An Interview with Rosemary Gladstar

This interview was conducted as part of Everything Herbal’s ‘Herbal Elders’ series. This series seeks to honour and explore the unique contributions of longstanding members of the herbal medicine community in Canada, as well as abroad.

This interview was originally conducted with Nick Faunus, Penelope Beaudrow and Victor Cirone, in May of 2021.

“Tell us about your experience as an American herbalist?”

Everything Herbal: The American perspective on herbal medicine is presumably quite different than in other parts of the world because of all of the repression that the practice has faced in the United States. Can you speak to this history, in broad terms, and tell us about your experience as an American herbalist? Talk to us about the herbal Renaissance in the 60’s and beyond…

Rosemary: I’d like to start by saying that I’m just giving my one perspective, my own first hand experience. Everybody has a perspective, of course. After WWII, and even before that in the United States, herbalism had gone deeply underground. It was still very much alive in ethnic communities, in cities, and country areas where there were ethnic communities. These communities often still had their own medicine that they may have brought with them from other countries, for instance. Definitely our Native populations were still using some herbal medicine, though by this time modern medicine had really made headway on the reservations and there wasn’t a lot traditional medical information that was being passed along. In part, this is because there weren’t very many people who were interested in learning it anymore. In the Southern part of the United States, the Appalachian region, there were very poor rural communities still using herbal remedies – mostly because it was all that they had. They simply didn’t have access to modern medicine. And as modern medicine was being introduced as “the only legitimate system of healing” more and more of these rural communities did come to adopt it. Herbalism had gone deeply underground. Many of the traditional earth sciences and nature based traditions were changing during this time. Food production, for example: our whole food chain was changed dramatically during this same period towards the chemical-industrial model that we have in place today. Even the way that the American families were living – that idea of the “intact” family was beginning to change. After WWII when there was this influx of an amazing amount of chemicals that were being adopted by our food and medical systems, herbalism just became antiquated in this country. There were very few practicing herbalists. The ones that were still living were usually older and they were very vocal about what they were doing, but they were very few and far between. And there were very few herb books – those that were written were mostly about culinary uses of herbs, how to make crafts, and things like that. But they were not addressing the medical side of herbalism.

“Around the 60’s there was a kind of a cultural revolution…”

… And out of that rose a philosophy of getting back to nature. The term ‘organic’ was actually coined in the 60s. Before that people weren’t even talking about ‘natural’ or ‘organic’ food. And so it was out of this fertile soil that the desire to start to use natural medicines emerged anew. I would say that primarily it was coming from a young, disconnected, discontented population – much like what we are seeing happen right now. It is an entirely different issue with today’s generation: they don’t have to resurrect herbalism, but there are a lot of things within themselves that they resurrecting. I was on the cutting edge of herbal renaissance of the 60’s, I was of that age, just graduating from high-school, I was restless and discontented, and I wanted to get back to the Earth. I grew up on a farm, very close to the earth. I had very early training in herbalism because of my grandmother; that is one of the things that really helped me and gave me a head start. I grew up in a very poor farming family, with 5 children. Families like my own were using natural remedies not because they were cool or because they thought they were any better – it was because that’s what they could afford and what they were familiar with. I always proudly say that in my family, with 5 children, there were only two episodes where we had to visit the doctors. Once when my older sister broke her hip, and then again when my younger sister swallowed rat poison. In those cases, the medical society was exactly what was called for.

The other thing that was helpful for me was having a grandmother who was very well versed in herbalism, I like to always clarify this was in the old sense of the word. She used herbs because that is what she was trained in and knew well. She was genetically programmed to work with the plants. We see this in many different humans beings, that there is a deep calling to become involved with the plant world. We see this in different families and communities. My grandmother was certainly one of those people, and probably if I had known my lineage going further back in time I would have seen it there too, stretching back through the generations. That’s how it usually is. My grandmother was a survivor of the Armenian genocide and she use to tell us that it was her faith in God and her knowledge of the plants that saved her life. She really felt it was almost a religious duty to teach us about plants, as food primarily, but also as medicine. How that all ties in to your question is simply that going back to the Earth for me meant going way up into the mountains, learning with a lot of the elders, a lot of Native people who are very into sharing their knowledge with non-Native people because most of the younger generation were not interested at that time in learning. What we found a lot with older people in different cultures around the world was that they were eager to share this knowledge and information with anybody who was called to hear it. Those were my earliest teachers: my grandmother and the elders that I met. They weren’t all elders; there were certainly younger people who were sharing knowledge and information freely with each other, too.

