An Interview with David Winston

This interview was conducted as part of Everything Herbal’s ‘Herbal Elders’ series. This series seeks to honour and explore the unique contributions of longstanding members of the herbal medicine community in Canada, as well as abroad.

This interview was originally conducted with Nick Faunus, Penelope Beaudrow and Victor Cirone, in July, 2022.

Reciprocity in herbal medicine

Everything Herbal: I’d like to begin our discussion by considering the place of reciprocity in herbal medicine. What can you tell us about this?

David Winston: Let me start off with a story and introduction. This year I’ll have been studying herbal medicine for 53 years. I started studying herbal medicine in 1969 and at the time all of my friends were interested in one herb, and I was interested in all of the others. Fascinating how today the interest in that one herb has grown tremendously, but I’m still primarily interested in all of the other ones. In 1969 there were no real herb schools, it was hard to learn about herbal medicine. People would say to me what do you do? I would say I’m an herbalist and people would look at me like I was an alien from another planet coming to abduct them. Why would you waste your time with something people did 100 years ago? I fell in love with plants and herbs, with being able to walk out in the woods and the fields and find medicinal and edible plants. My early learning came from a number of sources. Some of it came from books, I would read any book I could find on the topic, and at the time there weren’t that many. One of my first books was ‘Stalking the Wild Asparagus’ and then ‘Stalking the Healthful Herbs’ [both titles by Euell Gibbons] and ‘Back to Eden’ by Jethro Kloss. In reading these books, I was being handed knowledge of the generations, knowledge of our ancestors. And then I started looking for people that I could learn from. And it was difficult. I took a couple of classes from Dr. Christoper probably in the early to mid 70s. One of my friend’s fathers came to America from Germany and was really into organic gardening and farming, which he taught me. I had another friend in high school whose mother had studied Chinese cooking. I knew how to bake and we taught each other. This is one of the things that initially peaked my interest in Chinese herbs, learning to use them in a culinary way.

Reciprocity was built in – the fact that much of what I learned early on was not necessarily from a school where I was paying for the information. I remember one time we went to the World’s Fair in Montreal when I was a kid. My parents decided we were going to go for a little vacation up into Northern Quebec. It was a memorable trip. This was at a time when there was a fair amount of anti-English sentiment, which we didn’t know about until we arrived there. My mother did speak a little bit of high school French, but not Quebecois. Most of the time we would go into places and they wouldn’t talk to us. It wasn’t a question of whether they understood English or not, because as soon as they recognized we were English speakers they ignored us entirely, like we weren’t even there. We went into this one store, a general store, and they had horehound candies. I had never had horehound before, but I had read about it. So I had to get them. I put one in my mouth and within 10 seconds I spit it out, it was the most disgusting thing I had ever tasted in my life, or so I had thought at that moment. Interestingly enough, an hour later I wanted to try another, which I was able to keep in my mouth for 30 seconds. And by the end of the day I liked them. It was a gradual process of getting acclimated to the flavour. The guy at the counter noticed I bought these and was trying them, and he said to me in English, ‘are you interested in plants?’ I told him that yes, I was deeply fascinated. He started telling me about his favourite herb, a plant he called black snakeroot. I had no idea what it was he was talking about, he didn’t know any Latin binomials. He had a little bit of this herb, let me smell it and gave me some to taste. Many years later I realized that what he called black snakeroot I would call wild ginger, Asarum canadense. It was one of those experiences of recognition and generosity, facilitated by the plants. This happened even though I spoke English and he primarily spoke French. What made the breakthrough was plants.

I feel so fortunate to have been studying herbs for 53 years, and to have been in clinical practice for 45 years. I’ve got to spend almost my entire life in this community of people who love plants. For a very long time I thought I was the only herbalist in the entire Eastern US. It turns out I was wrong, but the majority of the other herbalists who I later found out about were often folk herbalists in rural communities, well known in their own communities but not beyond that. People like Evelyn Snook in central Pennsylvania, or Catfish Gray in Virginia, or Tommy Bass in Alabama. There were other herbalists too, they just weren’t particularly well known. I grew up in Maryland but we had moved to New Jersey, and there was a woman in Rahway, NJ, Henrietta Diers Rau, who I never got to meet but I found her wonderful but somewhat obscure book, ‘Nature’s Aid’ in the library. Henrietta trained at the British School of Phytotherapy in the UK, she was a practicing herbalist, not very far from where I lived. Some years later, in 1981, the first major US herb conference took place in Breitenbush Oregon, organized by Rosemary Gladstar and California School of Herbal Studies. At that time I was the only herbalist there from east of the Mississippi river. I remember sitting in this large room, in a semi-circle with 69 other people, sitting on the floor, looking at all these faces and realizing: these are my people. It was such an incredible experience to feel a part of something.

“…So many herbalists live truly inspired lives”

If we go back 40 or 50 years, being a herbalist was not something that was widely known, appreciated, or in any way accepted. If you told your high school guidance counsellor that you wanted to become a herbalist, they would have looked at you like you had lost your mind. The reality is that people who took up this work were very isolated, but eventually as we got to know each other, we found out there was an amazing community of creative, curious and interesting people working with plant medicine. So many people in the herbal community were multifaceted and amazingly talented. Our herbal elders, some of whom are no longer with us. Michal Moore, for instance – he was a classically trained musician, and performed on wind instruments in the LA symphony orchestra. Michael Tierra is a concert pianist. Jillian Stansbury is a polymath, she is brilliant in so many ways; she is a musician with an incredible voice, and for fun in her spare time she studies things like quantum physics. It is such an interesting group of people: poets, artists, musicians, as well as herbalists, and I think that speaks to the heart of many herbalists, to the fact that so many herbalists live truly inspired lives. Nobody gets into herbal medicine because they think they are going to become rich and famous. That’s not the motivation. There are people who become well known and make a good living, but that is not the underlying motivation. To a great degree, people fall in love with plants and with the idea of helping others, and that is the real motivation.

Even though I’m not in full time practice anymore I still see patients. I haven’t charged people for helping them since sometime in the 1980s. I just help people. It seemed it was not right to charge people to make money off of their suffering. I’m not trying to suggest that it is wrong for others to charge for their services. My income comes from teaching, writing books, consulting with physicians and industry. When somebody comes to me and they say ‘I need help’, I just help them. For me that is a big part of reciprocity. So much of what I have learned over half a century was shared with me freely and I love sharing it with other people. Whenever I can, and whenever people are interested I’m always happy to share what I have learned. You know the old expression: we stand on the shoulders of giants. It’s true. So much of what I know comes from traditional Chinese medicine, from Southeastern traditions in America, the Eclectics, the Physiomedicalists, from the practices of Ayurveda and Unani-tibb. These traditions are 100s or even thousands of years old. They all inform what I do and what every other herbalist does. Nobody discovered all of the things that St. John’s wort can do by themselves. It has been a gradual process of disclosure taking place over millennia. As we use herbs in clinical practice, we gain unique insights and share them and our collective knowledge just continues to grow. This too is reciprocity. I see so much of this in the herbal community: reciprocity, generosity, creativity. And those are wonderful things to have as a foundation for a community of people who are in most cases trying to make a difference in the world by making people’s lives better.

Accomplishments in the world of herbal medicine

Everything Herbal: What would you identify as some of your major accomplishments in the world of herbal medicine?

David Winston: The greatest thing that I personally have done as a herbalist is in the area of education. As a practitioner, there are a lot of people I have worked with and helped. Sometimes people say: ‘you’re a healer.’ I’m not, the herbs are the healers, the Creator is the healer, I’m not a healer. At best, I’m an educator. Whether I’m educating on a one to one basis in my role as a clinician or educating students about the wonders of herbal medicine, it’s a deeply fulfilling role. I may be giving an herb walk and sharing with people who may have never been exposed to herbal medicine before, or lecturing to my two year herb studies program, where thousands of people have studied. The program is designed to teach people to become clinical herbalists. Half of the students who come into this program are already medical professionals, MDs, NDs, DOs, nurse practitioners, acupuncturists, veterinarians, and other health care professionals. The other half of my students are people who have been self studying herbal medicine for years or even decades and they really want to improve their skill level so that they can help people in more profound ways. Adding herbs to your toolbox, so to speak, makes a huge difference. It’s not that herbs can do everything – they can’t. But where herbal medicine is strong tends to be where orthodox medicine is weak and vice versa. When I say herbal medicine, understand that in my view herbs are not foundational. What do I mean by that? The foundations of health are a healthy diet, adequate good quality sleep, exercise, healthy lifestyle choices, and stress reduction. Those are the foundations of health. Any herbalist or any practitioner of any sort that is not working with all of those things is missing the boat. Nobody ever became sick because of St. John’s wort deficiency. The idea is that we want to do everything we can to help people. We start with the foundations of health, and when we get to therapeutic modalities herbal medicine is incredibly useful. Most herbs are relatively nontoxic, there is a fairly low rate of clinically significant adverse effects especially if you know how to use herbs appropriately.

