soil, and nurturing the surrounding plant life. These fencerows provide wildlife with shelter and food, and well used trails for safe travel. Connecting the travelers to other fence rows and more trails. We can’t forget the help these hedgerows gift our pollinators as well, with over thirty Wild Apple Trees — all a blossom in the spring and a buzz with life. Providing rich pollen and nectar that our bees use for nutritious food and to make their honey. Many of these old fencerows are being cleared on neighbouring farms. Cleared for more workable land and giving the huge farm equipment of today more room to maneuver with ease. Saving the farmer’s valuable time, but at what cost to our wildlife?

Do I dare disturb this delicate ecosystem? Do I disturb the hidden trails within – taking the safety from the Deer, Coyote, Fox, Wild Turkey, Lynx, Fisher, Bear, and many other creatures who frequent these paths. Buckthorn has been a crucial part of the hedgerow, nurturing the young trees and plants. With connections like these the decision is easy, my intuition has always known, the Buckthorn filled fencerows will NOT be disturbed in any way.

This is my heartfelt commitment to this land.

“Look deep into nature, and then you will understand everything better.”

~ Hans Christian Andersen

Photos Provided by Serena Mor

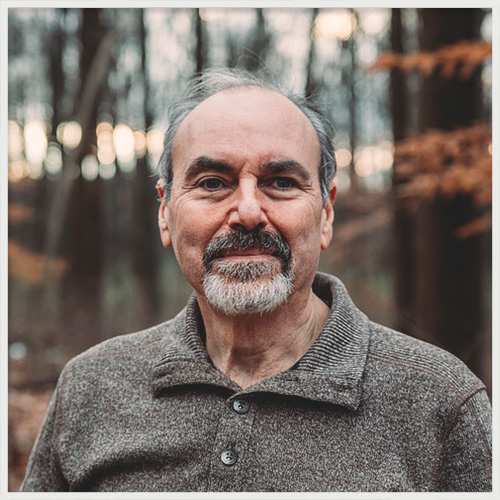

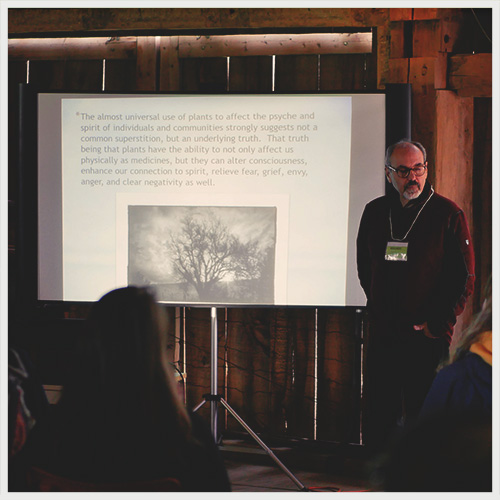

An Interview with David Winston

This interview was conducted as part of Everything Herbal’s ‘Herbal Elders’ series. This series seeks to honour and explore the unique contributions of longstanding members of the herbal medicine community in Canada, as well as abroad.

This interview was originally conducted with Nick Faunus, Penelope Beaudrow and Victor Cirone, in July, 2022.

Reciprocity in herbal medicine

Everything Herbal: I’d like to begin our discussion by considering the place of reciprocity in herbal medicine. What can you tell us about this?

David Winston: Let me start off with a story and introduction. This year I’ll have been studying herbal medicine for 53 years. I started studying herbal medicine in 1969 and at the time all of my friends were interested in one herb, and I was interested in all of the others. Fascinating how today the interest in that one herb has grown tremendously, but I’m still primarily interested in all of the other ones. In 1969 there were no real herb schools, it was hard to learn about herbal medicine. People would say to me what do you do? I would say I’m an herbalist and people would look at me like I was an alien from another planet coming to abduct them. Why would you waste your time with something people did 100 years ago? I fell in love with plants and herbs, with being able to walk out in the woods and the fields and find medicinal and edible plants. My early learning came from a number of sources. Some of it came from books, I would read any book I could find on the topic, and at the time there weren’t that many. One of my first books was ‘Stalking the Wild Asparagus’ and then ‘Stalking the Healthful Herbs’ [both titles by Euell Gibbons] and ‘Back to Eden’ by Jethro Kloss. In reading these books, I was being handed knowledge of the generations, knowledge of our ancestors. And then I started looking for people that I could learn from. And it was difficult. I took a couple of classes from Dr. Christoper probably in the early to mid 70s. One of my friend’s fathers came to America from Germany and was really into organic gardening and farming, which he taught me. I had another friend in high school whose mother had studied Chinese cooking. I knew how to bake and we taught each other. This is one of the things that initially peaked my interest in Chinese herbs, learning to use them in a culinary way.