“I was spending a lot of time backpacking, spending time with the plants.”

In 1972 I opened my first herb store in Northern California. There was one other herb store in San Francisco owned by a wonderful elderly couple, it was a landmark. Eventually a third store opened in Southern California. These little herb stores became focal points for large communities to get their plants. There were other herbalists doing this by the way, pocketed in different areas throughout the country. The herb stores were one of the early ways of spreading knowledge, people in the stores weren’t just selling herbs, but also teaching and educating, helping and healing. At that time we were doing all of that very freely – the stores were more like clinics of a sort. Then what happened was around 1974, right after I opened my herb store I started hosting classes. I didn’t know very much, I was in my early 20’s, how much could I really have known? But what I did know was more than anybody else, so I just shared more than I taught in a formal sense.

Shortly after that, I started hosting herb conferences and this was very pivotal. They were actually quite large even from the beginning. The very first one was at Rainbow Ranch in Sedona County, 1974. 50 people came to that weekend, admission was $25, there was food and lodging and dancing and music, much like the events we see today, which are patterned after that first one. We started holding those seasonally, 4 times a year during the solstices and equinoxes. Those events just catalyzed herbalism in the United States. Many people were learning and became teachers; the conferences helped to create seed balls of herbalists that you just tossed out into the wind. We didn’t have really well known teachers at that time, but one of the things that we did do that I thought was always very progressive was that we invited whatever elders we could find that would come and share with us. We had people like Rolling Thunder, Sun Bear, Wallace Black Elk, Norma Myers, Juliette De Bairacli Levy, Dr. Christopher… Our desire was to host these elders who were the treasure keepers of herbal knowledge, carrying it forward at a time when it wasn’t popular, there wasn’t money to be made or anything like that. Somehow or other we knew how to recognize these people, who seeded us, inspired us. We were the children of that time, learning at the feet of these great masters. It was really so grassroots, all underground, that was the beauty of it because what was coming up was from the plants themselves. It wasn’t the white coats teaching us anything, and by that I don’t mean the medical profession – it wasn’t coming from the colleges and universities. It was very grassroots, coming from the Earth, and people absorbing this through the souls of their feet into the souls of their being.

“By the 1980’s herbalism was still pretty underground.”

There was a generosity that to me was so inspiring, there was never any “this is my knowledge, this belongs to me” – it was just what I would call a very eclectic sharing; people feeling humbled by this knowledge and proud to be able to pass it on. By the 1980’s herbalism was still pretty underground. After the conferences it was in 1984 or so that I founded the California School of Herbal Studies, which became the longest running and one of the most successful schools in the United States. It is still going on. It has always been successful from the day we’ve opened it because people were hungry for the knowledge. It was a combination of research and scientific information but definitely based on the heart and soul of plants. At that time almost all of the students and participants who would come to these events were younger people, they all had lots of hair and not much clothing! That was always my joke. Wonderful radical earth based people.

In the mid and late 1980’s we began to see herbalism spreading like a mycelial network – right around that time immune disorders became a major issue, we had the AIDS epidemic and that just skyrocketed the awareness and information about the immune system and immune damage. Echinacea – who I always call the great herbal diplomat – rose up. Even though part of American herbalism, Echinacea hadn’t been used very much apart from within the Native traditions. It was being shipped in massive amounts to European markets, but was not being used in the United States. Here is the beautiful purple coneflower that people were growing in their backyard and recognized; all of a sudden it was being used for the immune system – people used it and saw that it works. It was the first herb that made the headlines. It was beautiful and familiar; people could find it at their garden centers. Then the industry began to grow – we started seeing the herbal industry, which went from pretty much nothing to an enormous global marketplace. This brought with it wonderful success for many herbalists, but it also came with its own set of issues and problems.