“It is more important to know the person who has the disease, than the disease the person has” – Hippocrates

In my first two year herb studies program I had two students. That was in 1981. I was thrilled that anybody else wanted to learn about medicinal plants. Today we have students from all over the world. My goal in teaching people is not to teach them to be good herbalists; my goal is to teach them to be great herbalists. When I say great I don’t mean as a comparison to someone else, I mean each person in their own unique way. Each of us is capable of greatness based on our unique knowledge, intelligence, skillset, passion, creativity; each of us has the ability to take this information and do unique and wonderful things with it. But I also believe that if you really want to be a great herbalist, then there are a few things you have to understand and the first thing is to stop focusing on treating disease. Hippocrates is believed to have said more than 2000 years ago: “it is more important to know the person who has the disease, than the disease the person has”. He was right then and he’s right now. What he means by that is if you have 5 people, all diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, the treatment for each will be based upon their unique requirements as individuals. From an orthodox medical perspective the treatment for a given disease seen in different individuals is often the same. As an herbalist, I look at 5 unique people. Yes they all have rheumatoid arthritis, some are female, some are male (hormonally speaking), some are old and some are young, some have underlying GI issues, some have circulatory issues, some have cardiovascular issues, and the more you can treat the person who has the disease, the more effective your protocols are by far. If you have somebody with bacterial meningitis, don’t call the herbalist, reiki healer or chiropractor. You want them in the hospital with iv antibiotics. It is not about creating a dichotomy between orthodox and complementary medicine. They both have their strengths and weaknesses. The key is helping students to understand how they can most effectively help people.

46 years ago I was introduced to the concept of energetics by one of my early teachers who in my opinion is one of the great herbalists of the 20th century: William LeSassier. William is the person who introduced me to herbal and human energetics, which allows the practitioner to match specific herbs to the person. When you focus on the disease, you are missing out on the energetics and the constitution of the patient, which is required if you are to treat the person. William also introduced me to Chinese medicine and Chinese herbs, as well as a lot of obscure western herbs like evening primrose. Everybody who is reading this is probably is saying ‘evening primrose seed oil, I know about that.’ But I’m not talking about that, which I don’t think is even all that useful. I’m talking about the herb Evening Primrose (Oenothera biennis), the leaf, flower or root bark. It is a common native weedy plant, it is an incredible medicine used for things like GI-based depression and inflammatory bowel disease, it’s a wonderful medicine that almost nobody knows about. I credit William again with changing my mind and my entire direction in herbal medicine. Before what I had encountered was along the lines of: this herb is good for headaches, this herb is good for depression, etc. You see this all of the time with these little soundbites of information about herbal medicine that get circulated in books, classes and the internet. For example, St. John’s wort is the depression herb, Saw Palmetto is the prostate herb, or Black Cohosh is the menopause herb. There is one problem with each of those statements: they are wrong, wrong and wrong.

Take St. John’s wort: when I teach on the differential treatment of depression and anxiety, we differentiate more than 14 types of depression based on the underlying pathophysiology. When you treat a person who is depressed, you need to understand what is actually causing the depression. Is it GI-based depression, inflammation-induced depression, old age- induced depression, blood sugar dysregulation-induced depression? The studies show that most pharmaceutical medications like SSRIs and SNRIs work about 40% of the time. St John’s wort also works about 40% of the time if you just give it for the disease entity depression. But if you actually treat the person who is depressed, I can say from my own clinical practice (there are no studies on this) 60 – 65% of my patients with mild to moderate depression have very significant improvements, even to the point where they don’t feel they are depressed at all anymore. This is huge when compared to 40%. Is it perfect? No, but the point is that we have a significant improvement when we are treating the person rather than the disease.

“…That we have helped to teach people how to be great herbalists, is something I’m very proud of.”

For me I think the accomplishment I am most proud of is to be able to look around and see a much bigger herbal community than existed when I first started. People who have been part of my programs are a piece of that, and to know that we have spread that information, that we have spread that knowledge, that we have helped to teach people how to be great herbalists, is something I’m very proud of. Today I look around the world and there are people who have graduated from my program who have their own schools, who are well known herbalists that have written many books, who have these incredible practices. Of course it is not just because of my program that they accomplished these things, it was just a piece of their development. But the fact that I can help people with that one piece to me is a blessing. It makes me very proud to be a part of this community and to continue to pass on what I have learned, to share it and have our traditions continue.

“In the US we spend more money per capita on healthcare than any other country in the world”

Some years ago I was the keynote speaker for a conference called the Florida Herb Conference, organized by Emily Ruff, a wonderful herbalist. I called my speech ‘I Have a Dream.’ I started off by saying ‘you’ve heard these words before by someone far more eloquent than I, but I have a dream too, and my dream is that within my lifetime I hope to see a time where almost every mom, dad, grandmother and grandfather knows basic kitchen herbalism for their family, where there are community herbalists in every community and clinical herbalists available in any clinical setting.’ Why? I believe without a shadow of a doubt, and I’m talking now about the US, (in Canada things are a bit different) in the US we spend more money per capita on healthcare than any other country in the world yet we have worse health outcomes. We are behind every developed country when it comes to infant mortality and life expectancy. We are close to the top when it comes to obesity and cancer, but in all of the health measures that you want to be good at, there are many underdeveloped countries that have much better numbers and outcomes than we do. I believe that really well done herbal medicine can help us create a sustainable practice of medicine not only in the US but around the world. There are countries like India, China, Japan, even Germany where herbal medicine is part of mainstream medicine and it allows them to have a more effective medical system with fewer adverse effects and a greater number of options. That’s my dream. That’s my goal. To make this not alternative, but a part of the mainstream, not just mainstream medicine but mainstream understanding and knowledge. I hope that at some point everybody knows basic herbs to use for common ailments. Most people already know that if you are constipated you can take prune juice or that you can use aloe for a burn. There are lots of things like that that people could learn and use at home, thereby preventing for example the unnecessary use of antibiotics. Antibiotic resistance is a huge problem today. How many times could we give somebody antibacterial herbs for a UTI and thereby avoid having to use antibiotics altogether. How many times do we see people being given antibiotics when they have a viral infection and they don’t work at all? Yet we have herbs that would be perfectly appropriate in that situation. Are herbs the answer to everything? Absolutely not. Are they an answer that can help us to create a better practice of medicine, one that is better for the planet and better for the people and animals on the planet? Without a doubt.

“As a clinician one of the greatest gifts that you can give yourself is to keep an open mind.”

Everything Herbal: I’ve been fortunate to go to many herbal conferences over the years and have heard so many speakers. Out of all the speakers I have listened to, I can still see you on our stage at the Restorative Medicine Conference. I was in the front row doing the introductions and you opened for us. You sang a song, and even though I had no idea what you were singing, it penetrated my soul and made me cry instantly. To me in that moment, and even now reflecting back after all of these years, it was a profound healing experience. I still even get emotional about it because I have no idea what happened in that moment, but I know that something happened. You were the portal for something awe inspiring to come through, and it was a great gift.

David Winston: As I said earlier, I think that the plants are the true healers but many people in the herbal world have gifts that go beyond herbal knowledge. Many are inspiring, wise, and stewards of the green world. In addition to being an herbalist, I write poetry, I sing, I garden and love photography. These things bring me pleasure and help me to see the world in a different way and express myself creatively. I always wished I was better at visual arts. Unfortunately I’m not a very good artist, although both of my parents were very good artists. I have some significant visual, hand/eye coordination issues. I was born severely visually impaired and I didn’t actually see until I was about 18 months old. I had 3 surgeries on my eyes by the time I was 5. There are certain things that I just don’t do as well as most people do. When I was a child there was no diagnosis of dyslexia, or ADHD, although I would have been diagnosed with both if I was born 15 years later. People think of them as disabilities, and they are challenges for sure. But they also bring unusual strengths and skills if you are fortunate enough to have the necessary help navigating the differences. I was talking about this before when I talked about being great in our own unique ways. I don’t consider myself great in any particular way but I am striving to be the best that I possibly can be in every single thing that I do. Now obviously I fail more than I succeed but you keep trying, you keep trying to grow and become a better person, clinician, parent, friend or partner.

