The Story of the Haiti Naturopathic Clinic: An Interview with Julia Graves

Emergency Medicine and Disaster Relief in Haiti

Welcome to an interview with Julia Graves! This interview was conducted by Victor Cirone with photos used with permission from Julia.

This interview was conducted on May 27th, 2021, before the assassination of Haitian president Jovenel Moïse, and before the recent, devastating earthquake of August 18th. Julia is currently coordinating fundraising efforts for the earthquake victims and to help support the vital work that is carried out by the disaster relief clinic that is the focus of this interview. To find out more about how you can help, and for updates on the current situation in Haiti, please see the clinic website and subscribe to their newsletter: haitinaturalclinic.org

Victor: What can you tell us about the trajectory of your life and work, and specifically how you got to where you are working in Haiti?

Julia: The moment of us starting the clinic in Haiti is, in a way, the culmination of my life up until that point. I was raised by an herbalist mother and an orthopedic surgeon father, so I’ve worked between the paradigms of conventional medicine and plant healing. Then I trained four years of medical school and as a psychotherapist, and I always continued to work with plants and natural healing. I had at that point, when the great earthquake struck Haiti, at least 30 years of experience of working with herbs, flower essences, aromatherapy, and homeopathy. Because it was my partner’s [Jacquelin Jinpa Guiteau] home, and his father got injured in the earthquake, it became very compelling to go and help. If you remember, it was an underwater earthquake, so the epicenter was off the coast, under the ocean, about 3km out – Jinpa’s parents’ home was exactly 3km on the shore. His father fell and injured his shoulder, but we couldn’t send him any help, and we couldn’t go there because all flights had been stopped. As soon as the first airplanes were allowed back into Haiti, he went to just see the situation and said, ‘if I go I would like to help people who are in need of medical care, could you put something together for me as a first aid kit?’ Which is what I did. 48 hours later he called me and asked if I could join him immediately (I was in France) and bring $10000 in donated cash and two suitcases more full of natural medical supplies. 24 hours later I was in New York to pick up the cash and more than 2 suitcases worth of donated supplies, and in 48 hours I was in Haiti, in the rubble. And that’s how it all started.

I do want to add one thing: all of my experience went into a precise concept of the clinic. I had a very clear idea that homeopathy would be great: it’s tiny, it’s light, you can give one pellet per person, and so with a tiny amount you can treat the masses. If need be, you can succuss more, you can dilute and potentize more. Similarly with essential oils, you can do a lot with very little. Although I’m very much an herbalist, I was very clear that trying to stuff dried herbs into your suitcase, or bottles and bottles of tinctures is just not ideal for an emergency situation. So, based on my background, I clearly favored homeopathics and essential oils and that was the bulk of what I brought initially.

V: Most of the audience who will be reading this interview will have more of a background in herbal medicine than they will in homeopathy. At least in North America, there is still a fairly strong divide between herbal medicine and homeopathy. There are some herbalists that I’ve encountered who have even expressed suspicion or outright disdain for homeopathy, claiming that there’s no way it has any real efficacy, that it lacks scientific legitimacy, etc. Can you tell us more about the protocols that are used in the clinic and why homeopathy is so important to the work you do there, beyond how easy it is to transport homeopathic remedies and how cost effective they are?

J: Let me first talk a little about why I brought essential oils. First of all, we as herbalists quite rightfully assume that we can use the essential oil of chamomile in a similar way to chamomile tea or tincture. It is very easy to make that transition when you are faced with an emergency situation where you can’t put a lot into your suitcase, and so, take a variety of essential oils. The other thing is that essential oils are highly antiseptic – they kill everything, as it were: antibacterial, antiviral, antifungal, antiparasitic. Most essential oils are the first three, and some also end up being antiparasitic. When we reached Haiti, the streets were so cracked open, everything had fallen to pieces, and the stench in the air of the rotting bodies was just unfathomable. In such a situation, you want something that is very, very ‘anti-everything.’ On top of that, to purify the air from germs, you want to use essential oils. You can spritz them, you can leave them out, and you can literally disinfect the air around you in that way. It was very good for us as healers to be in a situation like that where we could handle substances that served to protect us from disease. We still got horrific diarrhea, but there wasn’t even anything close to clean water available at that point.

For me, I can understand that most herbalists cannot understand homeopathy. There’s an element of mystery to it. You can’t understand how it can possibly work. I trained very young in homeopathy, when I was 19. By the time I went to Haiti I had tons of experience using homeopathy in emergency situations. I had lived in India for 3 years where I trained at the Tibetan monastery that is next to the Dalai Lama’s palace in Dharamshala, and there is no medical care for the little boy monks there. So I was treating a lot of these boy monks and people in India who were in very desperate situations, including lots of animals and lots of babies, so I knew for sure that you don’t have to believe in homeopathy for it to work. I had treated people who can’t speak because they are babies, I treated animals, people who can’t speak the same language as me, who have no understanding of what I’m putting into their mouths, and I had seen incredible results in very poor hygiene type of environments. I had complete confidence, I had my baptism by fire, what the horse rider experiences when they fall off the horse for the first time – I had already been through that. At the point I came to Haiti nobody could have talked me into the idea that homeopathy is not effective. And I was already very experienced treating myself and others, so for me it was just a no brainer, especially when it comes to vulneraries, injury remedies, or things for acute and superficial issues such as disease from dirty water – diarrhea and vomiting – I had tons of experience treating that in India.

To take another common scenario we encountered in Haiti: being sick as a consequence of sleeping outside in the cold. When we got to Haiti it was March, the earthquake was in January, so everybody had been sleeping in the streets in February when it is quite cold, and we have this wonderful remedy in homeopathy called Aconite, which is also used in Chinese medicine to warm people up, for diseases from cold. There are wonderful homeopathic remedies from the Artemesia genus of plants, which are also used in herbalism, for the treatment of worms and parasites. In underdeveloped countries virtually all children have worms. We could discuss many other common scenarios and the relevance of homeopathic medicine in dealing with them. Based on my previous experience, I already knew what I was going to need and want. We had anticipated injuries, coughs and colds and the usual stuff such as malaria and yellow fever; but we hadn’t anticipated the mind-blowing amount of vaginal infections, which had nothing to do with the earthquake per se, but with poor hygiene and dirty water. And for that we then had to work out a treatment protocol.

Lastly, just to add one more reason explaining why the homeopathic approach was so great in this context, especially in the initial years, was to treat street children: You cannot give a homeless three year old who lives in the street anything herbal – a bottle will be lost almost immediately, they have zero access to potable water, let alone a fire or tea kettle so herbal teas are out, etc. I was incredibly grateful to have a reliable and powerful method where I could give the child one single dose right into their mouth and know it could cure whatever ill was at hand (worms, influenza, head trauma), with the higher potencies’ action lasting for weeks and months.1

V: I remember that in one of your previous newsletters, you talked about a traditional Haitian practitioner, a herbalist and bonesetter, and I remember that you said in that piece that the Haitian people were somewhat skeptical of working with him, that they didn’t believe that he had the healing abilities that he did. Can you talk about the attitude of the Haitian people when it comes to disease and healing generally, and about traditional Haitian healing practices in particular?

J: We literally had to start the clinic by putting a table and four chairs out. There was Jinpa on one side being one of the doctors, me on the other side being the other doctor, with a second chair for each of the patients. We immediately had 300 or more people a day, between 300 and 500. The most we could treat on a given day was 500. There was a lot of skepticism. People were desperate because there was no medical help at all available to them; you have to understand that the medical system in Haiti is such that when people can’t pay, there are zero medical services available to them. We were in the city of Port-au-Prince because the epicenter hit there. There are no wild plants there. In the Haitian countryside there is still traditional herbal medicine available. People were very skeptical of us because first of all they had very bad experiences with large organizations such as the Red Cross. There are two main things we heard over and over again: the first was that people didn’t want to stand in line and wait to be treated because, as they said very suspiciously, ‘are you going to force vaccinate us?’ and we explained that we don’t even have syringes here, everything is natural, we use plants. And the reaction then was ‘oh, then I’ll stay in line.’ So there was tremendous skepticism towards being forced vaccinated, which is part of the International Red Cross’ way of doing things, apparently.

Then they were very surprised that we actually spoke their language rather than them not being able to communicate with us at all. They liked that. The second thing that made them very gun shy, quite literally at first, was that the other organizations, even Doctors Without Boarders, usually have a building that is guarded by soldiers with machine guns. People are reluctant. They were literally looking around and scoping out the place, wondering ‘where are the soldiers with machine guns? Oh they don’t even have protection, now I feel safer waiting in line.’ The third thing that made them gun shy was that there was a practice, a very widespread practice, of dumping expired pharmaceuticals into Haiti which has been stopped since then. The government made this practice illegal and now checks expiration dates on pharmaceutical drugs coming into the country. There has also been a kind of undercover testing of non-licensed drugs in Haiti. People who were coming to the clinic kept saying ‘we get things that are expired, we go to the hospital, they give us an injection, and we get so sick.’ We heard that over and over again. So all of that was overcome the moment we said ‘no, no we only use plants and we don’t have injections’ and whatever we gave them also looked nothing like a pharmaceutical drug. That was one kind of very strong caution and mistrust we had to overcome.