United Plant Savers

Around the early 1990’s we first began to address these issues around industry, with herbalism becoming very popular and acceptable again. In 1994 we formed a small organization that has become national and is now spreading internationally, called The United Plant Savers. It was formed completely as an organization that could serve as a voice for the plants; instead of asking what the plants could do for us, we sought to ask what we could do to give back to the plants. That organization marked a real shift in American herbalism; we felt like we had really matured. We had been using plants, teaching about them, spreading the news about them, ‘we’ meaning hundreds and thousands of people at this point, all doing our assigned work here on the Earth. We had matured enough to realize that the plants were sacred medicine, very special medicine, and that we had a responsibility as plant lovers to give back. For myself, during the next 10 or 15 years that became my major work, I focused less on community herbalism, which I’ve always done, less on my work as a teacher spreading information on how we can use herbs, and spent a great deal of my effort, energy and resources on really trying to turn our focus to what we could do to give back to the plants and the earth.

Fire Cider

Everything Herbal: The traditional herbal tonic Fire Cider has been a big issue in American herbalism in recent years, can you tell us about that story?

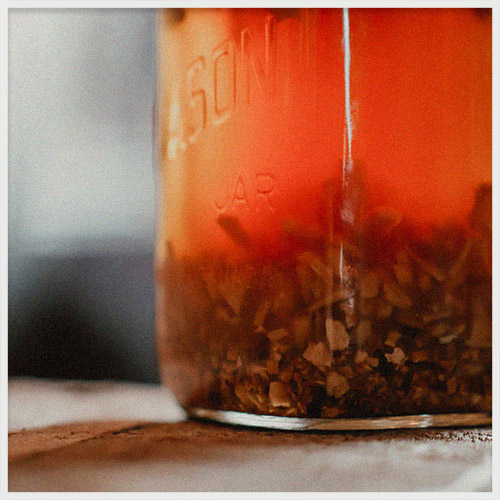

Rosemary: Fire Cider became another enormous issue amongst herbalists because up until this time, about 6 or 7 years ago when this all happened, herbalists had been very freely sharing recipes, oftentimes not claiming them as their own. Of course if you had a company or a business you often had to trademark your products because you were investing a lot of money in them, but within the larger community there were these traditional remedies that had been exchanged and traded, sometimes for centuries – like Four Thieves vinegar, for instance. Some recipes had been freely shared for decades, like Fire Cider. I had created the Fire Cider formula in the herb school with a bunch of students; it was a very creative process. I was teaching my students, we were making a product that had a very clear intention and we put together this formula that would be low cost, something that anybody could make, whether you are an herbalist or not. Fire Cider is something that you could go to the grocery store and collect the ingredients for and simply make in your kitchen. It is thought up as an easy and accessible tonic for the immune system, something to help ward off flus and colds. This formula I taught the first time in 1979 or 1980 at the California School of Herbal Studies. I printed it because I thought it was a great and useful recipe, it wasn’t any greater than a lot of the other recipes that I made, but it was one of those that became very well known. And it has just travelled out on its own the way that recipes should. My students taught other people, people started adapting it and making it their own, which is exactly what was supposed to happen. In truth most herbalists know that we don’t create anything, we are just vehicles, things come through us, we are building on our ancestors. I might have read that recipe in some ancient book and forgot about it. That is how long this information has been here. But nonetheless, everything was pretty happy, Fire Cider was part of this traditional collection of recipes that were considered to be collectively owned by the herbal community until a company – Shire City – came along. Now this was a young startup company who admitted that they were not herbalists and didn’t know anything about herbs. They had come across this recipe and they made it, thought it was great and shared it with friends, just like everybody had been doing for a little over 3 decades at this point. They started selling it at little craft fairs and started making money from it and they thought ‘aha! we are going to trademark this!’ And that is what they did, without telling a soul. The way that trademarks are set up in the United States is that you have a 6 month period to contest any new trademarks, but this company did not let anybody know that they had trademarked Fire Cider until after that window had closed. Then they started sending letters, very nicely written letters, to all the small companies who had been making Fire Cider and selling it saying ‘oh so sorry we have trademarked Fire Cider, it’s our recipe now and you are going to have to stop selling it.’