As a clinician one of the greatest gifts that you can give yourself is to keep an open mind. I always tell my students the worst disease a practitioner can get is what I call “hardening of the mind”, where you start to believe that everything you know and think is true. I am partially kidding when I say this, but I always tell people after 53 years of studying herbal medicine I now feel comfortable calling myself an advanced beginner. Why? It doesn’t matter how much you know, it is still a fraction of what there is to know. You always want to stay open to the process of continuing to learn. This is true for anybody, whether an auto mechanic, a scientist, a farmer, a physician, an herbalist or an artist. It is openness to creativity, to new ways of seeing, thinking or being that allows us to grow professionally and as human beings. How many examples do we have of musicians who become famous for a certain style and their next album comes out and its totally different and their fans don’t like it. But as an artist, there is something that pushes you to grow and experiment. To stay stagnant and just keep doing the same thing over and over and over again doesn’t serve that purpose and ultimately doesn’t serve the art. As an herbalist or as a clinician you have to stay open minded to the fact that everything you believe is true is subject to change. That doesn’t mean it will change, but it could. When we get dogmatic and when we start allowing ourselves to be put up on a pedestal, we are in dangerous territory. If you are up on a pedestal and everybody is looking up at you, invariably you are looking down, its an uncomfortable place to be. Something about human nature is that while people love putting others up on pedestals, they also love tearing them down.

“… Recognize that the plants are the healers.”

It is important to stay humble, to recognize that the plants are the healers. Art, music and creativity are also great healing forces. So is vulnerability. Recently in class a student asked a question and it was about somebody going through a really hard time. I didn’t say to them ‘oh you should do this and that’; instead, I allowed the experience that was shared to touch me, just like that song touched you. The experience of suffering that was related in class touched me deeply and reminded me of an experience in my own life. It was a very humbling experience; being able to share vulnerability and fragility with others allows people to recognize and connect in to their own pain, their own suffering, their own fears, their own doubts. When we can do this, we begin to recognize that we are not alone in our sufferings, and not alone in the world. In any traditional form of medicine, there is no separation of body, mind and spirit. Of course, there are times when you have a simple wart and I don’t need to know what’s going on with you emotionally. I can simply say, ‘here try some celandine, put it on twice a day’ and more often than not the wart will disappear. But if we are talking about more serious health issues like depression, anxiety, autoimmune disease, cardiovascular disease, all of these conditions don’t just affect the body, they also affect the mind, the soul and spirit too. All of these levels are deeply interconnected, they are all part of the same organism.

This is also where complementary medicine can fall short. There was a diagram created by Kenneth Pelletier in the 70s of three interconnected circles labeled body, mind, and spirit. That is supposed to represent holism. There is only one problem with that: it is not big enough. If you put a big circle around those three interconnected circles, that circle is family. Then there is another even bigger circle around that, and that’s community. And then there is yet another circle around that, and depending on what name you want to give it, that’s God, the Creator, Nature, Gaia, whatever concept you want to put in there. What the body/mind/spirit level of the diagram recognizes is that we are interconnected within ourselves, but what it fails to recognize is that we are also connected to everything else, to everything outside of ourselves. When I teach my class on depression, one of the things I always tell people about depression is that it can be a learned behaviour. If you grew up in a household where one of your parents was chronically depressed you stand a 50% chance of being chronically depressed yourself. If you grew up in a household where both of your parents were chronically depressed you have about a 100% chance of being chronically depressed. As an infant and young child you don’t know what is healthy behaviour and how things in the world can or should work. Whatever behaviour that is modelled for you becomes your norm. If the people around you are always depressed, always anxious then that is what you come to believe is normal and desirable.

“To feel that you have a place in the world, to feel connected is essential to health and wellbeing.”

There is also a part of the brain known as the mirror neuron network. If, for example, your significant other is chronically depressed or anxious, the chances of you becoming chronically depressed or anxious skyrockets. Why? Because this part of the brain which allows us to feel empathy, sympathy and connection to others, triggers deep feelings and emotions in us that are indistinguishable from our actual emotions. For most of us when we see somebody who is suffering and we feel it, not just ‘oh that’s too bad’, but when you really feel it ‘oh my god thats terrible’, you want to help and do something. That is the part of the brain that mirrors the behaviours of others, and if you are in a relationship or even living in a place where other people are experiencing those things on a regular basis, it is very hard for you not to respond and get pulled into that mindset, whether it is anxiety or depression or hopelessness. We are deeply affected by others, and in many indigenous traditions if somebody is ill you don’t just treat that person, you treat their entire family. The next circle after family is community, and so many of us no longer live in functional communities. We are isolated and separated, and this causes major issues for human beings, who are innately tribal. By using the word ‘tribal’ I do not necessarily mean a native nation, although that is certainly tribal. I certainly don’t mean the terrible tribalism that we have in the US: red vs blue, liberal vs conservative, etc. That is tribalism at its worst. What I mean is that we feel the need to belong. Unfortunately that seems to be one of the appeals of so many of these hate groups that are out there now. You have people who don’t feel like they belong anyplace, who feel like outcasts and feel scorned and belittled by society. Often, they find acceptance and comradery in such movements and they get caught up in a group that is bounded by hatred. To feel that you have a place in the world, to feel connected is essential to health and wellbeing. I talked about it earlier when I was describing sitting in a room with 69 other herbalists at a young age and feeling that I had finally found my people. Being able to find others who accept us for who we are, and participating in a functional, healthy community; this is unfortunately so rare in today’s world.

“You are part of something bigger than yourself”

The last circle, relating to one’s relationship to a higher power (again, whatever name and concept you have of this is fine), helps us to recognize that we are a small part of something much greater than ourselves, something that pulls us out of our ego, pulls us out of our fear, doubt, isolation, separation and out of our belief that the world begins when we are born and ends when we die. This perspective reminds us that yes, each and every one of us is sacred and blessed and yet each one of us is a speck of dust. We are both magnificent and insignificant at the same time.

This is the importance of having a spiritual practice, whether you have a religion or not. The connection to a higher power is the essential piece. If you don’t believe in an entity, you can achieve the same thing through Nature, Gaia, it doesn’t matter, as long as you believe you are part of something bigger than yourself. That is a really useful and helpful orientation for human beings to have; it is arguably what allows us to become human beings in the first place. If you ever go some place where there is almost zero light pollution, and I’ve been to places like this in the mountains of North Carolina or in parts of Canada, New Mexico, Maine Ireland and Costa Rica, and you look at the night sky it can be breathtaking. Instead of seeing a few bright stars or planets, you see the entire milky way. Sadly many people have not had this experience today. When you look up at such a sky it is magnificent, you enter into a state of awe. It makes you feel so small but at the same time connected to something so vast. To me that is the power of healing, those moments that literally take your breath away where you’re just in awe that the world is so magnificent, so beautiful. For many of us that experience is so far away from our daily lives, and we lose sight of it, we lose sight of the joy and the newness and the discovery and the wonder of the world that we were born with as children. For many people today, the world is not a place of wonder. It is a place of fear, hurt, prejudice, or inhumanity. I think that herbs, nature, meaningful ritual, forgiveness, compassion and love can contribute to the healing this core wound of disconnection that many of us suffer from today.

“Originally I was going to be a farmer…”

When I was in high school I used to have an organic farm. It started off as a 20 or 30 by 80 foot plot and eventually I got more land down the road. I had two acres and a roadside stand where I sold organic vegetables in the summer, in the late 60s and early 70s. Originally I was going to be a farmer, I was growing herbs and vegetables, and the one thing I didn’t grow was flowers. I thought who cares about flowers. Today I realize I was mistaken. While I still grow many herbs and vegetables, today I love flowers. And three of my favourites are fragrant roses, irises, and peonies. The irises I grow are old fashioned fragrant irises. The modern ones often have no odour, but the old varieties are really fragrant and they almost smell like a combination of cinnamon and bubble gum, a very unusual combination. Every year, when the irises start blooming I go out every single day and stick my nose in those flowers and just inhale deeply. Think of it as primitive aromatherapy. When the peonies are in flower, I go out there and I smell them too. The roses start blooming before any of the others and continue blooming in through the autumn. When I go out and smell these flowers I am so uplifted by their odours. Yes the night sky in a place where there is no light pollution is spectacular, but smelling a fragrant rose is also magnificent. Smelling one of those fragrant irises is magnificent. Magnificent things, healing things can be huge things that literally stop you in your tracks, as well as little things that for a moment bring you back to a place before you were weighed down with all of your worries, to a simpler, better place of healing.