Reciprocity was built in – the fact that much of what I learned early on was not necessarily from a school where I was paying for the information. I remember one time we went to the World’s Fair in Montreal when I was a kid. My parents decided we were going to go for a little vacation up into Northern Quebec. It was a memorable trip. This was at a time when there was a fair amount of anti-English sentiment, which we didn’t know about until we arrived there. My mother did speak a little bit of high school French, but not Quebecois. Most of the time we would go into places and they wouldn’t talk to us. It wasn’t a question of whether they understood English or not, because as soon as they recognized we were English speakers they ignored us entirely, like we weren’t even there. We went into this one store, a general store, and they had horehound candies. I had never had horehound before, but I had read about it. So I had to get them. I put one in my mouth and within 10 seconds I spit it out, it was the most disgusting thing I had ever tasted in my life, or so I had thought at that moment. Interestingly enough, an hour later I wanted to try another, which I was able to keep in my mouth for 30 seconds. And by the end of the day I liked them. It was a gradual process of getting acclimated to the flavour. The guy at the counter noticed I bought these and was trying them, and he said to me in English, ‘are you interested in plants?’ I told him that yes, I was deeply fascinated. He started telling me about his favourite herb, a plant he called black snakeroot. I had no idea what it was he was talking about, he didn’t know any Latin binomials. He had a little bit of this herb, let me smell it and gave me some to taste. Many years later I realized that what he called black snakeroot I would call wild ginger, Asarum canadense. It was one of those experiences of recognition and generosity, facilitated by the plants. This happened even though I spoke English and he primarily spoke French. What made the breakthrough was plants.

I feel so fortunate to have been studying herbs for 53 years, and to have been in clinical practice for 45 years. I’ve got to spend almost my entire life in this community of people who love plants. For a very long time I thought I was the only herbalist in the entire Eastern US. It turns out I was wrong, but the majority of the other herbalists who I later found out about were often folk herbalists in rural communities, well known in their own communities but not beyond that. People like Evelyn Snook in central Pennsylvania, or Catfish Gray in Virginia, or Tommy Bass in Alabama. There were other herbalists too, they just weren’t particularly well known. I grew up in Maryland but we had moved to New Jersey, and there was a woman in Rahway, NJ, Henrietta Diers Rau, who I never got to meet but I found her wonderful but somewhat obscure book, ‘Nature’s Aid’ in the library. Henrietta trained at the British School of Phytotherapy in the UK, she was a practicing herbalist, not very far from where I lived. Some years later, in 1981, the first major US herb conference took place in Breitenbush Oregon, organized by Rosemary Gladstar and California School of Herbal Studies. At that time I was the only herbalist there from east of the Mississippi river. I remember sitting in this large room, in a semi-circle with 69 other people, sitting on the floor, looking at all these faces and realizing: these are my people. It was such an incredible experience to feel a part of something.

“…So many herbalists live truly inspired lives”

If we go back 40 or 50 years, being a herbalist was not something that was widely known, appreciated, or in any way accepted. If you told your high school guidance counsellor that you wanted to become a herbalist, they would have looked at you like you had lost your mind. The reality is that people who took up this work were very isolated, but eventually as we got to know each other, we found out there was an amazing community of creative, curious and interesting people working with plant medicine. So many people in the herbal community were multifaceted and amazingly talented. Our herbal elders, some of whom are no longer with us. Michal Moore, for instance – he was a classically trained musician, and performed on wind instruments in the LA symphony orchestra. Michael Tierra is a concert pianist. Jillian Stansbury is a polymath, she is brilliant in so many ways; she is a musician with an incredible voice, and for fun in her spare time she studies things like quantum physics. It is such an interesting group of people: poets, artists, musicians, as well as herbalists, and I think that speaks to the heart of many herbalists, to the fact that so many herbalists live truly inspired lives. Nobody gets into herbal medicine because they think they are going to become rich and famous. That’s not the motivation. There are people who become well known and make a good living, but that is not the underlying motivation. To a great degree, people fall in love with plants and with the idea of helping others, and that is the real motivation.