They were dealing with herbalists and they didn’t realize that herbalists are, by our nature, on the outside, on the fringes. We have had to learn to fight for what we believe in. There were times many years ago when herbalists were burnt alive for practicing. During the European inquisition, millions people were classified and persecuted as witches and part of what they did was practice the healing arts. Herbalists have stood up for what they believed in for centuries and we have been practicing a medicine that is illegal in the United States, so we were not just going to roll over. The herbalists Nicole Telkes, Mary Blue, and Kathy Langelier (now known as the Fire Cider Three) along with a group of others, decided that we were not just going to allow this to happen. If Fire Cider was allowed to be trademarked, any of the other traditional products that had been around for 10, 15, 200, 500, 5000 years could also be trademarked. What that would mean is that they would no longer be available for herbalists to make or sell. That just seemed totally wrong to us. It wasn’t a fight against trademark, it was a fight against trademarking traditional collectively owned recipes.

“We were forced to take a big stand”

The company turned around and sued these 3 women. We are not really sure why they didn’t include me in the lawsuit. For one thing, I hadn’t sold fire cider for 35 years, though I used to sell it in my herb store. I stood up for those women, and so did the entire herbal community. We all joined forces and insisted that this is not going to happen, you can’t take our traditional recipes away from us. You can make your own recipes, add something different or come up with your own product names, we wish you all the success in the world, but you can’t try to disrupt our traditions. This case ended up going to federal court, we spent 9 days in court fighting for traditions not trademarks and we won, thanks to our really good lawyers who donated their time to our cause. We are talking 5 full years that this lawsuit went on for. It was difficult and really challenging. There were lots of times when we were just worn out from it, it required lots of money, we all pitched in and helped to pay for it, and so did the whole herbal community.

“The community really rallied to support us.”

We felt that even if we didn’t win the case we won anyways because we stood up, that to me is the thing we always had to keep in mind: just by standing up we had taken a stand for what we believed in. When we did win it was an enormous accomplishment for the entire herbal community. This case was called a landmark case, a precedent setting case. Our victor not only meant that herbalists were protected but also that if you are an artist or some other craftsperson and within your craft there is a well-known product, somebody can’t just come along and trademark it. It doesn’t have to be something that is broadly known and recognized by the general public, as in our case herbalists are considered a subgroup of the population. Shire City argued in their defense that Fire Cider was only popular amongst a small group of people, and so it was fair game. The case was won based on the fact that even though we were a small subgroup of people, Fire Cider was well known in our community and so was to be kept free from trademark restrictions. In other words, this case not only meant that herbalists are now afforded better protection – it doesn’t mean that companies won’t come along and try to do this kind of thing again – but now we always have a case that we can refer to if such a thing does happen in the future. We are proud of ourselves for that, and also really glad that it is over!

“What are your feelings about the way the herbal industry has shifted?”

Everything Herbal: Your actual battle was against the misuse of the trademark laws by a company that saw a profit making opportunity, which leads to another question: we have watched the herbal industry develop in the same way. I started my business [Faunus Herbs] growing Echinacea. The thing we see today is the institutionalization of herbalism, herbalism becoming part of mainstream culture. In Canada we see it being taken away from us and being given over to a group of people with no grass roots skills, no nothing: bureaucrats who are keen on monitoring and controlling things. And in the United States things are going the same way, things are being institutionalized and monetized. In Canada for instance you can’t even make a claim about a plant without being threatened with jail time. This is something you’ve been able to do for thousands of years, and it has now been taken away from us. What are your feelings about the way the herbal industry has shifted? It is great that herbs are now available everywhere, but there have been so many restrictions placed upon us. Our herbal formulas are works of art, analogous to blues tunes. One you record a blues tune, it becomes stuck forever, with the same notes, the same everything. But that is not what it is in essence. How do we guard against this rigidity coming into the sphere of our herbal knowledge?