Let’s talk a bit more about the integration of herbal medicine with the conventional medical system…

Everything Herbal: …It’s an important issue that many people don’t think about in a lot of detail. It seems like such a distant possibility. What are some ways that this might come about? What are some steps that practicing herbalists can take to do what is necessary to get to a point where the practice of herbal medicine is widely accepted, integrated, and thereby helping a greater number of people?

David Winston: Often in the herbal/alternative/complementary medicine community there is an attitude of us vs them. Tribalism, not the good kind. The mentality is that the medical establishment and the pharmaceutical industrial complex are out to get us. Granted, pharmaceutical companies are not big fans of herbal medicine because it certainly cuts into their profits. Between 1995 – 1998, many of the big pharmaceutical companies jumped into the herb market and came out with their own lines of herbal products. Within a few years they all dropped it, they realized there was simply not enough money to be made no matter how good their products were. It wasn’t close the level of profit that they got from their pharmaceutical medicines. It is true that orthodox medicine is not necessarily open to herbal medicine, but my belief is that mostly what we are dealing with is a lack of knowledge. Doctors go through this incredibly rigorous training over so many years, and when they graduate they have limitations depending on what state in the US they are practicing in. There are regulations, as well as insurance and liability issues, that keep people in their own little silos. Firstly, if we are to think about this issue, education about herbal medicine is vital. During the period between 1995-1998 herbs were hot and they were in the media all of the time. I was getting 4 or 5 phone calls a week from physicians saying ‘you know I’m interested in these herbs, I want to learn more about them.’ The media has this tendency where if something is wonderful then eventually the pendulum turns and it becomes something of suspicion. And sure enough, around 1998 we started seeing all of these articles both in the medical literature and in the popular press about herbs being dangerous.

“…One of the things that happened was that more people who were taking pharmaceutical medications were taking herbs simultaneously.”

With the increase in the use of herbs during this period one of the things that happened was that more people who were taking pharmaceutical medications were taking herbs simultaneously. There were legitimate reports of problems like herb-drug interactions and adverse effects. For example, St. John’s wort, which is a very useful plant for many different health issues, but is also the “poster child for herb-drug interactions”. That is because St. John’s wort not only affects phase 1 liver detoxification via the CYP1A2 and CYP3A4 and CYP2D9 pathways, which are enzyme isoforms that the liver uses to metabolize and break down pharmaceuticals as well as environmental toxins. It is also because St. John’s wort affects phase 3 detoxification, which takes place in the kidneys and the bowel, via the p-glycoprotein (P-gp) drug transport system. The fact that St. John’s wort up-regulates and/or down-regulates both of these systems means that it can have a significant potential for interactions with some pharmaceuticals. The good news is that, with the exception of St. John’s wort and a handful of other herbs, herb-drug interactions turn out to be fairly rare and clinically significant events, meaning they can cause a dangerous interaction, are actually even rarer still.

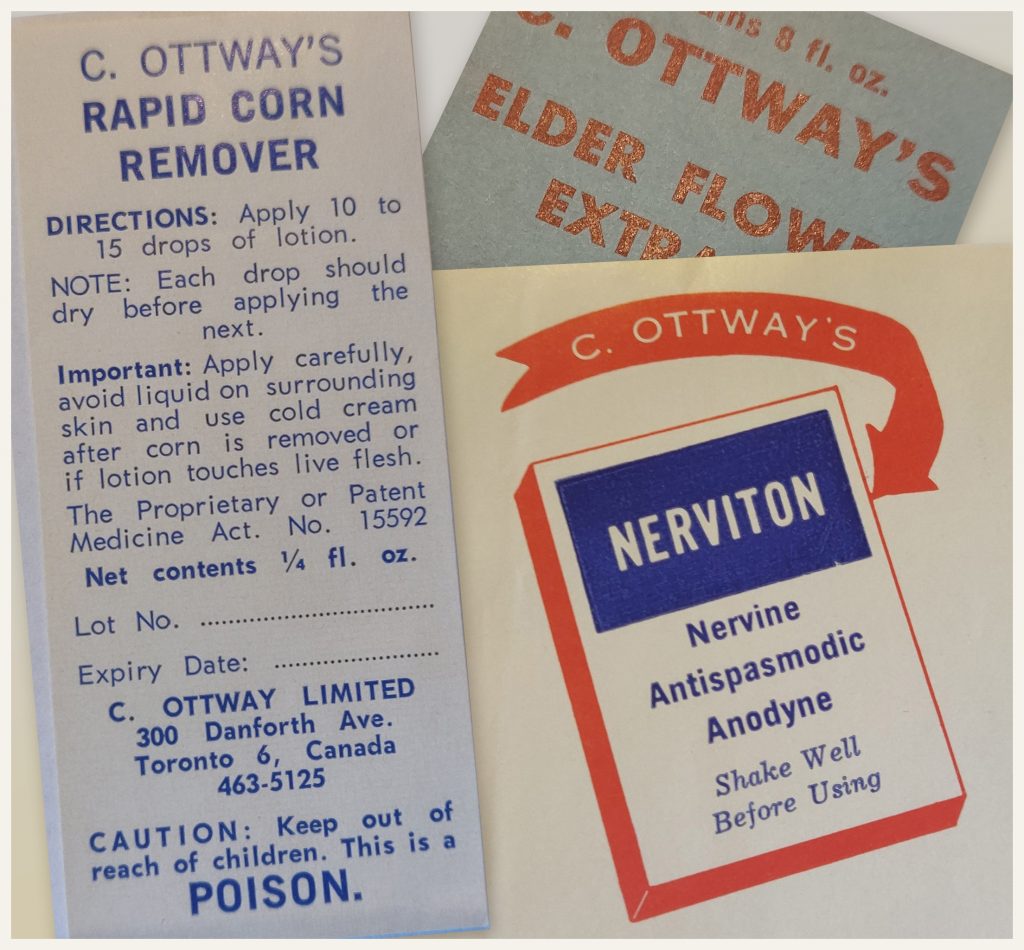

This is not to say herb-drug interactions can’t happen, because they can, but the danger in most cases is overstated. When looking at herbal safety if we look at statistics, taken from American studies, the number of deaths from properly prescribed pharmaceuticals (not including overdoses) is between 95 to 120 thousand people per year. The number of Americans who die from over the counter, supposedly safe NSAIDs, is 17 to 18 thousand per year. The number of Americans who die every year from food, everything from food poisoning to choking to anaphylactic allergic reactions, is about 9 thousand. These are somewhat older statistics, they could have gone up or down a little bit within the last decade. The number of Americans who die from herbs, in the last year that we have any information about this, was 37. That was before Ephedra was banned, and almost all of these deaths were from Ephedra. Is this to say that herbs are entirely safe? They are absolutely not. But this statement needs to be put into perspective.

“We can divide herbs into three categories: food, medicine, and poison.”

Your food herbs are generally safe, unlikely to have significant adverse effects and they can generally be used in significant quantities. These are things like blueberries, cinnamon, ginger and garlic, but also mild gentle herbs like lemon balm, chamomile, hawthorn berry, etc. We are not talking about allergies, because with German Chamomile there is a report in the literature of a person who had very severe ragweed allergies having a cross-reactivity reaction to chamomile, developing anaphylaxis and dying. There is one case in the entire literature out of millions of cups of Chamomile being drunk every single day. For that one person Chamomile was not safe, but anyone can have an allergic reaction to any food, any drug, any herb, any cosmetic so that is a separate issue. Your medicines on the other hand are stronger acting, they are to be used with more knowledge and usually for a limited period of time. These are herbs like Goldenseal or Ephedra back before it was banned. You don’t just take these everyday because they are good for you. You take them because you have a specific medical issue usually under the guidance of a trained clinician. And then finally your poisonous herbs should be left alone and only used by clinicians who are trained to use them, they have the potential for overt toxicity. We can think of digitalis, for instance.

Understand that what we need to do is to really educate people, not just mom and dad, grandma and grandpa, but the medical profession as well. Medical doctors don’t get much if any training in herbal medicine. I do teach at a couple of medical schools, where they get a one class introduction to herbal medicine but even that is the exception. Most physicians have no information, and what they are reading in the literature often contains a lot of incorrect information. The literature is often based on fear, many of the purported herb-drug interactions are based on in vitro studies meaning it is done in a test tube or petri dish and those rarely pan out when we start doing in vivo studies (in a living organism). Then there are many things in the literature that are a single case reports, meaning one person took something and had a bad reaction to it. If that was a pharmaceutical that would never get into a journal. That happens all of the time and you cannot ascribe causality to someone taking something and having a reaction. The reaction could have occurred for many reasons, or it could be an idiosyncratic reaction. If it is an herb that someone has a reaction to however, that will get put into a journal. Then it becomes part of the literature, and it reinforces the view: ‘oh, see herbs are dangerous.’