Even though I’m not in full time practice anymore I still see patients. I haven’t charged people for helping them since sometime in the 1980s. I just help people. It seemed it was not right to charge people to make money off of their suffering. I’m not trying to suggest that it is wrong for others to charge for their services. My income comes from teaching, writing books, consulting with physicians and industry. When somebody comes to me and they say ‘I need help’, I just help them. For me that is a big part of reciprocity. So much of what I have learned over half a century was shared with me freely and I love sharing it with other people. Whenever I can, and whenever people are interested I’m always happy to share what I have learned. You know the old expression: we stand on the shoulders of giants. It’s true. So much of what I know comes from traditional Chinese medicine, from Southeastern traditions in America, the Eclectics, the Physiomedicalists, from the practices of Ayurveda and Unani-tibb. These traditions are 100s or even thousands of years old. They all inform what I do and what every other herbalist does. Nobody discovered all of the things that St. John’s wort can do by themselves. It has been a gradual process of disclosure taking place over millennia. As we use herbs in clinical practice, we gain unique insights and share them and our collective knowledge just continues to grow. This too is reciprocity. I see so much of this in the herbal community: reciprocity, generosity, creativity. And those are wonderful things to have as a foundation for a community of people who are in most cases trying to make a difference in the world by making people’s lives better.

Accomplishments in the world of herbal medicine

Everything Herbal: What would you identify as some of your major accomplishments in the world of herbal medicine?

David Winston: The greatest thing that I personally have done as a herbalist is in the area of education. As a practitioner, there are a lot of people I have worked with and helped. Sometimes people say: ‘you’re a healer.’ I’m not, the herbs are the healers, the Creator is the healer, I’m not a healer. At best, I’m an educator. Whether I’m educating on a one to one basis in my role as a clinician or educating students about the wonders of herbal medicine, it’s a deeply fulfilling role. I may be giving an herb walk and sharing with people who may have never been exposed to herbal medicine before, or lecturing to my two year herb studies program, where thousands of people have studied. The program is designed to teach people to become clinical herbalists. Half of the students who come into this program are already medical professionals, MDs, NDs, DOs, nurse practitioners, acupuncturists, veterinarians, and other health care professionals. The other half of my students are people who have been self studying herbal medicine for years or even decades and they really want to improve their skill level so that they can help people in more profound ways. Adding herbs to your toolbox, so to speak, makes a huge difference. It’s not that herbs can do everything – they can’t. But where herbal medicine is strong tends to be where orthodox medicine is weak and vice versa. When I say herbal medicine, understand that in my view herbs are not foundational. What do I mean by that? The foundations of health are a healthy diet, adequate good quality sleep, exercise, healthy lifestyle choices, and stress reduction. Those are the foundations of health. Any herbalist or any practitioner of any sort that is not working with all of those things is missing the boat. Nobody ever became sick because of St. John’s wort deficiency. The idea is that we want to do everything we can to help people. We start with the foundations of health, and when we get to therapeutic modalities herbal medicine is incredibly useful. Most herbs are relatively nontoxic, there is a fairly low rate of clinically significant adverse effects especially if you know how to use herbs appropriately.