Rosemary: We have been fighting this battle for a long time. In the 1980s we had a wonderful herbal organization called the American Herbalists Guild come into being. It is a professional organization and they were founded on the basis that they wanted to create standards for herbalists. They had really good reasoning: we need to set the standards before the government does. The larger herbal community said no, we don’t even want a group of herbalists to create those standards for us, because so long as we stay united in this fight we will eventually win. If we have a small group of herbalists who feel that their vision is the one to go on, then we stat to create divisions and hierarchies in our community. The intentions of these people who wanted to set standards for herbalism were incredible and some of the people who were behind this movement were brilliant practitioners and close friends of mine, but there was another group of us who just argued that we don’t want to do that, we don’t want another group of herbalists who say this is our recognized and acceptable course material, etc. We can see what happens with that: when you look at any institution that has allowed those officially sanctioned standards to dominate, they don’t end up serving the people. In our case, such standards would not serve the plants or the herbalists in the long run. Eventually after many years of dissension the AHG became more supportive of this other way, partly because there were a lot of young herbalists that became involved in the organization.

We have a small organization in America called The National Health Freedom Movement. I have been really educating people about this group and inviting their members to be keynote speakers at our conferences. This organization is comprised of lawyers who go state-by-state changing the laws, advocating for greater health freedom rights. You and I as citizens of a free country should have the right to chose the type of medicine we take and the practitioners that we consult with. Within these laws, called safe harbor exemption laws, are clauses that protect practitioners of non-licensed healing arts. So far in the United States we have 18 states that have passed these laws. I was on the board of directors of this organization for a time, but had to step down because of events in my personal life. Now my main way of spreading this news amongst herbalists is by inviting Diane Miller, a very powerful speaker, to be a keynote at our conferences. It is so important that this information about health freedoms and personal health choices gets out there. We as herbalists don’t need to get legalized by the government, we need laws put in place to provide us with freedoms and protections. These laws demand that we have integrity in our practice by, for example, always clearly stating where we have studied and for how long. This is important. Me, who has never had any formal training, I would just say I studied with my grandmother, founded my own school, and have been practicing for so many years, but don’t have any official credentials. And anybody who felt safe coming to see me would have the right to do so.

The other thing that these laws demand is that you don’t practice outside of the realm or scope of your profession. As an herbalist with very little medical training I won’t use medical terminology or medical diagnostic skills. These laws protect unlicensed practitioners. I am an enormous advocate of these laws, which have become very active right now because of COVID. The National Health Freedom Movement is a more radical group who feels that you should not have anything forced on you with regards to your personal health. Their big stand is health freedom rights for individuals. It is important that we have some form of protection just being herbalists, with or without certificates. It is dangerous when a government body starts telling us: this is how you have to be in order to be a practicing herbalist. I do think that medical standards can be good. There are some people for whom they are necessary, they just feel more comfortable with an herbalist who has medical training or who is accredited. I just think that as free citizens we need to maintain our freedom of choice.

When it comes to your own healthcare and that of your family, it is your right and not the government’s to step in and decide these things for you. People are today forgetting that, they are willing to let the government decide what you are going to eat, what you are going to put into your body, the kind of medicine you are going to use. Benjamin Rush, a doctor who signed the Declaration of Independence, said if we allow the government to decide what medicine we use, we will become a despotic nation. Thomas Jefferson made a very similar statement: the people have a right to choose what food and medicine they use. We have to be mindful; these kinds of regulations often come with good intentions. When the doctors got together in the mid 1800s with the aim of forming a medical association and setting certain standards, they ended up shutting down the Eclectic schools of medicine [a branch of American medicine which made extensive use of botanical remedies], which were some of the best medical schools we ever had in this country. By the 1940s, the last Eclectic school had been closed. These state licensed doctors went on to become the one and only medical system in America – and look at what has happened to medicine in this county, and beyond. Of course it is incredible and wonderful in some ways, but the way that it is set up doesn’t serve everybody, and is not well suited to all health conditions. It has become despotic in many respects.

We have spread this grassroots movement so strongly in the United States and I believe in Canada as well. In the United States I know that there are many thousands of us, community herbalists practicing out of our own homes and there is no way anyone is going to squelch that movement. Grassroots are very strong, they may go underground for a while, but herbs grow really well underground, the roots grow and spread well. You keep preaching and teaching and spreading that information and there is no way that it will ever be squelched again.

It is important to reiterate that this is just my view of American herbalism, we are a strong and very eclectic group and every person you ask will have a different story. I was there when it started mushrooming, and it was a very lively and exciting time. I’m grateful.

To learn more about Rosemary and her work, visit her online at: www.scienceandartofherbalism.com

–

Photos provided by both Rosemary Gladstar and Serena Mor