“Where herbs are strong tends to be where orthodox medicine is weak and vice versa.”

As I said earlier, where herbs are strong tends to be where orthodox medicine is weak and vice versa. If you have someone with chronic skin problems who has been to 20 dermatologists and nothing helps, that is one of the places where herbs shine. If you have somebody with treatment resistant mild to moderate depression (severe depression is very treatment resistant no matter the approach), who has been given various SSRIs and they didn’t work or caused significant adverse effects, herbs can work beautifully there. Herbs are not only effective in many cases for prevention, they can be used in treating many issues where orthodox medicine offers few options. There are some major issues in medicine today, one of them I mentioned earlier is drug resistant bacteria. Most people have no idea that there are studies showing dozens and dozens of herbs that can be given with an antibiotic and it shuts down the multiple drug resistant (MDR) pumps in the bacteria allowing the antibiotics to become effective again. Herbs can work incredibly well in conjunction with orthodox medicine. The more we can get out there and educate people and share this information the better.

I would like to point out though that there are many issues holding us back in the herbal community. One is that most of us don’t know how to do research. As herbalists we need to learn how to do simple, basic but good research and start publishing the results. What happens in your office is interesting but that is empirical, it is not proof. In addition to herbalists learning how to do research, herbalists need to stop thinking in a silo and start reaching out to other practitioners. Throughout my entire career, I’ve always worked with other practitioners. I act as a consultant to over 100 medical doctors and naturopathic physicians throughout the US, Canada, and Europe, and I love that relationship. I learn new things all of the time in this role. I don’t have the answers to everything and they don’t have the answers to everything, so that kind of cooperation creates movement, it helps get the knowledge out of the silo into the mainstream.

“We need to start having a better dialogue within our own community.”

One last thing I’d point out about the herbal community, there is often a significant lack of consensus about what things mean. I remember Rosemary Gladstar saying ‘the only thing herbalists agree on is not to use aluminum cookware.’ She was basically right. One of my books is called ‘Adaptogens: Herbs for Strength, Stamina and Stress Relief’, the second edition came out in 2019 the first in 2007. There were several reasons I wrote the book. One is that I got tired of people calling herbs adaptogens that aren’t. I also thought it was really inappropriate that people were using this term adaptogen to mean whatever they wanted it to mean. I had someone ask me ‘why do scientists get to decide what an adaptogen is?’ It’s because they created the whole idea and concept! The word and concept of adaptogens didn’t come from TCM, or Ayurveda, or from the herbal community – the concept of adaptogens came from Soviet research starting in 1947. They get to define the concept because they came up with it. Adaptogens are not the same as a rasayana in Ayurveda, they are not the same as qi tonic or kidney yang tonic in TCM. There is some overlap, but an adaptogen is its own thing. There is a lot of sloppiness in my opinion especially when it comes to nomenclature and terminology in the herbal community. 10 herbalists will give you 10 different definitions of an adaptogen or even worse, an alterative. If we can’t even communicate amongst ourselves, if we can’t create a consensus about what our terminology means, it becomes very difficult to communicate to someone outside of the herbal medicine world. We need to start having a better dialogue within our own community. I’m not suggesting that we become homogenized in our thinking, I don’t mean that we all have to use the same herbs in the same ways. I’m not talking about standardization. But we do at least need a consensus on terminology, I believe this would be a very useful thing.

The funny thing is that with adaptogens, there are only 8 or 9 herbs that are actually well researched and fit the definition. There are another 5 that I’d call probable adaptogens, the evidence is weaker but suggests they may well be adaptogens. And then there are another 12 or more that I’d call possible adaptogens, where the evidence is actually very weak. As herbalists we need to up our game and come out and say ‘we have something worth knowing about’ instead of just sitting there saying ‘I’m just going to do my own thing.’ Anybody who is an herbalist knows they have something of value to share, so let’s make the work we do stronger, let’s continue to educate ourselves, let’s grow our knowledge, our community, and then bring it out into the world and say: ‘here is this incredible gift that we’d like to share with you.’

To conclude…

Everything Herbal: What is something heartfelt that you could share with new students or people who are just getting into herbal medicine? You speak of your love of herbs, but tell us about how this love shows itself.

David Winston: I don’t know if this is a direct response to your question, but I mentioned earlier that if I was born later I would have been diagnosed with both dyslexia and ADHD. I tend to get bored or distracted easily, unless a topic is deeply interesting to me and I can continue to learn about it. To me one of the blessings of herbal medicine, and this is true of medicine in general, is that as I said earlier I still only know a little bit of what there is to know. And I am just as enthusiastic and excited about herbs and herbal medicine today as when I first fell in love with plant medicines. The passion has not left me. When I am walking on a trail in the woods and I come across a plant that I’ve never actually seen before except in a photograph, it is just enthralling, it is like meeting my new best friend. It doesn’t have to be a showy plant. In the UK there is this plant called Pellitory of the wall or Pellitory on the wall. I have tried growing it here in the US and I’ve had limited success getting it to grow well and spread. It is used as a kidney trophorestorative, basically a food for the kidneys. I moved to my present home with my wife in 2014, and there is this plant I did not know growing on my property. I saw it multiple times and it wasn’t very showy, it’s green, you almost can’t see the flowers, and last year there was a great deal of it. I was going to go pull it up but then I thought to myself, I should look it up first. I discovered that it is called Pennsylvania Pellitory. It is in the same genus as the plant from the UK, but a different species. Immediately my reaction was ‘oh my goodness, it is growing right under my nose, and it really likes growing on rock walls just like the Pellitory of the wall in the UK!’ My questions then lead me to investigate, but I don’t have the answers yet. I found no ethnobotanical history of using this plant. Here is a relatively obscure plant with no history of use in the US, related to this English plant that I’ve wanted to use for years but haven’t had easy access to. So now I’m very excited and trying to find out any of the chemistry of the plant so I can compare it. I’ve tried tasting it (I do know it is not toxic!) to see if there is an organoleptic similarity, but unfortunately the English Pellitory is not very strong tasting or smelling. Now I am wondering if this can be used in a similar way to the other plant, and the answer at this point is that I have absolutely no idea. I don’t have access to phytochemical testing, so I have to see if there is any data or literature I can find, but the possibility of discovering an analog to an affective medicine makes me want to learn more.

People say if you learn something new it is a good day, and that is really true for me.

What can I learn today that I didn’t know yesterday, what new plant might I come across, what new use can I find for this herb or that herb, all of that to me is thrilling and I will continue with this work as long as I’m alive and mentally able. I have one of the largest private herbal research libraries in North America and I am constantly going back and looking at old books. I have books from the 1580s through to the present. I will take an old book off the shelf and be surprised by something I didn’t know, just as I can be surprised by some new research that comes out. The same can happen in class, when we are going over a case history and somebody says something that I didn’t know or think about before. It is just marvelous for me to be able to continue to learn. By continuing to learn, I am better able to share, better able to help others and hopefully in the process I contribute to making the world a better place for us all.

David Winston, RH (AHG) is an Herbalist and Ethnobotanist with 53 years of training in Chinese, Western/Eclectic and Southeastern herbal traditions. He has been in clinical practice for 46 years and is an herbal consultant to physicians, herbalists and researchers throughout the USA, Europe and Canada. David is the founder/director of the Herbal Therapeutics Research Library and the dean of David Winston’s Center for Herbal Studies, a two-year training program in clinical herbal medicine. He is an internationally known lecturer and frequently teaches at medical schools, professional symposia and herb conferences. He is the president of Herbalist & Alchemist, Inc. a manufacturer that produces herbal products that blend the art and science of the world’s great herbal traditions.

In addition, David is a founding/professional member of the American Herbalist Guild, and he is on the American Botanical Council and the American Herbal Pharmacopoeia Advisory Boards. He was a contributing author to American Herbalism, published in 1992 by Crossings Press, and the American Herbal Pharmacopoeia (AHP) , 2000-2018, the author of Saw Palmetto for Men & Women, Storey, 1999 and Herbal Therapeutics, Specific Indications For Herbs & Herbal Formulas, HTRL, 2014 (10th edition) and the co-author of Adaptogens: Herbs for Strength, Stamina and Stress Relief, Healing Arts Press, 2007 & 2019 2nd Ed, and Winston and Kuhn’s Herbal Therapy and Supplements; A Scientific and Traditional Approach, Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott, 2008. David has also published hundreds of articles in medical and botanical medicine journals and conference proceedings. He is also a member of the AHPA Expert Advisory Council that created the second edition of the Botanical Safety Handbook, CRC Press, published in 2013 (3rd edition in press).