And then there was the caution and mistrust that they harbored in regards to their own tradition. Of course because they have been brainwashed by modern media, education, and all of that, the herbs grandma uses are not good. We tried to role model to them that healing with plants is okay. We knew that the husband of one of the women known to Jinpa’s family was a traditional herbalist, midwife and bonesetter, all wrapped into one. We asked him to come in and do his work. We checked it out and he was really quite knowledgeable and had a lot of very helpful things that he was able to do that we couldn’t. For example, he knew exactly what kind of a poultice to use on children no older than 2 years old in order to heal inguinal hernias. We didn’t have anything like that, where you could just take a few drops of a medicine and the hernia is gone. And he was able to touch a pregnant woman’s belly and could check if she was carrying one or two babies, if they were in the right position, if everything was generally okay with the baby, the position of the placenta, if the woman needed pelvic adjustment – he could do those things that we weren’t trained for from within the traditional context and it helped people have confidence in their own traditions again. They really liked the treatment and we often overheard them when they were leaving saying ‘oh yeah I have a person like that in my neighborhood, maybe I could go see them.’ We tried to really not be like the Red Cross, which has come in from the outside totally detached from the local culture, from traditional Haitian medical thinking and understanding, from their language use and using products that come from elsewhere and were threatening. It was very important that we create an interface with the people, their culture, their language, their healing traditions. That was very much our aim.

V: Do you have cases that stand out that you’d like to share?

J: One of our cases that I love to talk about is that of a 2-month-old baby boy who was brought in to us who had been declared to be dying of yellow fever. He had been born to a 15 year old teenage mother and the bonesetter explained to us that girls like that will not bond with their baby if they see that the baby is sick, as a protection mechanism they then drop the baby, they emotionally disengage, because they want to save themselves the heartbreak from having their firstborn die. The mother had literally wandered off doing other things and left the baby in the tent camp and the warden of the camp, Marie-Lucie who is now working for the clinic, brought in the baby for treatment. She explained that the baby is dying, that the family had scraped together their last bit of money to bring him to the hospital, that the doctor diagnosed yellow fever and explained that it would cost a million so to speak for medical treatment, which they didn’t have. What happens in Haiti in such a situation is that the doctors will say ‘go on, take the baby home it will die.’

The baby was brought to us at that point and he seemed to be in a very dire condition, hanging limbs, the eyeballs turned up, and I was there with this very difficult situation, in a screaming environment with hundreds of people standing in line, tasked with being given 5 minutes to diagnose and heal a dying newborn. One of the things we use very much in the clinic as a diagnostic tool is Chinese pulse diagnosis because then you don’t need language. One of our questions for people coming to work at the clinic is: what do you know to diagnose without needing language, because you won’t be able to speak Creole or French, most likely. So, anyone doing Chinese medicine will know how hard it is to take a good pulse with a newborn. I used a technique where I took his pulse – you take the pulse with the fingertip of just one finger and it was extremely wiry, a very typical high fever/heat pulse, and I had by that time noticed that I could get really good pulse readings on newborn babies, because there were so many, by just putting the vial with the homeopathic remedy in their other hand. Because they have this reflex of holding onto everything, they just grab the vial. When I put the Aconite in his hand the pulse went down, the heat pulse signs were seriously going down. I gave him one dose of Aconite 200C, which is a very, very classical high fever remedy and within a very short time, something like a minute or two, his flapping hands came back up, the whole tonus came back to his body and – bing! – he opened his eyes. I gave the lady who had brought him a tiny bottle containing a few drops of lemon essential oil and asked that she do some sponge baths to help open his pores and to help cool his body.

We had also asked the bonesetter to come and see what he would say and he had a completely different approach. He felt the baby’s skull bones and he diagnosed his skull bones of being stuck from hard labour and he did something that we would consider a craniosacral adjustment of the skull and then he said the baby needed a paste of castor oil and ground nutmeg applied to the central fontanella, which is what we did. Marie-Lucie brought him back the next day and he was well on his way to recovery. I like to give that story because it is a wonderful example when it comes to situations of extreme healing, how we use the modalities and co-treat with our Western way and the Haitian way.

V: What is it like to see so many patients in a day? In the context that most herbalists are familiar with and work in we have this idea that when you see someone you need 2 hours, that there must be detailed case taking and analysis, and so on. What is it like when you don’t have nearly close to that amount of time and may not even be able to communicate with your patients through language?

J: First of all I want to put this into context. We figured out very fast that anybody who was too intellectual couldn’t function in such an environment as a healer. If you ask yourself too many questions you won’t be able to function there and you have to make a lot of tough decisions before you even begin. Such as: there are things you are not going to treat, we didn’t do shortsightedness, diabetes, caries, and advanced chronic disease – which is not so prevalent in the first place because the population we were working with, the poor people in the ghettos, is what I like to consider a virgin population by and large. They had never had pharmaceutical drugs, vaccinations, operations, or anything else – they were just people who had never been medically treated, and they respond marvelously. They have what I would just call for now more superficial acute diseases and they respond very, very well. We are here to do emergency medicine. That was our focus going in; it was simply not possible for us to focus on treating chronic diseases.

That’s already the shift you have to decide on when you go into a disaster situation, to say we are doing emergency medicine. Since then the clinic has evolved because we have been there for a long time now and we do work on things such as very big difficulties in pregnancy, handicapped children, diabetes, breast cancer and other things like that. But at that time we were doing emergency medicine exclusively. We individualize, but you can’t individualize too much. There is something that I knew from Chinese medicine, which is the art of getting to the point in 3 questions. I told everybody you have to perfect that. You have to very quickly have the three questions that eliminate everything down to 2 or 3 remedies – then differentiate between them and you’re there so that you can on average treat a person in 5 to 10 minutes. I had to see 150 people a day, I was so exhausted that I couldn’t function anymore and we had not by any estimation seen everyone in line. The line looked to be the same length at 7AM as it did late in the afternoon when we finished, because we couldn’t go on. The other thing is the environmental context, with this brutal, damp, tropical heat and you’re being eaten by mosquitos top to bottom the entire time you’re sitting there. So for Jinpa and me, what we did was we just allowed ourselves to be in some kind of a trance or autopilot state using intuition. This is not the kind of intuition where I’m intuiting something that I have never heard about or have no experience with. I’m talking about intuition that comes out of a lot of knowledge and experience. For me, it was actually a really nice experience to be in a situation where I can’t intellectually think; I don’t have the time, everyone around me is screaming, I’m scratching so much I’m close to fainting, we were very hungry, we couldn’t eat, it was very dirty, it was extremely unsafe to eat, we couldn’t eat until the whole work day was over, there was no water… It was beautiful to see that when you have to, you can operate like that as a healer; I believe you have to be trained though. I don’t know if that could work if you had no prior knowledge of working in such an environment.

(Robinson takes Marie Lucie to treat a person struggling to breathe)

(Robinson takes Marie Lucie to treat a person struggling to breathe)

V: What can you tell us about the COVID situation in Haiti? You mentioned in the last newsletter that it doesn’t seem to be affecting the population very much at all. (As of May 27th, 2021)

J: COVID has done very little in Haiti up to now; they’ve started a large clinical trial to find out why that is the case. There are a lot of ideas that have not been verified, such as that there are very few enclosed spaces – the vast majority of the population essentially lives outdoors, the houses don’t have glass enclosing the windows and the doors are always open and wind is always blowing through the houses. Also, it has been discussed that half of the population is younger than 18, as well as other factors relating to Haiti being an underdeveloped country. From my own point of view, it is very well worth considering that they are so unspoiled by civilization in many ways, that the population tends not to suffer from deep chronic diseases. The kind of conditions that we are always pointing to as making a person vulnerable to COVID, don’t exist for the vast majority of people living in Haiti. This is a sugar producing country, even the poor kids do eat sugar, but they are so hungry so often in between that they do not have diabetes. No chance.

In the pre-COVID era, it was established basic epidemiology that you do not start to vaccinate while an epidemic is ongoing, because you’re essentially going to create mutation pressure on the virus. In this case, it is remarkable and frightening to me that now that vaccination has started in Haiti, although most people don’t want to get vaccinated as they are very suspicious against vaccinations, that now suddenly COVID is becoming a problem. There are rumors that now that the Brazilian variant has arrived it mostly hits the gut, so people get diarrhea like symptoms for 2 or 3 days and then are dead. I think it’s way too early to say much about it, so we are also right now quickly looking at how to adapt our protocol. Up to now we’ve had really amazing results [treating symptoms] just using essential oils of peppermint and eucalyptus, which are antiviral, antifebrile and bronchodilating, so I think peppermint is still a good idea for a virus affecting the gut, but we may have to rethink things. I’m just waiting to get past the rumor stage, so we can differentiate between what we are hearing about the symptom picture and what is actually going on. We need to get things substantiated, because the political situation is completely corrupt and malfunctioning at this point. People are not even sure that what is now being said about COVID in Haiti is not just a series of rumors that the government has put out in order to manipulate people in some way – the political situation has deteriorated to such an extent.