“It is more important to know the person who has the disease, than the disease the person has” – Hippocrates

In my first two year herb studies program I had two students. That was in 1981. I was thrilled that anybody else wanted to learn about medicinal plants. Today we have students from all over the world. My goal in teaching people is not to teach them to be good herbalists; my goal is to teach them to be great herbalists. When I say great I don’t mean as a comparison to someone else, I mean each person in their own unique way. Each of us is capable of greatness based on our unique knowledge, intelligence, skillset, passion, creativity; each of us has the ability to take this information and do unique and wonderful things with it. But I also believe that if you really want to be a great herbalist, then there are a few things you have to understand and the first thing is to stop focusing on treating disease. Hippocrates is believed to have said more than 2000 years ago: “it is more important to know the person who has the disease, than the disease the person has”. He was right then and he’s right now. What he means by that is if you have 5 people, all diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, the treatment for each will be based upon their unique requirements as individuals. From an orthodox medical perspective the treatment for a given disease seen in different individuals is often the same. As an herbalist, I look at 5 unique people. Yes they all have rheumatoid arthritis, some are female, some are male (hormonally speaking), some are old and some are young, some have underlying GI issues, some have circulatory issues, some have cardiovascular issues, and the more you can treat the person who has the disease, the more effective your protocols are by far. If you have somebody with bacterial meningitis, don’t call the herbalist, reiki healer or chiropractor. You want them in the hospital with iv antibiotics. It is not about creating a dichotomy between orthodox and complementary medicine. They both have their strengths and weaknesses. The key is helping students to understand how they can most effectively help people.

46 years ago I was introduced to the concept of energetics by one of my early teachers who in my opinion is one of the great herbalists of the 20th century: William LeSassier. William is the person who introduced me to herbal and human energetics, which allows the practitioner to match specific herbs to the person. When you focus on the disease, you are missing out on the energetics and the constitution of the patient, which is required if you are to treat the person. William also introduced me to Chinese medicine and Chinese herbs, as well as a lot of obscure western herbs like evening primrose. Everybody who is reading this is probably is saying ‘evening primrose seed oil, I know about that.’ But I’m not talking about that, which I don’t think is even all that useful. I’m talking about the herb Evening Primrose (Oenothera biennis), the leaf, flower or root bark. It is a common native weedy plant, it is an incredible medicine used for things like GI-based depression and inflammatory bowel disease, it’s a wonderful medicine that almost nobody knows about. I credit William again with changing my mind and my entire direction in herbal medicine. Before what I had encountered was along the lines of: this herb is good for headaches, this herb is good for depression, etc. You see this all of the time with these little soundbites of information about herbal medicine that get circulated in books, classes and the internet. For example, St. John’s wort is the depression herb, Saw Palmetto is the prostate herb, or Black Cohosh is the menopause herb. There is one problem with each of those statements: they are wrong, wrong and wrong.

Take St. John’s wort: when I teach on the differential treatment of depression and anxiety, we differentiate more than 14 types of depression based on the underlying pathophysiology. When you treat a person who is depressed, you need to understand what is actually causing the depression. Is it GI-based depression, inflammation-induced depression, old age- induced depression, blood sugar dysregulation-induced depression? The studies show that most pharmaceutical medications like SSRIs and SNRIs work about 40% of the time. St John’s wort also works about 40% of the time if you just give it for the disease entity depression. But if you actually treat the person who is depressed, I can say from my own clinical practice (there are no studies on this) 60 – 65% of my patients with mild to moderate depression have very significant improvements, even to the point where they don’t feel they are depressed at all anymore. This is huge when compared to 40%. Is it perfect? No, but the point is that we have a significant improvement when we are treating the person rather than the disease.

“…That we have helped to teach people how to be great herbalists, is something I’m very proud of.”

For me I think the accomplishment I am most proud of is to be able to look around and see a much bigger herbal community than existed when I first started. People who have been part of my programs are a piece of that, and to know that we have spread that information, that we have spread that knowledge, that we have helped to teach people how to be great herbalists, is something I’m very proud of. Today I look around the world and there are people who have graduated from my program who have their own schools, who are well known herbalists that have written many books, who have these incredible practices. Of course it is not just because of my program that they accomplished these things, it was just a piece of their development. But the fact that I can help people with that one piece to me is a blessing. It makes me very proud to be a part of this community and to continue to pass on what I have learned, to share it and have our traditions continue.