In 2011 David was a recipient of the AHPA Herbal Insights award. In 2013 he received the Natural Products Association Clinicians award and was awarded a fellowship by the Irish Register of Herbalists. In 2018 he was the Mitchell visiting scholar at Bastyr University and in 2019 he was awarded an honorary DSc degree from the National University of Natural Medicine (NUNM) in Portland, OR.

You can find David online at davidwinston.org and his herbal training program available at herbalstudies.net

Photos provided by Serena Mor (excluding David’s first photograph)

Magic, Healing & Ritual: Herbal Tradition in the Italian Renaissance

Angels, Demons, Herbs and Magic

The ancient, and now largely lost and forgotten, tradition of illuminated herbal manuscripts can tell us much about the practice of herbal medicine throughout antiquity. It was not uncommon for such manuscripts to contain drawings of angels and demons, mythological figures and beings of the celestial hierarchies. Witchcraft and magic were taken to be very serious matters, not only when it came to cultural and religious belief systems, but also when considering the proper training of a physician. As one author writing on traditional Italian healing systems in antiquity has commented:

“Physicians were educated with the notion that drugs had occult powers to affect the body in special ways. It was common belief that demons invaded the soul, and that certain herbs had the property of chasing away devils and demons” (Silberman: 1996).

Expert Italian Renaissance physicians were required to be competent in astronomy and astrology “since the position of the celestial bodies contributed to the occult qualities of a medicinal herb” (Silberman: 1996). The Renaissance, as reflected in the writings of prominent philosophers of the time such as Giordano Bruno and Marsilio Ficino, saw a resurgence of pagan sensibilities. Renaissance thought and imagination embraced an animistic worldview that threatened the established, conservative branches of Christianity and their associated medieval superstitions. As the archetypal psychologist James Hillman writes:

“Renaissance animism led to pluralism, which threatened Christian universal harmony. For when inner soul and outer world reflect each other as enlivened souls and substances, and when the images of these souls and substances are pagan, then the familiar figures of Christianity diminish to only one relative set among many alternatives.”

This co-reflection or mirroring of the inner soul and the outer world are the life-stream of the ancient pagan and Renaissance herbal medical traditions of Italy and surrounding regions. This conception of a pluralistic world and of the enlivened human soul seen as a microcosmic reflection of the greater soul of nature helps us to understand the associations and correspondences that were made between particular herbs, supernatural, celestial, and divine beings, and the actions of the planetary bodies in the medicine of the time.

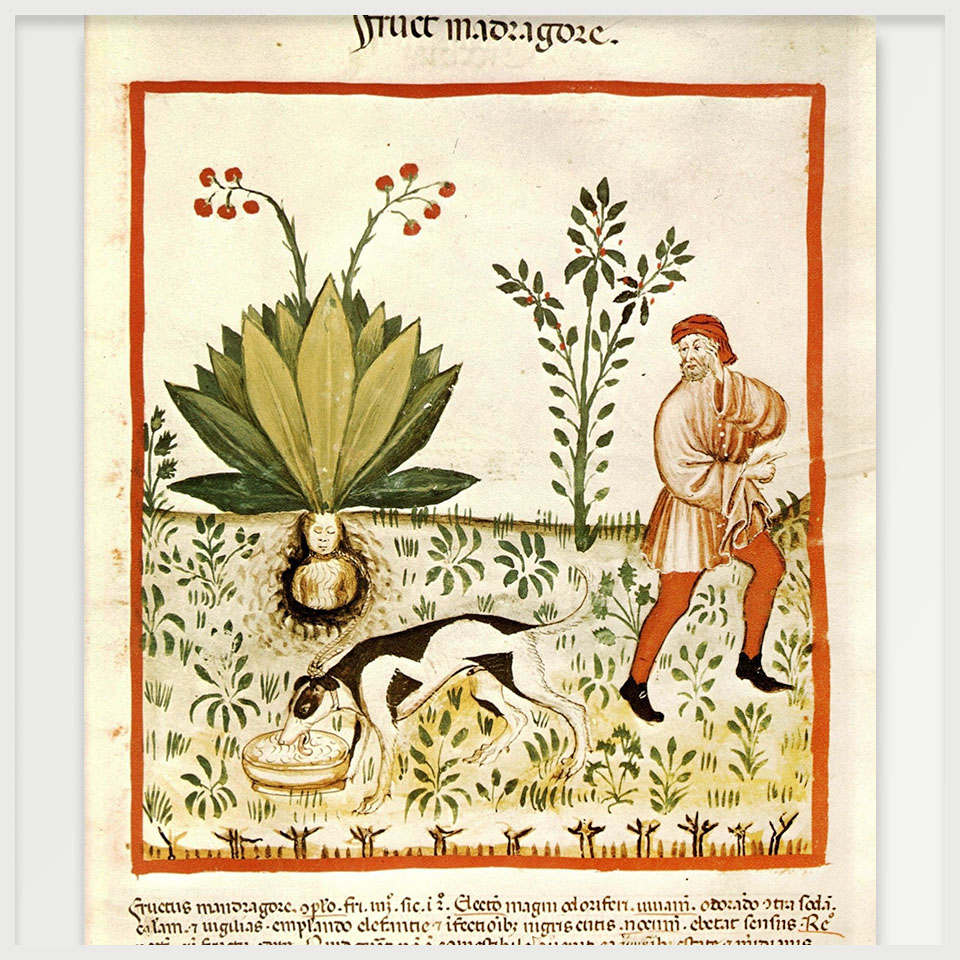

Medicina Antiqua Illustration depicting mandrake harvesting

Christianity and Paganism

In the Middle Ages there was much scorn for the Pagan worship of Goddess nature (who is synonymous with Venus or Aphrodite). This too is reflected in the medical manuscripts of the day. Consider, for example, the “editing” or erasure of an invocation to Gaia found in an early 13th century Viennese manuscript, Medicina Antiqua, by an unknown monk living sometime later in the Medieval period. The erasure in question was found on the back of an image depicting the invocation of the divine mother.

“She stands in classical clothing on the banks of a river in which the river god Neptune can be seen sitting with his trident on a snake. Mother Earth holds a cornucopia in her arms and is surrounded by stylized palms and fantasy plants.” (Müller-Ebeling: 2003, 184).

The fifty-one line invocation on the back of the image originally began “Sacred Goddess Earth, bringer of natural things…” but was changed to “To the Sacred God…” by the monk in question. In the 15th century, much of Northern Europe “fought hard for a reformation of the religious and moral foundations of spiritual life” but in sunny Renaissance Italy there was to be found an opening and renewal of the senses, a “rediscovery of classical sculptures of the gods as well as to texts that were bought from the cloisters by…Cosimo de’Medici” (Müller-Ebeling: 2003, 180).

Italian philosophers and artists of the time were concerned with understanding and exploring nature’s beauty and “the congenial side of the human character [was given much greater attention than was] the sinful” (ibid). A comparison of Germanic and Italian art of this period can be quite revealing; the former tradition is full of images of infernal hells (e.g. Hieronymus Bosch), the latter dedicated to an exploration of anatomy and perspective rooted in a renewed pagan grace (e.g. Leonardo, Raphael, Michelangelo). For confirmation of this claim, one can for example study the encoded pagan symbolism present in Michelangelo’s anatomical drawings.

Pictured: 17th Century Bible

Given the church’s disdain for nature worship and resurgent pagan sensibilities, it is no wonder that Giordano Bruno, the Renaissance magi who considered medicine to be a branch of natural magic, was eventually burned at the stake for heresy (in particular, he was put to death for his belief in an infinite number of worlds). In his treatise De Magia Bruno provides a list of ten definitions of the words magic and magician. The one that especially interests us reads as follows: “Magician: someone who does wondrous things merely by manipulating active and passive powers, as occurs in chemistry, medicine and such fields; this is commonly called ‘natural magic’” (Bruno: 1998). For Bruno, the natural world and the divine world reflected and interpenetrated each other. To use and to understand herbs was to know, in the sense of gnosis, the action of divinity in nature; it was also to realize that through the work of learning to read the book of nature that one in turn serves to illuminate the divine:

“… for as the divinity descends in a certain manner inasmuch as it communicates itself to nature, so there is an ascent made to the divinity by nature, and so through the light which shines in natural things one mounts upward to the life which presides over them” (Bruno quoted in Yates: 1940, 183).