The rumor that suddenly there are COVID cases and people are dying from it, makes people not sure that this is not a way of scaring them into vaccination and whatnot… It is very hard to verify a lot of things in Haiti because there is no free press, there is no functioning government, it is a complete mess.

V: There seems to be a climate of distrust and suspicion that moves in many different directions.

J: Yes, and it is well justified and well founded distrust.

V: What can you tell us about traditional Haitian herbalism, and some traditional herbs that are commonly used?

J: Traditional Haitian herbalism is largely rooted in African herbal traditions. You find a lot of similar ways of thinking, similar medical understanding, as you would find in Africa. So for instance there’s the bonesetting aspect, which is very strong in African traditional healing systems, and it is practiced in a similar way with the patient just lying on a mat on the floor and the healer will use his or her feet to push the bones into place. Diagnosis very much has to do with looking at the state of the blood. There’s a strong emphasis on the evaluation of the state of the blood, and there’s some overlap with other traditional systems in this respect. They will think in terms of: is the blood good or bad, does the blood rise, is the blood curdling – when it is bad, the blood has a tendency to curdle. Is the blood curdling because of things the person ate and ingested or because the emotions are going overboard? You have this situation with a lot of heat and sweat and really explosive emotions. Many Haitians are very volatile emotionally and can get unbelievably angry, and in the those moments there is, for lack of a different word, a phenomena where the blood curdles and you can literally see it where there are stains under the light part of the skins on the palms of the hands. We might want to intellectualize and say there’s microscopic bleeding and thrombosis. That’s a big warning sign and they need to rush the patient to a clinic to have them treated immediately, otherwise they can die. We’ve needed to deal with that at the clinic also.

Our bonesetter and Jinpa grew up in the culture and gave us crash courses on this, because you would get patients who sit in front of you and they would say things like, ‘I have bad blood.’ Even when they say ‘I have anemia’ it means something different than what we understand by the word. We mean not enough red blood cells, whereas they basically mean not enough of whatever good thing there could be in the blood as a consequence of malnutrition. They may have enough red blood cells, but it really means I don’t have sufficient blood sugar, fats, proteins, and all the rest of what is essential to me – I’ve been hungry for a long time. It was very necessary for us to also understand the bases of Haitian herbal medicine to have a proper interface with the people who came to us speaking from that place of understanding.

V: Are there any particular herbs that you’d like to discuss which are widely used traditionally?

J: Haitian herbalism [and] Haitian culture is of course a mix which draws from the original native [Indigenous] people who lived on the island, then the African slaves who came from many different tribes and what would now be the modern countries of Africa, and the cultures of the Spanish and French conquistadores. It is very much a cultural melting pot, which is also reflected in the use of the most common herbs or medicinal plants in Haitian herbalism today. Many of them are plants that came with the conquistadores, or that were otherwise brought in; such as cacao (which would have been local), orange leaf, lemon, the citruses, peppermint, basil, cinnamon leaf – I even saw loosestrife – and chamomile flowers which are available in the stores. None of that we would expect when we ask the question about commonly used herbs in the Haitian tradition. I was frankly also surprised. There is, if you wish, a full integration of European style herbalism in popular culture and of course they also use the fruits and veggies that are around such as garlic, papaya, and things like that. Papaya for instance, because it is rich in digestive enzymes, is used as a poultice on wounds. The men also use papaya seeds – and this is really more traditional – because they have a jelly like cover; the papaya seeds, they look like sperm, and based on the doctrine of signatures/language of plants, the men eat the seeds in order to increase manliness. You also have Jamaican dogwood and you will find guys by the roadside with huge glass containers full of Jamaican dogwood soaked in local cheap rum. You can go to them to get your shot glass full for your virility, and things like that. Other examples that would really be more local is for instance the use of boiled guava leaf, which is astringing. The taste frankly reminds me a little bit of blackberry leaf tea, so they use it for diarrhea and also to astringe the guts. They have a kind of a plant which is a creeper with fleshy heart shaped leaves, a kind of liana – they call it in French, liane molle. The leaves are soft and can be cooked to a kind of spinach like consistency, and this is used as a blood builder, for anemia, but also as a demulcent.

Most notably for me is the use of nutmeg. We discussed the use of nutmeg in the clinic in our last newsletter, and I want to encourage people to sign up for the newsletter because we always include case histories and new aspects about healing plants. I try to make it an educational newsletter for people who are plant healers. Ground nutmeg is used very much in Haiti for paralysis type symptoms related to strokes. What is very interesting is that, as nutmeg is a strong remedy, those very types of symptoms will develop in someone if they overdose on it. We find ourselves back at the alchemical truth that a poison can, in a tiny amount, heal what it can produce as a symptom. That principal is the basis of homeopathy, of course [the homeopathic law of similars: Similia similibus curantur, “likes are cured by likes”]. Nutmeg under the Latin name Nux moschata is a homeopathic remedy that will cure all those very same symptoms so I thought it was very cool as a homeopath to see that the local herbalists use nutmeg powder, a pinch under the tongue, in exactly the same way we would use Nux moschata in the potentized fashion.

(The Herb Garden Enclosure)

V: Is there anything else you’d like to address? Are there ways that people can help through donations in any other way?

J: Our clinic has really only survived because people have always taken a real interest in our work and donated basically all of the medicines. All of the herbs, dried herbs, tinctures, homeopathics, essential oils – it’s all donated and people can send us an email through the website if they have a question about what we would like to be sent in terms of clinic supplies and where to send it. We ship things mostly from New York, but sometimes also from Europe. That is a huge help because none of us are paid. We are all volunteers. We collect cash to pay for the costs of shipping and everything goes straight to Haiti. We are trying to be the slimmest organization possible, one where no cent is lost. We do pay the people on the Haitian side because they have no other means of income – unemployment is probably between 80% and 90% in Haiti and we pay them $40USD a week, we don’t even know how they can survive on so little, so do not think that they can go out and buy themselves a mansion, they cannot. In fact, Marie-Lucie, now that we can’t run the clinic out of the usual location because of the COVID curfew, is running it out of her home which is kind of a shack. Just a couple of concrete blocks put together with a little bit of corrugated tin on top. Any donation of cash, or natural remedies is very, very welcome. Use your connections, see if you know somebody who owns a health food store, a distiller, other such companies. We take things that have been expired, sometimes we rebottle them or we take things that have reached their sell by date. Just contact us if you have a question and we would be so thrilled. This is truly the herbalist’s and aromatherapist’s clinic, it has been fueled really by their efforts and donations.

1 Readers interested in further exploring the science of homeopathy can refer to the award winning homeopathic medical research undertaken by Professor George Vithoulkas [here]

If you would like to check out more information about the Clinic or learn more about how you can help, please visit www.haitinaturalclinic.org

Herbal Education and the Medicine of Experience

Reflections on Herb Camp and the Meaning of Being “With It.”

After a long period of social isolation, we were finally able gather under the banner of ‘Herb Camp’ – the first event of its kind in Ontario, a herbal gathering with a strong focus on teaching clinical skills to budding herbalists and herbal enthusiasts from many different walks of life. Students who were at different stages in their herbal education attended the event, and there was a strong feeling of conviviality amongst the group along with a real eagerness and willingness to share and to learn.

One of the things that Herb Camp really illuminated and affirmed for many of us was just how universally applicable and relevant herbal medicine is – it can be approached from wherever you are in your life, and applied in a variety of different ways, contexts, and circumstances. Some of the students were keen on learning basic skills and tips to practice herbal self and family care, while others were on the path to becoming clinicians, focused on learning how to treat serious pathology through the use of plant medicines. And it is not despite, but because of these differences in orientation, that Herb Camp was marked by a mutual enhancement of experience and insight. The teachings that are received from the plant world are simultaneously personal and universal in their scope and range of applicability. Arguably the most important quality of an herbal student and teacher alike is the ability to embrace the dimensions of experience that the plant world opens up for you, being willing to learn to follow the plants where they want to take you. Herbal medicine is a medicine of relationship and experience – of the profoundly personal and the timelessly universal.