“In the US we spend more money per capita on healthcare than any other country in the world”

Some years ago I was the keynote speaker for a conference called the Florida Herb Conference, organized by Emily Ruff, a wonderful herbalist. I called my speech ‘I Have a Dream.’ I started off by saying ‘you’ve heard these words before by someone far more eloquent than I, but I have a dream too, and my dream is that within my lifetime I hope to see a time where almost every mom, dad, grandmother and grandfather knows basic kitchen herbalism for their family, where there are community herbalists in every community and clinical herbalists available in any clinical setting.’ Why? I believe without a shadow of a doubt, and I’m talking now about the US, (in Canada things are a bit different) in the US we spend more money per capita on healthcare than any other country in the world yet we have worse health outcomes. We are behind every developed country when it comes to infant mortality and life expectancy. We are close to the top when it comes to obesity and cancer, but in all of the health measures that you want to be good at, there are many underdeveloped countries that have much better numbers and outcomes than we do. I believe that really well done herbal medicine can help us create a sustainable practice of medicine not only in the US but around the world. There are countries like India, China, Japan, even Germany where herbal medicine is part of mainstream medicine and it allows them to have a more effective medical system with fewer adverse effects and a greater number of options. That’s my dream. That’s my goal. To make this not alternative, but a part of the mainstream, not just mainstream medicine but mainstream understanding and knowledge. I hope that at some point everybody knows basic herbs to use for common ailments. Most people already know that if you are constipated you can take prune juice or that you can use aloe for a burn. There are lots of things like that that people could learn and use at home, thereby preventing for example the unnecessary use of antibiotics. Antibiotic resistance is a huge problem today. How many times could we give somebody antibacterial herbs for a UTI and thereby avoid having to use antibiotics altogether. How many times do we see people being given antibiotics when they have a viral infection and they don’t work at all? Yet we have herbs that would be perfectly appropriate in that situation. Are herbs the answer to everything? Absolutely not. Are they an answer that can help us to create a better practice of medicine, one that is better for the planet and better for the people and animals on the planet? Without a doubt.

“As a clinician one of the greatest gifts that you can give yourself is to keep an open mind.”

Everything Herbal: I’ve been fortunate to go to many herbal conferences over the years and have heard so many speakers. Out of all the speakers I have listened to, I can still see you on our stage at the Restorative Medicine Conference. I was in the front row doing the introductions and you opened for us. You sang a song, and even though I had no idea what you were singing, it penetrated my soul and made me cry instantly. To me in that moment, and even now reflecting back after all of these years, it was a profound healing experience. I still even get emotional about it because I have no idea what happened in that moment, but I know that something happened. You were the portal for something awe inspiring to come through, and it was a great gift.

David Winston: As I said earlier, I think that the plants are the true healers but many people in the herbal world have gifts that go beyond herbal knowledge. Many are inspiring, wise, and stewards of the green world. In addition to being an herbalist, I write poetry, I sing, I garden and love photography. These things bring me pleasure and help me to see the world in a different way and express myself creatively. I always wished I was better at visual arts. Unfortunately I’m not a very good artist, although both of my parents were very good artists. I have some significant visual, hand/eye coordination issues. I was born severely visually impaired and I didn’t actually see until I was about 18 months old. I had 3 surgeries on my eyes by the time I was 5. There are certain things that I just don’t do as well as most people do. When I was a child there was no diagnosis of dyslexia, or ADHD, although I would have been diagnosed with both if I was born 15 years later. People think of them as disabilities, and they are challenges for sure. But they also bring unusual strengths and skills if you are fortunate enough to have the necessary help navigating the differences. I was talking about this before when I talked about being great in our own unique ways. I don’t consider myself great in any particular way but I am striving to be the best that I possibly can be in every single thing that I do. Now obviously I fail more than I succeed but you keep trying, you keep trying to grow and become a better person, clinician, parent, friend or partner.