Bruno also gives us an insight into the common practice of using incantations and physical traces left behind by or belonging to a person to affect a cure or to set a curse in motion:

“Wicked or poisonous magic: incantations are associated with a person’s physical parts in any sense; garments, excrement, remnants, footprints and anything which is believed to have made some contact with the person. In that case, and if they are used to untie, fasten, or weaken, then this constitutes the type of magic called ‘wicked’, if it leads to evil. If it leads to good, it is to be counted among the medicines belonging to a certain method and type of medical practice. If it leads to final destruction and death, then it is called ‘poisonous magic’ (Bruno: 1998).”

Hellebore and Mandrake

Not all figures of the Italian renaissance shared the magical and animistic views of Bruno, and the more “rational” voices of the time thought that Bruno and his ilk were quite mad. But even among the more conservative authors, herbal medicine was still widely referenced and bound up with mythological associations. The famous poet Torquato Tasso took issue with Bruno’s worldview and in discussing his work quoted Erasmus’ phrase “Anticyram navigat”, literally ‘set sail for Anticyra’. Anticyra was a place that was known to contain an abundance of the herb hellebore (Veratrum album), then used as a cure for madness (Yates: 1940, 191)). Let us turn to consider this herb, and the related mandrake (Mandragora officinarum), both of which can serve to give us some insights into the practices and belief systems that existed in the Italian herbal tradition, especially the tradition maintained by the rhizotomes, or root diggers, the magician-herbalists of the ancient world.

Hellebore (Veratrum album, white hellebore, veratro bianco in Italian); Helleborus niger, black hellebore) was a very important herb not only in ancient and renaissance Italy but also in Greece, France, and Egypt, among other places. Theophrastus maintained that the two types of hellebore were the most important medicinal plants that were used in ancient Greece and Rome. Contemporary ethnobotanist Christian Rätsch says of the hellebores: “they were the central medicines of the rhizotomes, diggers who nourished the magical plants with shamanic rituals. Hellebore was a sacred plant of the gods” (Rätsch: 2005, 525). Rätsch speculates that name helleboros is derived from hella-bora, which means “food of Helle.” The Hellespont is named after Helle who fell into this body of water after narrowly escaping death. Helle’s stepmother Ino resentfully roasted all of the seeds in the region of Boeotia so that a massive famine would result; this famine she blamed on Helle and her brother Phrixus, the stepchildren she so hated, in a ploy to have them killed. However, a flying golden ram sent by their birth mother Nephele saved these two. Helle fell from the ram into the Hellespont, where she was saved by Poseidon and metamorphosed into a goddess of the sea (in some less interesting accounts of the myth Helle simply drowned).

Rätsch argues that the most important documented use of this herb involved turning the root into a snuff. This is because “the artificially induced sneezing (the German name nieswurz means “sneezing root”) was believed to cause the demons of sickness to leave the body” (ibid). The Greeks and the Romans used the white hellebore1, which was ritually harvested in a way similar to the mandrake (Mandragora officinarum). Pliny gives a detailed account of the uses of white hellebore, which also gives us insight into the nature of medical treatment in the Rome of his time:

The body must be prepared beforehand for seven days by spiced food and abstention from wine, on the fourth and third day through vomiting, on the day preceding through fasting. White hellebore is also given in something sweet but is best in lentils or in a mush… The emptying begins after about four hours; the entire treatment is over in seven hours. In this manner, white hellebore heals epilepsy, …dizziness, melancholy, insanity, possession, white elephantiasis, leprosy, tetanus, tremors, foot gout, dropsy, incipient tympanic water, stomach weakness, charley horse, hip pains, four-day fever, if this will not disappear in any other way, persistent coughing, flatulence, and recurrent stomachaches (Pliny quoted in Rätsch: 2005, 527).

Consideration of the harvesting rituals common to hellebore and mandrake can give us interesting insights into the practices and beliefs of the rhizotomes as they engaged their art in Greek and Italian herbal traditions. The harvesting of these two plants involved many preliminaries and precautions. “Naturally a weird story of perils incurred in obtaining a plant strengthened belief in its magic powers and added to its commercial value” (Randolph, 489). Theophrastus describes the practices of the root diggers in his History of Plants, with specific reference to the mandrake: “Around the mandragora one must make three circles with a sword, and dig looking toward the west. Another person must dance about in a circle and pronounce a great many aphrodisiac formulas” (Theophrastus quoted in Randolph: 1905, 489). He also mentions the necessity of standing with one’s back to the wind so as not to be exposed to strong odours that some plants may emit, and anointing any skin not covered by clothing as a means of protection and defense. Other practices involved the “digging of certain plants only by night, [and] avoiding the sight of certain birds” (Randolph: 1905, 489). There were variations on these practices that depended on the plant being harvested and the uses for which it was intended. While the mandrake was to be dug up with one’s back facing west, hellebore was to be dug with one’s back facing east. Theophrastus notes that the practice of repeating aphrodisiac formulas as part of the harvesting of mandragora shows great similarities to the practice of repeating curses when sowing cumin seeds (Randolph: 1905, 490).

Mandrake Harvesting Illustrated in the Tacuinum Sanitatis manuscript, 1390

Pliny borrowed a great deal from Theophrastus and the account found in his Natural History of the practices of the root diggers and the harvesting of the mandrake in particular is one indication of this: “Those who are about to dig mandragora avoid a wind blowing in their faces; first they make three circles with a sword, and then dig looking toward the west” (Pliny quoted in Randolph: 1905, 490). We can notice however that Pliny says nothing of the “great many aphrodisiac formulas” that Theophrastus mentions in his account of the practices of the rhizotomes. Randolph suggests that “the omission by Pliny of any reference to aphrodisiac formulas is easily explained by his declaration that he will say nothing in his work about aphrodisiacs or magic spells except what may be necessary to refute belief in their efficacy” (Randolph: 1905, 490). This stance again speaks to the differences that existed in the ancient world between those who subscribed to the views and practices of natural magic and those who saw such a worldview as a breed of madness that must be rejected and defeated.

Aphrodisiacs were highly valued in Mediterranean herbal traditions, and one of the greatest of all of the aphrodisiacs was the mandrake. Rätsch comments that “in ancient times, the primary ritual significance of the mandrake was in erotic cults” (Rätsch: 2005, 348). However, only poor quality source material describing this usage remains and so detailed information about these practices is not available to us. Apart from its uses as an aphrodisiac, the mandrake was also widely used in medicine. Dioscorides:

A juice is prepared from the cortex of the bark by crushing this while fresh and pressing this; it must then be placed in the sun and stored in an earthen vessel after it has thickened. The juice of the apples is prepared in a similar manner, but this yields a less potent juice. The cortex of the root that is pulled off all the way around is put on a string and hung up to store. Some boil the roots with wine until only a third part remains, clarify this and then put it away, so that they may use a cup of this for sleeplessness and immoderate pain, and also to induce lack of sensation in those who need to be cut or burned themselves. The juice, drunk in a weight of two obols with honey mead, brings up the mucus and the black bile like hellebore; the consumption of more will take life away (Dioscorides quoted in Rätsch: 2005, 348).

The root diggers would only dig up the mandrake on the “day of Venus”, Venus of course being the Goddess of Love, which further suggests that one of the greatest virtues attributed to the mandrake in the ancient world was as an aphrodisiac, an agent in love magic/erotic rites (Randolph: 1905, 494). The mandrake is well known for its anthropomorphic appearance, and it is common in herbal traditions from around the world to attribute special healing powers to plants that resemble the human form (one can also think of the enormous sums that are paid in China even today for ginseng roots which look like human beings). Dioscorides and Pliny both make reference to a “male” and a “female” species of the mandrake but as Randolph clarifies “these terms, which the ancients applied to many plants, have nothing to do with sex, but signify more robust species (i.e., those having larger leaves, roots, etc., and attaining a greater height) and their opposites” (ibid).