Like all of the true healing arts and sciences, there is an element of transmission that must take place when it comes to herbal education. There is clearly an essential place for facts, for textbooks, for lists and data, for lab reports and clinical trials in the training and upbringing of an herbalist. But there is an element of direct, personal experience that must also be present if an herbalist is to really come into their own. This can only happen in the flesh, tête-à-tête. The experience of working directly with the plants cannot be underestimated. An herbalist must, of course, learn to deeply see the plants that they use, to experience their medicine (the plants are more than dried material that shows up on your doorstep in plastic bags!). When you get to know an herb in person, that herb transmits some of its medicine to you, medicine that you can then carry within yourself as a gift and as a responsibility. The shift may be subtle at first, but in time, if that gift is properly nurtured, there is no going back. Before your know it, you realize that your perception of the world has been indelibly marked by all that the plants have given of themselves. It then becomes incumbent upon you to learn how to give back. With every act of transmission there comes a new facet or dimension of knowing and of sharing.

There is also the importance of direct and immediate participation when it comes to herbal education. This means in person, direct contact with a teacher and with fellow students. The same can be said of learning in general, as the great philosopher of education and social critic Ivan Illich once pointed out:

“Most learning is not the result of instruction. It is rather the result of unhampered participation in a meaningful setting. Most people learn best by being “with it,” yet school makes them identify their personal, cognitive growth with elaborate planning and manipulation.”

Our most lasting and significant memories of learning (and of teaching) are always tied to particular people and to specific places. Learning is embodied activity, and not a purely mechanical or cognitive exercise. After not having had any opportunities to gather in person for over a year, this fact really did hit home for the attendees at Herb Camp, teachers and students alike. It is shared participation and exchange in a meaningful setting that allows for deep-seated growth and development to take place. And when it comes to training in herbal medicine, this being “with it”, as Illich calls it, cannot be left out of the equation. We are, as herbalists, working with people after all, and we cannot learn to work with people who come to us in need if we do not learn how to be with others in the fullest and deepest sense of that word.

There is something truly therapeutic about being with others, as every therapist and medical practitioner, irrespective of their training or orientation, will tell you. Healing is a process that often takes place in the depths of the self, but the self is always already being with. Part of the significance of multi-day educational gatherings is that they allow us the time and space to step outside of our habitual routines and to really be with others, to talk and share jokes and meals as well as to explore involved and complex insights and ideas. Intimacy and conviviality is a crucial part of what differentiates a true learning environment from an impersonal place of instruction. When we allow ourselves to be with others in this way, we are engaging in an act of self-care. Education should be healing, for in learning we are given the opportunity to tend to ourselves, and to come back to ourselves anew. And as Illich reminds us, if we do not learn how to take care of ourselves, and cherish the opportunity to do so, then we cannot hope to be effective when it comes to taking care of others:

“Effective health care depends on self-care; this fact is currently heralded as if it were a discovery.”

Herbal medicine has known this all along. Herbal medicine is intimate. It is as much about the path that took you to the place where you are today as it is about the here and now. It is about the care of the self as much as it is about the care of others, and of the earth itself. Herbal medicine is not concerned with the production of medicine as a commodity, but with the propagation of medicine as relationship and experience. There is no better way to learn this medicine than being with others.

Honouring our Teachers

Honouring our Teachers: Experiencing Reality and the Art of Learning to See the World.

Judgment has its place in the arena of practical life. Without judgment, it would be near impossible to navigate many of the fine details of the world of average, everyday experience. Judgment comes from the head. There is a quickness to the world when we perceive and relate to it through our heads. Being oriented from the head may allow for a certain efficiency and expediency in the practicalities of daily life, but it can also lead us to rush and ignore nuances, complexities, and the implications of the unseen relationships and subtle dynamics that underlie the given.

A great deal of conventional education is oriented around the head. This leads to an abstract view of the world, which in the extreme gives one the impression that the world can best be understood through calculation. This, again, is a world that is oriented around following a designated set of rules and orders. Consensus reality, for short.

Where our head rushes, the rest of our body goes slowly. The body has its own natural rhythms and cycles that can’t so easily be coerced into rushing or speeding up. Nor would it be in the least advantageous to do so. The body operates on its own time, whereas the head can be influenced, directed, or even manipulated by the dictates, pressures and demands of consensus reality.

One of the primary causes of illness can be said to be a lack of integration between the head and the rest of the organism (the whole being made up of body, soul and spirit). When the head grasps things too quickly, or in an incomplete manner, the rest of our organism has a difficult time assimilating and absorbing what the head has become convinced of. When we only perceive the world and come to knowledge through our heads, this can create a state of disconnection that can lead to deep-seated feelings of dis-ease, sending waves of dissonance through the organism, eventually resulting in physical pathology. In so far as our teachers allow us to recognize this, helping us to balance and assimilate the head with the rest of our being, they can be said to be great healers.

When our organism is not able to assimilate what the head has been presented with, then there is no chance of that information engendering joyfulness. Our greatest teachers can also be said to be caretakers of the life of the soul, helping us to recognize and understand our feelings, and thereby laying the foundations for the adoption and embrace of empathy and compassion in our daily lives. This is why teachers have great ethical and moral responsibility.

Teaching in the true sense is an act of transmission. Transmission is what makes teaching an art: the teacher shares with their students what they have been able to experience and assimilate in their own lives, shares with their students all that they themselves have been shown by their teachers. This act of transmission can be traced back in an endless and unbroken succession of teachers, stretching all the way to the very beginnings of human culture. Teaching is an intergenerational activity that draws on the infinite repository of human wisdom, our living human heritage, and allows this to be received and developed by the younger generation in a good way. If there is a connection between teacher and student, a bond of sympathy is formed which allows the student to borrow and eventually integrate as their own the tools for navigating reality and shaping and refining experience that the teacher has been graced with.

Thinking in the true sense can only happen from out of the whole organism. Thinking from the head alone can often lead to dissociation, to feeling cut off and separated from the world. The words ‘thinking’ and ‘thanking’ are etymologically related. To think means to give thanks for what one has been given to see. The teacher is the one who is tasked with facilitating this ability of the student to learn to truly see. The teacher guides the student so that they can learn to teach themselves, and in time teach others as they have been taught (but always and forever in a new way, for each student and each teacher have a uniqueness that is only and truly their own). A significant part of the art of teaching consists in allowing the student to learn to see the world with reverence, humility, and even awe. Without our teachers we would be nowhere, for it is they who show us how and in what ways we are connected with the world. It is they who facilitate the development of our experience of reality.