As a clinician one of the greatest gifts that you can give yourself is to keep an open mind. I always tell my students the worst disease a practitioner can get is what I call “hardening of the mind”, where you start to believe that everything you know and think is true. I am partially kidding when I say this, but I always tell people after 53 years of studying herbal medicine I now feel comfortable calling myself an advanced beginner. Why? It doesn’t matter how much you know, it is still a fraction of what there is to know. You always want to stay open to the process of continuing to learn. This is true for anybody, whether an auto mechanic, a scientist, a farmer, a physician, an herbalist or an artist. It is openness to creativity, to new ways of seeing, thinking or being that allows us to grow professionally and as human beings. How many examples do we have of musicians who become famous for a certain style and their next album comes out and its totally different and their fans don’t like it. But as an artist, there is something that pushes you to grow and experiment. To stay stagnant and just keep doing the same thing over and over and over again doesn’t serve that purpose and ultimately doesn’t serve the art. As an herbalist or as a clinician you have to stay open minded to the fact that everything you believe is true is subject to change. That doesn’t mean it will change, but it could. When we get dogmatic and when we start allowing ourselves to be put up on a pedestal, we are in dangerous territory. If you are up on a pedestal and everybody is looking up at you, invariably you are looking down, its an uncomfortable place to be. Something about human nature is that while people love putting others up on pedestals, they also love tearing them down.

“… Recognize that the plants are the healers.”

It is important to stay humble, to recognize that the plants are the healers. Art, music and creativity are also great healing forces. So is vulnerability. Recently in class a student asked a question and it was about somebody going through a really hard time. I didn’t say to them ‘oh you should do this and that’; instead, I allowed the experience that was shared to touch me, just like that song touched you. The experience of suffering that was related in class touched me deeply and reminded me of an experience in my own life. It was a very humbling experience; being able to share vulnerability and fragility with others allows people to recognize and connect in to their own pain, their own suffering, their own fears, their own doubts. When we can do this, we begin to recognize that we are not alone in our sufferings, and not alone in the world. In any traditional form of medicine, there is no separation of body, mind and spirit. Of course, there are times when you have a simple wart and I don’t need to know what’s going on with you emotionally. I can simply say, ‘here try some celandine, put it on twice a day’ and more often than not the wart will disappear. But if we are talking about more serious health issues like depression, anxiety, autoimmune disease, cardiovascular disease, all of these conditions don’t just affect the body, they also affect the mind, the soul and spirit too. All of these levels are deeply interconnected, they are all part of the same organism.

This is also where complementary medicine can fall short. There was a diagram created by Kenneth Pelletier in the 70s of three interconnected circles labeled body, mind, and spirit. That is supposed to represent holism. There is only one problem with that: it is not big enough. If you put a big circle around those three interconnected circles, that circle is family. Then there is another even bigger circle around that, and that’s community. And then there is yet another circle around that, and depending on what name you want to give it, that’s God, the Creator, Nature, Gaia, whatever concept you want to put in there. What the body/mind/spirit level of the diagram recognizes is that we are interconnected within ourselves, but what it fails to recognize is that we are also connected to everything else, to everything outside of ourselves. When I teach my class on depression, one of the things I always tell people about depression is that it can be a learned behaviour. If you grew up in a household where one of your parents was chronically depressed you stand a 50% chance of being chronically depressed yourself. If you grew up in a household where both of your parents were chronically depressed you have about a 100% chance of being chronically depressed. As an infant and young child you don’t know what is healthy behaviour and how things in the world can or should work. Whatever behaviour that is modelled for you becomes your norm. If the people around you are always depressed, always anxious then that is what you come to believe is normal and desirable.

“To feel that you have a place in the world, to feel connected is essential to health and wellbeing.”