The Goddess Circe

As we can see, herbal medicine in ancient and renaissance Italy, and throughout the Mediterranean region as a whole, was indissociably bound up with the workings of the gods and nature spirits. The Goddess Circe possessed a tremendous knowledge of herbs and, in particular, was regarded as a master of poisons (pharmaka). Her most famous plant was called Moly. To this plant were attributed psychoactive and aphrodisiac properties. Dioscorides referred to the mandrake as circeon, Mandragora Circaea being the herb that Circe used to transform Odysseus’ boat crew into “pigs.” (Müller-Ebeling et al. interpret this scene not in a literal sense but as an erotic transformation. The authors quote Apollonius: on the island of Circe “beasts, not resembling the beasts of the wild, nor yet like men in body, but with a medley of limbs went in a throng…such creatures, compacted of various limbs, did earth herself produce from the primeval slime…in such wise these monsters shapeless of form followed Circe” (Apollonius quoted in Müller-Ebeling: 2003, 117)). 19th and 20th century interpreters of the ancient literature (such as Dierbach and Kreuter) also take the Moly of Circe to be the mandrake. Theophrastus claimed that Circe lived in Lazio, a region in west-central Italy, where “the special medicinal herbs” were produced (Theophrastus quoted in Müller-Ebeling: 2003, 116). The sacred mountain of Circe, Monte Cicero, can still be visited today, on the Italian coast above Sicily. The early poet Aeschylus, according to Pliny, “declared that Italy abounds with potent herbs, and may have said the same of Circeii where she [i.e. Circe] lived. Strong confirmatory evidence exists even today in the fact that the Marsi, a tribe descended from Circe’s sons, are well-known snake-charmers” (Pliny quoted in Müller-Ebeling: 2003, 116).

Circe, goddess of death and guide of souls, was worshipped in groves. Apollonius notes that Circe’s groves, where executions were carried out, were lined with willows (Salix alba) and osiers/tamarisks (Tamarix spp.). Tamarisks and willows are well known medicinal trees. “The willow, or, more precisely, the white willow, was used for birth control; thus it was a typical witches’ plant” (Müller-Ebeling, 117). Two other plants sacred to Circe are the alder (most probably Alnus glutinosa) and juniper (Juniperus communis or Odorata cedrus, as it is recorded in Virgil’s Aeneid). Concerning the alder tree, it was said to surround Circe’s island (Aeaea or Eëa), located just south of Rome. Müller-Ebeling et al. comment:

“We can assume that there had been an archaic alder cult that by the Hellenic times had already been suppressed. Alders were considered transformed sisters of Phaeton, the son of Helios and brother of Circe” (Müller-Ebeling: 2003, 117). Juniper was Circe’s sacred incense and “therewith it is in the vicinity of archaic shamanism. Juniper is one of the oldest incense materials of the Eurasian shamans” (ibid).

Let us conclude our discussion of Circe by noting that though she has been described as compassionless and called the mother of darkness and horror, this noble sorceress was originally worshiped as a healing Goddess. As Giordano Bruno writes:

Ah, if only it pleased the sky, that for us today, like once long ago in happier centuries, this ever magical Circe would appear, who would be able to put an end to things with plants, minerals, poisons, and the magic of nature. I am certain, that despite her pride she was merciful with regards to our misery (Bruno: 1998).

Diana (Artemis) and Pan. Engraving after Annibale Carracci

What We Can Learn From This Symbiosis

To conclude, let us illustrate with another example just how bound up the practices of the healing arts were with the pagan pantheon of Gods and Goddesses – and consider how we can still learn from these sources of inspiration from the mythological imagination of the Renaissance. Consider Artemis/Diana, a woodland Goddess who served as the archetypal herbal healer throughout antiquity. She has very close ties to the animals of the forest, and oversees the wild hunt. Artemis is the goddess of the moon, the fierce protectress of the wild and of all of the life which courses through it, and it is she who governs the cycles of fertility and birth. Artemis’ garden is wild nature. Her role as a great shamanic healer is further brought to light through her representation as the “great she-bear, Ursa major, ruler of the stars and protector of the axis mundi (pole of the world) marked by the pole star at the centre of the constellation of Ursa Major” (Brooke: 1992). Artemis is closely associated with the artemisia plants, such as mugwort and wormwood (plants that help to enhance the clarity of consciousness, promote emotional resilience, and foster a refined sensitivity to and deepened awareness of our place in the world and our interactions with human and other-than-human nature). As explained in the Medicina Antiqua:

“There are three types of Artemisia. All three and their healing effects were discovered by the Goddess Diana. She transmitted this medicine chest to the centaur Chiron, who was the first to transform it into medicine. This is why these plants carry the name of Diana, or rather Artemisia” (Medicina Antiqua 13, fol. 32r).

When we read this and related sentiments, it becomes clear that without Artemis the tradition and practices of the Renaissance magi-herbalists would be inconceivable.

Healing was, in the Renaissance traditions here under discussions, associated with the qualities of grace and beauty. Artemis/Diana was said to be exceptionally beautiful, her beauty being comparable even to that of Aphrodite. Psychologist Ginette Paris suggests that Artemis sanctifies “solitude, natural and primitive living to which we may all return whenever we find it necessary to belong only to ourselves” (Paris: 1986, 124). In her capacity as a huntress and archer, she can bestow upon us the wild, atavistic power that can be utilized to resist the forces of domestication and domination. Artemis is the great protectress of flora and fauna, and thus she has a special bearing on the ecological issues that face living beings on the Earth today. It would be wise to look to her when making choices that will affect the future of the natural world.

“There are obviously many ways of entering into therapeutic contact with nature, but solitude and identification with nature through falling water, trees, or animals are cues that our contact is with Artemis rather than Dionysus, Demeter, or Aphrodite” (ibid, 127). The waters of the mountains and streams are also under the care of Diana, and if we are to re-enliven our sacred relationship to this elemental force then “perhaps, afterward, the nymphs, naiads, and nereids would return to inhabit our imagination and teach us the necessary respect for the waters of Artemis” (ibid). Let us not forget the mythological traditions of healing and the great bearing they can have on contemporary consciousness, let us take heed not to neglect the great Pagan wisdom of the wild imagination.

Bible page depicting the prophet Ezekiel’s Vision, 1648

Footnotes:

1 Daniel Schulke claims that black hellebore is “a poison of decided infamy; all parts of the plant render up potent venoms” (Schulke: 2017, 132). An extract of the rhizome was used in antiquity and into the medieval era as a “utensil of murder, most notably by King Attalus III of Pergamos” (ibid). Black hellebore contains the glycosides heleborin and hellebrin, which are chemically related to telo-cinobufagin (venom found in some species of toad skin). These glycosides slow the heart rate and affect cardiac muscle in a similar way to foxglove. The Key of Solomon the King contains a recipe for an incense to be used as part of a “spell for vivifying a talisman with the genius of Saturn” containing the stalks of black hellebore along with alum, assafoetida, scammony, sulphur, and cyprus ash (ibid).

Works Cited:

- Brooke, Elisabeth. A Woman’s Book of Herbs. London: Aeon Books, 1992.

- Bruno, Giordano. Cause, Principle and Unity: And Essays on Magic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Hillman, James. Re-Visioning Psychology. New York: Harper, 1976.

- Müller-Ebeling, Claudia, Rätsch, Christian, and Storl, Wolf. Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants. Vermont: Inner Traditions, 2003.

- Paris, Ginette. Pagan Meditations. Connecticut: Spring Publications, 1986.

- Randolph, Charles Brewster. ‘The Mandragora of the Ancients in Folk-Lore and Medicine.’ Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Vol. 40, No. 12 (Jan., 1905), pp. 487-537.

- Rätsch, Christian. The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Plants. Maine: Park Street Press, 2005.

- Schulke, Daniel. Veneficium: Magic, Witchcraft, and the Poison Path. San Francisco: Three Hands Press, 2017.

- Silberman, Henri. ‘Superstition and Medical Knowledge in an Italian Herbal.’ Pharmacy in History, Vol. 38, No. 2 (1996), pp. 87-94

- Yates, Frances. ‘The Religious Policy of Giordano Bruno.’ Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 3, No. 3/4 (Apr. – Jul., 1940), pp. 181-207.

Illustrations/Images:

- Medicina Antiqua Illustration

- 17th Century Bible: (photo provided by Serena Mor)

- Veratrum album Illustration

- Mandrake Harvesting

- Diana (Artemis) and Pan

- Prophet Ezekiel’s Vision: (photo provided by Serena Mor)

Cannabis: Medicine or Poison?

An Exploration from the Perspectives of Traditional Systems of Healing

With the legalization of cannabis in Canada, we are seeing a growing public acceptance of this herb, an enormously expanding “cannabis industry”, and a variety of claims being made about its medical efficacy and utility. There are many well-documented traditional medical uses of cannabis, going back many hundreds of years, along with a growing body of contemporary scientific evidence supporting its various medicinal virtues. Yet many of the contemporary claims made about cannabis – branded as a miracle drug – are driven by the desire to sell products or simply as means of justifying one’s indulgences and addictions. In what follows, we will explore cannabis from the perspective of traditional systems of healing and consider some of the less acknowledged and discussed adverse reactions and disturbances that result particularly from its chronic use.