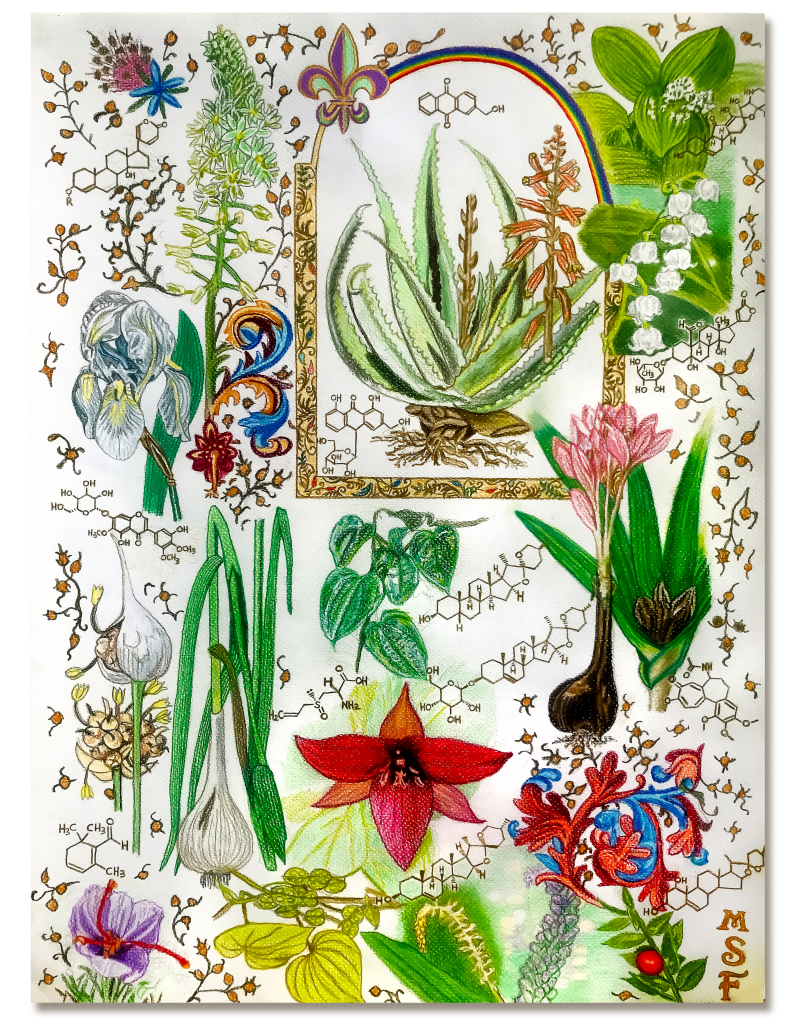

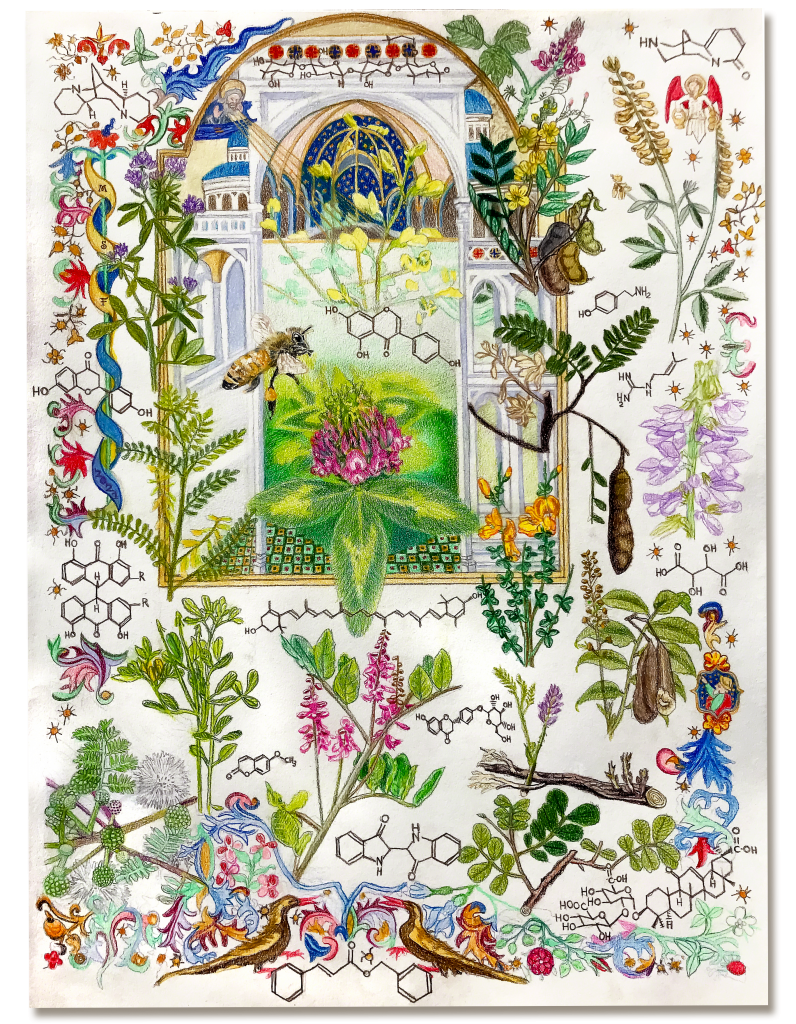

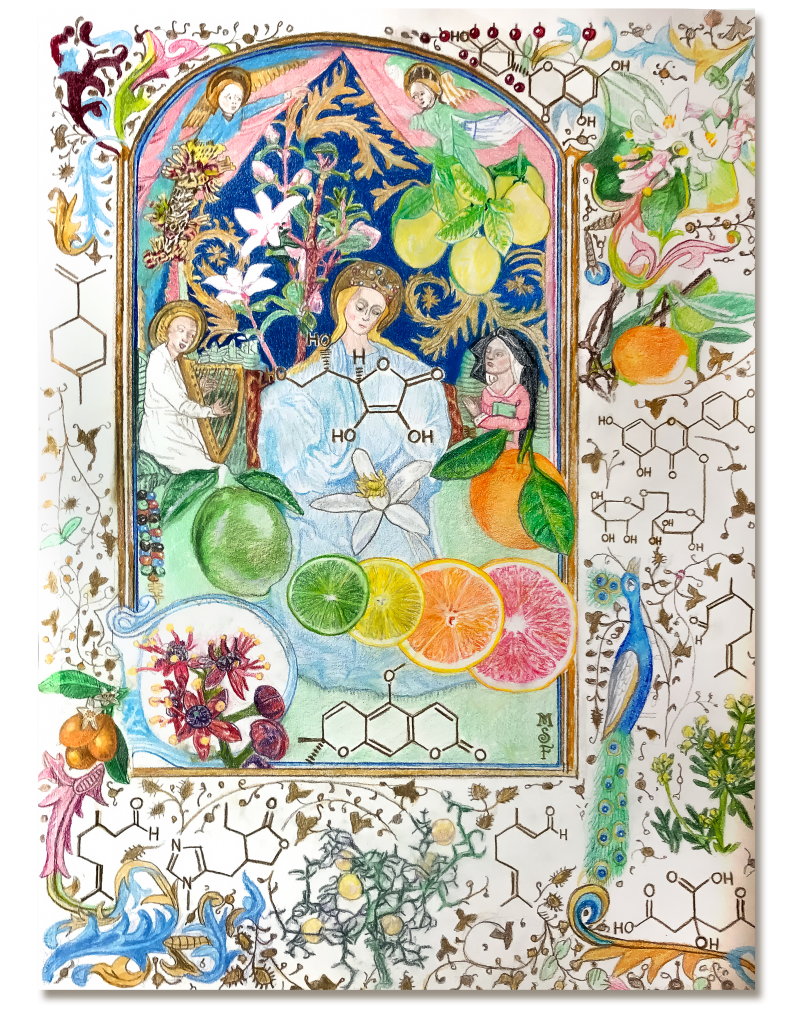

Illuminated Phytochemistry: An Interview with Michael Steven Ford

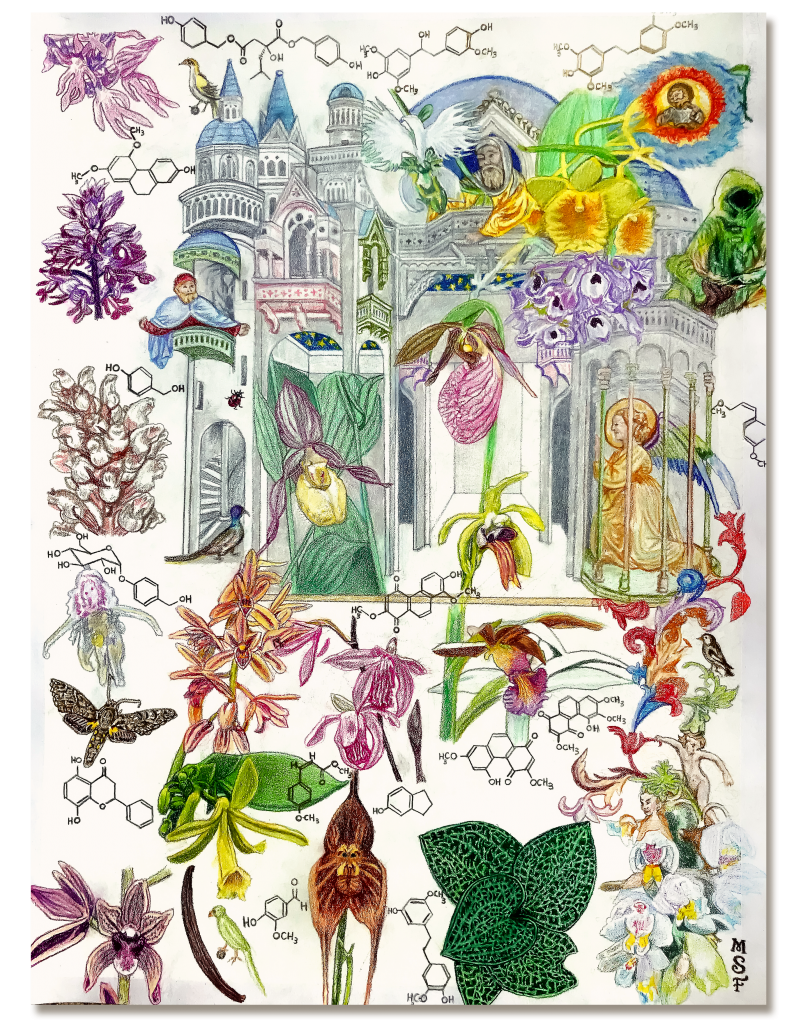

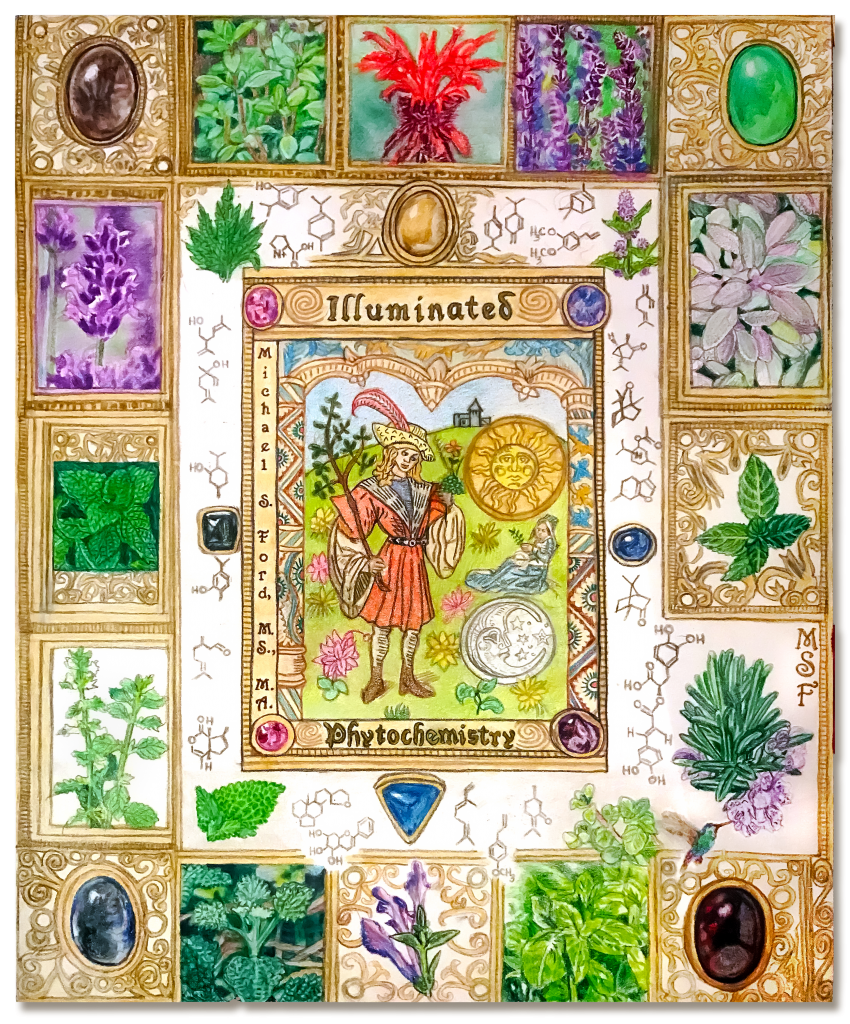

Welcome to an interview with Michael Steven Ford! This interview was conducted by Victor Cirone with illustrations created by Michael.

Victor: Tell us a little bit about yourself!

Michael: I’ve been involved in the herbal community and have been working with herbal medicine for about 31 years now. It was 30 years ago that I took an apprentice program with Rosemary Gladstar in Vermont and then went on to start my own herb company – Apollo Herbs – manufacturing various herbal products and providing wholesale services to health food stores in the New England area. Then I went back to school and started studying the science of herbalism and earned degrees in botany and in pharmacognosy, which is a graduate program in pharmacy school that deals with natural product chemistry. I was there from 1998 – 2004 in the graduate program, and then I began teaching. I had been teaching herbalist apprentice programs throughout college, but in the end I ran about a dozen or more herbalist apprentice programs in the Rhode Island area, which is where I’m from originally. I later moved out to California and began taking all of the research that I did in graduate school and turning it into a book. In the book, I go through the plant families one by one, exploring various plants that have healing or nutritional or pharmaceutical value, explaining the trends in their chemistry. I’m also illustrating these plants and the molecular structures.

What can you tell us about the illustrations? They are quite striking and unique. There are not many herbalists that are creating work of this kind.

M: I forgot to mention, before I met Rosemary and studied herbalism I had been studying illustration at Rhode Island School of Design. I was going to school for illustration in the beginning, and then my whole course of study changed. Now I’ve come back and I’m tying it all together. I’m taking all of the botany and the pharmacognosy and the phytochemistry and trying to bring it to life in a way that honors the spiritual side of healing and of nature. I’ve chosen to do it in the style reminiscent of medieval illuminated manuscripts, of which there are many. These illuminated manuscripts tell stories, usually of a saint, or explore other religious motifs. I’ve been removing all of the characters and instead putting in all of the herbs, and then complementing the background with the molecules from their phytochemistry. At times, I’ve been putting in fairy spirits or different magical kind of images, but again in order to evoke the feeling of the spirit and essence of the plants. What I’m trying to do is to tie modern chemistry and science into that by implying that the spirits of the plants, or the essence of these plants, imparts its healing and nutrition and value to us through its chemistry. This is, of course, true, even if we are working in a holistic manner; it’s nice to know why certain things work, how they work, how to quantify the strength of something. The science does have a value, although I think that in modern society it has been greatly exploited.

There’s definitely a strong, almost alchemical resonance and quality to your illustrations. Can you say a little bit more about the traditions that you have been inspired by? Is there anything else that you can share about the tradition of the illuminated manuscript for those who are unfamiliar with such work?

M: I don’t know that my journey has been very traditional, it just kind of happened because of my various hobbies and interests and educational pursuits. I had learned the material and then when I was in the graduate program I had to put together a large study guide to learn all of the plants of the various families and their chemistry for my exams. I turned that research into a book later, which I never would have done otherwise. The idea of illustrating it relates to the fact that enough people are intimidated by the chemistry and the science so I wanted to make it seem more inviting and more fun, and show that there is an alchemical component to working with plants, nature, and medicine. The pharmacognosy that I have been studying is where modern-day pharmacy derived from, a lot if it anyways.