There is also a part of the brain known as the mirror neuron network. If, for example, your significant other is chronically depressed or anxious, the chances of you becoming chronically depressed or anxious skyrockets. Why? Because this part of the brain which allows us to feel empathy, sympathy and connection to others, triggers deep feelings and emotions in us that are indistinguishable from our actual emotions. For most of us when we see somebody who is suffering and we feel it, not just ‘oh that’s too bad’, but when you really feel it ‘oh my god thats terrible’, you want to help and do something. That is the part of the brain that mirrors the behaviours of others, and if you are in a relationship or even living in a place where other people are experiencing those things on a regular basis, it is very hard for you not to respond and get pulled into that mindset, whether it is anxiety or depression or hopelessness. We are deeply affected by others, and in many indigenous traditions if somebody is ill you don’t just treat that person, you treat their entire family. The next circle after family is community, and so many of us no longer live in functional communities. We are isolated and separated, and this causes major issues for human beings, who are innately tribal. By using the word ‘tribal’ I do not necessarily mean a native nation, although that is certainly tribal. I certainly don’t mean the terrible tribalism that we have in the US: red vs blue, liberal vs conservative, etc. That is tribalism at its worst. What I mean is that we feel the need to belong. Unfortunately that seems to be one of the appeals of so many of these hate groups that are out there now. You have people who don’t feel like they belong anyplace, who feel like outcasts and feel scorned and belittled by society. Often, they find acceptance and comradery in such movements and they get caught up in a group that is bounded by hatred. To feel that you have a place in the world, to feel connected is essential to health and wellbeing. I talked about it earlier when I was describing sitting in a room with 69 other herbalists at a young age and feeling that I had finally found my people. Being able to find others who accept us for who we are, and participating in a functional, healthy community; this is unfortunately so rare in today’s world.

“You are part of something bigger than yourself”

The last circle, relating to one’s relationship to a higher power (again, whatever name and concept you have of this is fine), helps us to recognize that we are a small part of something much greater than ourselves, something that pulls us out of our ego, pulls us out of our fear, doubt, isolation, separation and out of our belief that the world begins when we are born and ends when we die. This perspective reminds us that yes, each and every one of us is sacred and blessed and yet each one of us is a speck of dust. We are both magnificent and insignificant at the same time.

This is the importance of having a spiritual practice, whether you have a religion or not. The connection to a higher power is the essential piece. If you don’t believe in an entity, you can achieve the same thing through Nature, Gaia, it doesn’t matter, as long as you believe you are part of something bigger than yourself. That is a really useful and helpful orientation for human beings to have; it is arguably what allows us to become human beings in the first place. If you ever go some place where there is almost zero light pollution, and I’ve been to places like this in the mountains of North Carolina or in parts of Canada, New Mexico, Maine Ireland and Costa Rica, and you look at the night sky it can be breathtaking. Instead of seeing a few bright stars or planets, you see the entire milky way. Sadly many people have not had this experience today. When you look up at such a sky it is magnificent, you enter into a state of awe. It makes you feel so small but at the same time connected to something so vast. To me that is the power of healing, those moments that literally take your breath away where you’re just in awe that the world is so magnificent, so beautiful. For many of us that experience is so far away from our daily lives, and we lose sight of it, we lose sight of the joy and the newness and the discovery and the wonder of the world that we were born with as children. For many people today, the world is not a place of wonder. It is a place of fear, hurt, prejudice, or inhumanity. I think that herbs, nature, meaningful ritual, forgiveness, compassion and love can contribute to the healing this core wound of disconnection that many of us suffer from today.

“Originally I was going to be a farmer…”

When I was in high school I used to have an organic farm. It started off as a 20 or 30 by 80 foot plot and eventually I got more land down the road. I had two acres and a roadside stand where I sold organic vegetables in the summer, in the late 60s and early 70s. Originally I was going to be a farmer, I was growing herbs and vegetables, and the one thing I didn’t grow was flowers. I thought who cares about flowers. Today I realize I was mistaken. While I still grow many herbs and vegetables, today I love flowers. And three of my favourites are fragrant roses, irises, and peonies. The irises I grow are old fashioned fragrant irises. The modern ones often have no odour, but the old varieties are really fragrant and they almost smell like a combination of cinnamon and bubble gum, a very unusual combination. Every year, when the irises start blooming I go out every single day and stick my nose in those flowers and just inhale deeply. Think of it as primitive aromatherapy. When the peonies are in flower, I go out there and I smell them too. The roses start blooming before any of the others and continue blooming in through the autumn. When I go out and smell these flowers I am so uplifted by their odours. Yes the night sky in a place where there is no light pollution is spectacular, but smelling a fragrant rose is also magnificent. Smelling one of those fragrant irises is magnificent. Magnificent things, healing things can be huge things that literally stop you in your tracks, as well as little things that for a moment bring you back to a place before you were weighed down with all of your worries, to a simpler, better place of healing.

Let’s talk a bit more about the integration of herbal medicine with the conventional medical system…