The traditions that used these plants often involved shamanism of some sort. I went to Peru in 2002 and studied with some Peruvian natives who were teaching shamanism to Americans. We did a couple of years of study. We needed to study with them before they let us go down and meet their teachers because they wanted to condition us to their culture – or uncondition us from our own culture, rather. When I was there, one of the old medicine men told me that he thought it was important that I honor my ancestors. I was into that, but I had never done it. When I came home I started researching my genealogy and trying to find out whom my ancestors were. Ultimately, that led me to writing a whole book about it, and I started illustrating the ancestors. I had inherited a lot of old photos, and so I began creating illuminations around my ancestors. I drew pictures that looked like medieval illuminations, but I put all the pictures of my ancestors in, creating something to honour each of the lineages that I had. Later, that gave me the idea to remove the images of the people – instead of it being my family, let’s make it a plant family. I started doing each one of the illustrations about one plant family, though in some cases I’ve done an order, because some plant families only have a couple of medicinal plants and I’ve been doing 15 plants in each one of these pieces. I’ve been working on them for a little more than a year now, and I’ve done 13 of them so far.

I’ve been doing this during the pandemic as a way to keep myself focused, it’s been a great refresher for me, too, because I’ve had to go back and look at all of the botany again and make sure that I’m drawing it anatomically correct, and looking at the chemical structures and making sure that I didn’t make any mistakes drawing them into the designs. I know that not everybody wants to learn this material, but if you are interested, learning visually is a good way to do it, especially when you start to associate chemical compounds with the plants that they are naturally found in. There’s not a lot of language associated with what I’m doing – it’s mostly symbolism and visual learning. The symbolism of chemistry and its molecules is universal in the world, even though there are some letters in there like ‘O’ for oxygen and ‘N’ for nitrogen. The rest of it is all imagery. Maybe some day there will be a need to preserve the visual component of which plants are in which families containing which compounds – I think that is kind of what I’m doing. Not that this information isn’t out there. I’m just putting it together in a new format because I have the ability to do it, I’ve spent a lot of time learning this knowledge, and now by putting it into a book, I can help other people to learn it, too.

You’ve mentioned that many people encounter difficulties when trying to study and deeply understand phytochemistry and its relevance to herbal practice. Perhaps you can say something about why you feel phytochemistry is important to the contemporary practitioner?

M: I think it’s a great tool; the chemistry is a very valuable tool for us to better understand and work with the plants. Especially when it comes to the solubility of what you are trying to extract from an herb. If you understand the basics of what type of compound, and how it would be classified, and what the basic actions are, and then looking at the basic polarity and solubility, you would know whether you could extract it with alcohol, oil, water, or glycerin – we’re not allowed to use other solvents, in pharmacognosy we had to use a lot of other things that I would rather not have used! It really helps to know if something requires Everclear to extract it because it has a lot of various fatty acid compounds or cholesterol or other very lipophilic compounds that extract well with organic solvents. And then there’s the sugars – if you’re making an immune formula that has a lot of polysaccharides that are complex sugars that stimulate the immune system, then hot water is sometimes sufficient depending on what plants you are using, and what you are trying to extract. Oftentimes there is a mixture within the plant, and that’s the reason that 50% water and 50% alcohol seems to work well – not that it’s a magic ratio or anything, but that 1:1 ratio does work for a lot of herbal extracts, because its right in the middle. Likewise, I am also very interested in essential oils and hydrosols. I got involved with cosmetic formulation and manufacturing for a while. It’s the same thing, just using it for a different purpose – in terms of getting plant extracts and manufacturing products with them – which led me to teaching more about it.

What can you tell us about the book? Does it have a title yet?

M: I’m planning on calling it ‘Illuminated Phytochemistry.’ I’ve created a cover for the book – the cover has the mint family on it and I put some of the menthanes and various terpenes that are in that family on here. That was one of the very first ones that I drew. Like I said, I’m on the 12th or 13th illustration. I’m working on the Mallow family right now. I’ve done the Orchid family, the Apiaceae, Rosaceae, Fabaceae, Asteraceae and Solanaceae [Nightshade] family, to name a few, but I mean there’s hundreds of families, so its unrealistic to think that I can illustrate them all in a reasonable amount of time, which is why I’m just choosing the ones that are of healing, medicinal, nutritional, and/or cosmetic interest. I think it is valuable to organize this information in this way so that you can quickly look at a plant family and see which plants are closely related, and how they are related chemically, so if you didn’t have one plant available, you might be able to substitute it with another plant, or you could see which plants you could extract together because they might have similar solubility or action. This is far from folk herbalism, what I’m doing, since I’ve organized it using the scientific tradition. But I’m really hoping to blend the two. With the art, to use the right side of the brain to teach more left-brain material. I can be very left-brained, but I can be very right-brained, too. It just depends on what I’m focused on at the moment. I think that we can all do that; we just have to believe in ourselves to do it.

We are all conditioned in certain ways and have tendencies towards certain kinds of activities, but the potential for both right – and left – brained activity is always already there, it just depends on the circumstances we find ourselves in and how our minds get awakened.

M: Finding the right teacher can be really important, because sometimes somebody presents this sort of material in a way that is really inspiring to others, as well as in a clear way. You also have to be willing to do the work. When you are getting involved on this level, there is a certain amount of discipline that just comes with the territory, as in running a lab or approaching taxonomy or phytochemistry – these are disciplines that you have to study before you’re allowed to do certain work, there are prerequisites involved. I’ve taken a lot of this material out into the public to teach people who don’t have those prerequisites. In some cases it can be intimidating, but other times it really makes people say ‘wow, that’s cool’ and ‘I wish I knew more’ or ‘I want to learn more’, and those are the people I’ve worked with over the years.

What about the text that is going to accompany the illustrations?

M: The coloured illuminations that I’m doing, I don’t have the publisher yet, so I can’t say if they will all be in the center of the book or will appear as chapter heads for each section. I will probably go from simple to more advanced, starting with the monocots and going to the dicots and ending with the aster family, which is the way that most of the botanical texts go. I might put the illuminated image at the front of the chapter for each corresponding plant family, and then have the text, and then have smaller illustrations of e.g. the shape of a leaf or other types of botanical illustrations that will help people learn the plants. It’s not just about phytochemistry – its bridging botany and phytochemistry together for the purpose of healing arts.

We are trying to compile a contemporary history of herbal medicine at Everything Herbal, and we are asking various people to share their experiences with the evolution of the herbal medicine world as they’ve experienced it.

M: It’s changed a lot since I got involved. I’ve been involved for the last 30 years – big business got involved over that time period. When I first started my herbal company in 1991 there weren’t the regulations in place that there are today. The ‘good manufacturing practices’ are more stringent now than what companies were doing back at that time. Much of it has to do with sterility, cleanliness, proper identification, record keeping, making sure you have good procedures for extracting and preparing your products. They want the products to be good quality, and there are good reasons for those things to be in place. We are now dealing with a corporate, multi-billion dollar global industry. I’m concerned about the plant populations and I’m hoping that they aren’t going to be exploited too much, where we start losing various species of plants due to overharvesting or environmental damage. I saw that – I was one of the earlier members of the United Plant Savers because I was studying with Rosemary Gladstar when they formed that group; they were meeting up at Sage Mountain when I was still a student. There are a lot more organizations today dedicated to conservation, more educational opportunities, and the preservation of the knowledge – including support for indigenous knowledge and indigenous cultures. There is more respect for diversity in general. Lately I’ve seen politics becoming involved too, and people getting upset. I’ve just tried to stay out of that to the best of my ability although I really hope that we can all learn to just get along and respect each other. That’s what the whole human race needs. That’s such an understatement!

Herbal medicine has also been so viciously attacked by the allopathic establishment…

M: I remember when I was pharmacy school everyone was very skeptical of me there at first. The allopathic environment was not pro-holistic. I gave a graduate seminar on the use of hallucinogenic compounds from plants for psychological and psychiatric research and they nearly laughed me out of the room. Now it’s a hot research topic. But 20 years ago, they just weren’t ready for it. All that research started in the 60s, it’s not anything new, but they were just closed-minded to it. This has to do with international patenting laws, what is deemed a drug and what is not, and all the regulations around all of that. I like to point out that the word ‘drug’ comes from the old Dutch word drogge which means ‘dried plant’.

What are some of the directions that you’d like to see herbal medicine move into?

M: I think it has moved a lot, I don’t know that I’m the right person to say what it should be for other people, but I would like to see it more accepted by science as something valid. I’d like to see the scientists have a more diverse approach, where they can incorporate nutrition, herbs, as well as allopathic medicine and various types of physical treatments into their practices. I think we are moving in that direction. I don’t think the insurance companies are ready to jump behind it, and go along with it as part of standard practice, though. I guess it depends on where you are and who you are working with. I’m surprised to see, still, the amount of resistance that is out there from some people. But it’s not my place to judge. They have a lot better marketing programs – the pharmaceutical companies.

Maybe you’d like to talk about your interest in psychoactive plants. It is a topic that can be quite polarizing – you have some herbalists that are strongly opposed to the use of psychoactive and entheogenic plants and other herbalists that totally embrace and are very excited by the potentials behind such usage.

M: I can clearly see that there’s a polarity there. I don’t see any reason why these plants can’t be used, at least experimentally as medicines, when we have allopathic medicines that have all sorts of bad side-effects and that people are supposed to stay on for long periods of time. Some of the shamanic techniques that are being tapped into are helping to release trauma through using these types of compounds. There was often some kind of ceremony or ritual, someone observing a person to ensure their safety, and done in a context of working under somebody who was experienced and knowledgeable. We’re not talking about someone who wings it, because then they are risking the possibility of things going wrong. I don’t want to say one way or the other – I don’t have a problem with people using these plants traditionally, but I don’t want to sound like an advocate either.

It depends on the individual and their need for therapy. I understand that it goes beyond that – there’s a whole culture of people who have used these things for other purposes, going back to the hippies and the 60’s and the Grateful Dead & psychedelic rock… I’m not even old enough to have been around for that, though I appreciate the music. People are going to use various substances whether they are allowed to or not. It is better to be safe about it, and perhaps if there was more education available… I don’t want to sound too idealistic in my thinking. I think it’s a shame that there’s so much drug abuse in our culture. We should be looking at why people are engaging in this kind of behaviour. Instead of blaming the drugs, let’s look at the definite social and cultural issues that are lying at the root of this behaviour. Let’s learn to use the compounds and plants more intelligently. I hope that someday we have a system that is more conducive to that, more accepting of that.

It’s interesting to observe the contemporary psychologists and psychiatrists who are using psychoactive plants and compounds in a therapeutic context. Some of them are doing interesting work, but it’s always within the confines of the psychiatric model. Definite limitations are set: we’ll allow you to experiment, but only if you are doing so within our officially sanctioned framework. Forget about traditional use, they’re not interested in traditional use. There is the traditional medical pharmaceutical model, which is open to very minor modifications, and that’s what you have to exist within if you are to be granted any kind of legitimacy.

M: The medical field tends to do that, to compartmentalize in that way. I’m not saying it’s the only way to approach it, but if you were going to investigate, there are maybe other ways, such as working with indigenous peoples and finding healers who are educated, and who can assist people with the use of these plants. There’s always a potential for someone to have a bad trip or to harvest the wrong plant or take too much of something and have a bad reaction, and you don’t want that to happen. This work certainly has the tendency to bring up people’s traumas, and if they have traumas and haven’t healed them, then there’s a chance that they might be triggered.

What do you feel herbal medicine has to do with understanding ecology and sustainability? Can you share some thoughts about the relation of herbal medicine to ecology generally?

M: I think that herbalism is one big part of our survival skills as a species and it’s probably the oldest, or one of the oldest, of such skills. And because of that it evolved a lot differently than lot of other systems that are operating now. A lot of the way things are operating now, in broader context, is based on corruption, a corruption of science, with the aim of trying to create global monopolies, which they have done. Humanity needs to live in balance with nature, it would certainly behoove us to, and herbal medicine is a huge part of that. It is very important that we preserve these traditions, that we continue learning and researching, and that we teach our children and grandchildren, and the future generations. That is a constant, that has always been the case, but even more so now because we have so many competitive fields that are against what it is that we are doing. It is all the more important for us to preserve what we have, updating it, and passing it forward. I hope that the future generations can use all of this as a key to living in harmony with nature and figuring out the various health problems of humans and animals. There is so much potential, it’s just a matter of getting enough of our collective attention focused on that potential. The people around the world are pretty united – a lot of people use plants, all over the world. That kind of a movement can be supported. It’s already there, but it’s an underground movement. I just don’t want to see it become further exploited into some kind of unappreciated resource that does even more harm to the planet.

Then it becomes a vicious cycle, the deeper the patterns and cycles of dissociation humans end up falling into the greater and more difficult are the perils we have to face in the long term. It’s one big self-defeating cycle. It can be said that the disease process often develops as a way of pointing out what the error is in our way of being in the world, disease as a means of making you as an individual aware of what you need to change or shift in your life. When you suppress that information either in an individual body or in the context of a larger ecological matrix, then you are simply creating an even more chronic, long-standing condition that is even more difficult to cure.

M: I agree. I would like to see the system less profit-oriented, too. I’m in no place to make that happen. It’s a shame that things have to be all about money when we are working with curing diseases.

Anything else you’d like to discuss or share?

M: I am going to be producing a website, I’m going to be selling botanical prints and some of the art I’ve been creating outside of publishing it outside of the book. There have been a lot of requests for posters, t-shirts. I have been posting the images on my Facebook page as I’ve been creating them, so I will likewise be posting more information regarding that.

If you would like to check out more of Michael’s work and follow the journey of his book, you can find him on Pintrest.

Healing The Rift

The Healing Professions, Human Freedom and The Social Good: Book Burning and the Psychic Depravity of Authoritarianism

From their heights the Gods reach down into the ocean of humanity and feel the warmth of love. We know that the Gods lack something when man does not live in love. The more human love there is on earth the more food for the Gods there is in heaven; the less love there is, the more the Gods hunger. - (Rudolf Steiner – GA 105 – Universe, Earth and Man: IX – Stuttgart, 13th August 1908)

Those who are genuinely engaged in the healing professions have an absolute and unshakeable responsibility to perpetuate and promote health, harmony, love, truth, and justice in the world. Medicine is to be practiced in the service of The Good. The primary task of a healing professional is to work for the benefit of humankind, to promote the flourishing of life, to alleviate suffering to whatever extent they possibly can, and to allow for individuals and communities to reach their highest potentials in body, mind, soul, and spirit. It is incumbent upon healers to cultivate the courage to heal in themselves and in their patients, for it is no small responsibility to help the sick and requires nothing less than unwavering and unfaltering devotion.

It is untoward for healers to perpetuate lies, illusions, and false-truths. Lies and illusions affect human beings in very deep ways, and are in fact the underlying cause of a great many illnesses and states of dis-ease. Our soul life becomes greatly compromised when we are fed unlawful images or repeatedly exposed to deceptive and manipulative words. Such impressions that are marked with the insignia of their own falsity and untruth create unconscious disharmonic resonance patterns that affect the entire organism in very adverse ways. Unlawful images direct the soul away from what is good, beautiful and true in nature, and this inevitably leads to states of malaise, characterized by mental instability and tendencies to violence. The healing of the soul and the healing of nature both require that we pay attention to the flow of inner images, and learn to be guided by true Imagination, which is integral to our capacity for genuine love and devotion.

True Imagination is also what allows us to feel into the inner experience of another, to demonstrate empathy. Rudolf Steiner taught that empathy is a prerequisite for true healing. Healing must start with empathy, for it is empathy that allows one to generate an understanding of and feeling for another person’s underlying circumstances and condition. It is empathy that teaches and allows us to metabolize another’s experience, and to recognize what it is that needs to be healed in them.

The Controversy

Recently, a massive controversy has erupted in the international online herbal medicine community. An article written by Stephen Harrod Buhner entitled ‘The Day The Woke Mob Came for the Herbalist’ is what sparked this controversy. This article is available here for anyone who cares to read it.

Many people took issue with Buhner’s article for a variety of different reasons, and many adamantly supported and promoted his views. It is not my prerogative here to explore what Buhner is or is not saying in this piece. Both sides of the divide have ended up accusing each other of misunderstandings, exaggerated and false opinions, distortions of reality, misconstruals of history, inflated egos, and all the rest of it. A condition of disharmony was created that is now reflecting negatively on the herbal community as a whole. We are dealing with a pathology that has infected the psychic life of our profession, and which has adversely affected the capacity of many to exhibit truth, empathy and understanding.

Irrespective of what Buhner said in his article, he had the absolute right to say it. If you disagree with his words, or the words of any other author, then there are a number of legitimate ways of voicing your opinion, and of raising critical opposition. It is through such civil debate and dialogue that we are able to strive towards the ideal of an enlightened society, as the philosopher Immanuel Kant understood it:

“Enlightenment is the human being’s emergence from his self-incurred immaturity. Immaturity is the inability to use one’s own understanding without the guidance of another” (Immanuel Kant, ‘What is Enlightenment?’).

Rigorous public dialogue and debate, with the aim of arriving at truth, is what allows for enlightened self-understanding to emerge in a social world. Censorship, and the negation of free speech, is inherently opposed to this ideal of communal truth making. When one speaks or acts in the public sphere they are accountable to all, for they are acting as a member of “the society of the citizens of the world” (ibid). We all must take full account of our words, for our capacity to speak freely carries with it immense responsibility.

The Freedom of Speech

One of the greatest negations of free speech and the perpetuation of authoritarian censorship is to be found in the act of burning books. This is how one herbalist of Toronto decided to respond to Stephen Buhner’s article. Book burnings have been carried out by some of the most despicable parties in world history, including the Nazis and the Hitler Youth, Mao Zedong (as part of his Cultural Revolution), and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (who in 1956 burnt the publications of Dr. Wilhelm Reich). Many other examples can be given to illustrate just how pernicious the act of book burning is, and how it serves as an assault against the pursuit of freedom, truth and justice. The motivations and values behind book burning are diametrically opposed to the motivations and values that a true healer should always and in all circumstances maintain and serve to uphold. Read more

Plants and Humankind

Plants and Us

Most of us show an appreciation, if not love, for the plants that surround us. But culturally, even if we recognize the nutritional, medicinal, and aesthetic benefits that plants offer to us, the complexity and deep rooted significance of our relationship with the plant world has been clouded over by the fast pace of technology and the demands of modern life. We are now at a time, however, when many are hearing the call of the green world anew, and for good reason.

Plants have always played an integral role in human culture. Besides providing us with food, plants have always served as our primary source of medicine. We can see that this is true even today in the context of modern pharmaceuticals: consider that of the most 150 commonly prescribed pharmaceutical drugs currently in use 74% derive from plants, 18% from fungi, 5% from bacteria, and 3% from vertebrae species, e.g. snakes and frogs. Plants have also served as a primary and essential source of inspiration behind the world’s great artistic, spiritual and religious practices and traditions.

It is without question that plants are essential to the foundation of life on planet Earth. When it comes to us humans, we simply could not have evolved physically, mentally, or culturally without the great services that plants provide to us. However, when we look at the relationship between human beings and plants closely, we see that it is one characterized by a process of co-evolution and cooperation that has gone on for millions of years. Animals, including human beings, have been shaped by plant life and have shaped it in turn. This process is one of reciprocity, and not one that is dictated and controlled by any of the players in the great web of life.

Modern plant biology has revealed to us that plants possess intelligence, engage in purposeful behaviours, transmit information, and even have a form of memory. When it comes to understanding the fundamentals of our shared life on Earth, it helps if we recognize that plants are not so different from animals after all. As plant scientist Anthony Trewavas has observed: “plants have the same biological criteria for survival as animals – the need to obtain food, to see off competitors, deal with pests and disease, and access mates.”(*1)

We are now in a time characterized by major global ecological challenges, and in order to face them responsibly and with integrity we must regain an understanding of our interdependence with the plant world. Much of the ecological hardship that we are seeing on Earth today has to do with neglecting our relationship to the plants, forgetting and losing sight of the intimacy that human beings have always shared with them. Valuing and protecting plant biodiversity will provide the resources with which we can forge a sustainable future. The plant world is the repository of vital information that will help us to deal with global challenges, from the growing threat of anti-biotic resistant bacteria to the dramatic environmental and climactic changes that are currently underway.

At Everything Herbal one of our primary commitments is to plants as medicine. From the perspective of traditional plant based healing traditions, a healthy organism is one that is in balance with itself and with the dynamic, vital forces that give it and define its life. Plant medicine is holistic medicine, and a holistic state of health means that all of the parts of an organism are working together to sustain a harmonious whole. Holistic health further means that the organism is in balance with the world that surrounds it and of which it is a part. Plant medicine has a great deal to teach us about ourselves, each other, and about the world in which we collectively exist. This has always been true, but it is perhaps especially true now, in these truly unprecedented times. Now is the time to learn to tap into the deep evolutionary memory of our embeddedness in the green world. This memory holds the keys to unlock the understanding of who we are as individuals and as a species, and can show us a great deal about what our place in the world can and should be. May the love that we share for the plants grow and prosper.

*1 Anthony Trewavas. Plant Behaviour and Intelligence. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014. Pg. 11.